So I got put on the robes again! Doubly officially a Dr of Philosophy now!

In 1967 Stanley Fish published a seminal work that reconceptualised the understanding of John Milton’s Paradise Lost. In Seduced by Sin Fish argued that the true subject of Paradise Lost was not Satan, or Adam and Eve, but the reader himself who, through the epic poem’s structure and use of recognisable narrative forms (Satan’s heroic journey being patterned on The Odyssey and The Aeneid), experiences his own fall. For Fish the reader is “confronted with evidence of his corruption” (1967, ixxii) when he realises his seduction by Satan’s heroic narrative and should, by the end of the work, come to realise his own temptations and spiritual limitations, becoming a sort of guilty reader who develops an understanding of the limits of his own spirituality.

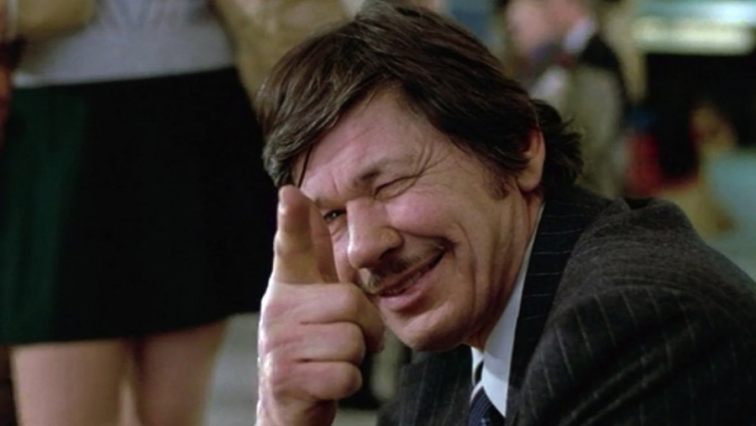

At first glance a 17th Century English poetic work seems to have little in common with Death Wish, a film that has long been neglected by serious critics despite its box-office success and evident influence on cinema (arguably starting a whole sub-genre of vigilante/revenge films which continues to this day, with a 2018 re-make). Indeed Death Wish was received with outright hostility by most main-stream critics in the US and UK, and still exists as a sort of by-word for violent exploitative film – happily referenced during real-life crimes, such as those of Bernie Goetz in 1984, by lazy journalists.

On its release Vincent Canby, in The New York Times, called it

a despicable movie, one that raises complex questions in order to offer bigoted, frivolous, oversimplified answers

in July 1974, returning in August to decry its popularity with “law-and-order fanatics, sadists, muggers, club women, fathers, older sisters, masochists, policemen, politicians, and, it seems, a number of film critics”. Roger Ebert denounced it as “propaganda for private gun ownership and a call to vigilante justice”, and Richard Schickel called it “vicious”. Judy Klemersud was sent by The New York Times to answer the question “What do They See in ‘Death Wish’?”, noticing how audiences cheered when Bronson (as the audience identified him, not his character Paul Kersey) gunned down muggers, and confessing that she too found herself, much to her shame, “applauding several times.” A clear characterisation of the film and its audience emerged, but if it was intended to warn away movie-goers it failed as the film took over £20 million in the US on a budget of $3million (Talbot 2006, 8).

But what if there’s something more complex at work in Death Wish? What if we can take Fish’s ideas about the reader in Paradise Lost and apply them to a film written off as exploitation? What emerges is a film much more complicated than previously assumed – one that tempts the spectator into identification with a psychotic protagonist, forcing them to reflect on their own sense of law, order and justice and the lure of simplistic answers to complicated problems.

Use of Myth & Genre

Many critics have perceived Death Wish as a sort of “urban Western”, an attempt to relocate the form to a more relevant setting, taking account of the demythologising of the genre that occurred through the 1960s and the early 1970s (through the Spaghetti Westerns and revisionist films such as Little Big Man (Arthur Penn, 1970)). There is much on the surface that makes this suggestion appealing; Death Wish repeatedly references the codes of law and order represented in the Western, most notably in Paul Kersey’s journey to Tucson where his is schooled in “the old American tradition of self-defence” by Aimes Jainchill, the sort of man who carries a gun openly and has bull horns on his car. The casting of Bronson as Kersey, who came to fame in The Magnificent Seven (John Sturges, 1960) and cemented his association with the genre in Once Upon a Time in the West (Sergio Leone, 1968), furthers this, lending the theory some pertinence which is helped by the film’s direction.

Winner directs the film in a traditional Hollywood style (despite his English nationality), eschewing the experiments of form that characterise the New Hollywood period when the film was produced. Indeed one could quite happily label his work as heavy handed, if efficient in covering ground quickly. Generally speaking, except in the infamous rape scene, Winner avoids using subjective techniques, instead allowing the spectator to remain distanced from the action, watching it unfold rather than being in the centre of it. This lends the film a sort of comfort in its spectating position, as does the use of genre tropes from the Western, helping to put the spectator at their ease.

When Kersey’s wife and daughter are attacked the attacker’s behaviour can easily be compared to that of the “Red Indians” in any of the multitude of Westerns audiences had familiarised themselves with through film and television during the past decades.

Much of the initial critical opprobrium directed at the film stemmed from the rape scene and Winner directs it to cause maximum offence and impact – the effect of this is two-fold. First it brings to life the implicit rape threat that was contained in many Westerns for a modern audience more accustomed to such images by films such as A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971) and Straw Dogs (Sam Peckinpah, 1971), but also it’s critical for the rest of the film that the crime be sufficiently disturbing that Kersey’s reaction to it seems, on the surface at least, reasonable. From this Kersey’s rediscovery of a Western code of justice follows, with the crime fitting that code – it is after all his “women-folk” who have been attacked in his urban “home-stead” (his wife is killed, the daughter is left in a vegetative state, conveniently unable to voice her own views).

Underpinning the Western genre is a binary opposition between the Wilderness and Civilization, the former a male environment in which the hero belonged, versus the feminizing force of the latter and Death Wish plays with this suggesting that the feminising power of civilization has left Kersey unable to protect his family, and the authorities impotent in the face of crime. Such a philosophy is espoused by Jainchill during the Tuscon segment, where the wide open spaces are contrasted to the dark alleys of New York. Here Kersey witnesses a Wild West show, an artificial and corny representation that beguiles him. Here he discovers a simple answer to New York’s crime problems – the good man versus the bad man.

Generating Complicity

There is no doubting the seriousness of crime, and especially mugging, during the 1970s so one can assume a certain pre-existing sympathy on behalf of the spectator, especially as they had paid to see a film in which the advertising campaign had highlighted the controversial elements (the tag-line read “Vigilante, city style – judge, jury and executioner”). But the film goes further in seducing the audience towards being sympathetic to Kersey by surrounding his actions with supporters and suggestions that his acts would have a significant impact on crime (the DA claiming a reduction in mugging from 950 per week to 470). The representation of the media within the film, complete with Western inspired imagery such as a noose and the headline “Frontier Justice in the Streets” on the cover of Harper’s, serves to cement this. A consistent narrative of Kersey’s effectiveness is built up – so much that it inspires other New Yorkers to defend themselves (such as Alma Lee Brown, seen in a TV news report, defending herself with a hat-pin).

These elements, alongside the comforting familiarity of the Western model, invite the spectator to align more closely with Kersey as the film continues, as does the comparison provided by Kersey’s ineffectual son-in-law and the scenes in which Kersey is confronted by a police force unable to catch his wife & daughter’s attackers. Having primed us in Tuscon the film returns to New York where Kersey starts acting out his new found sense of law and order, imaging himself to be the lawman of myth.

Kersey’s first act of violence is in self-defence (using a sock filled with a roll of coins), his second (this time with the revolver given to him by Jainchill) saves a man from being mugged. These actions fit within the narrative conventions of the Western, ideas of self-defence or helping the defenceless. They may be the acts of a vigilante, but they retain a certain sympathy, especially as Kersey reacts traumatically (vomiting after the first instance).

From then on Kersey’s actions become more sinister: he begins riding the Subway miles away from home waiting for someone to attack. He cruises the parks with no intent to look for people to save, rather he deliberately makes himself a target, enticing attackers by placing himself in vulnerable positions. And he begins to enjoy it. At home he surrounds himself with the newspapers and magazines that detail his exploits, watching the news reports that validate his actions with a broad smile on his face. He has moved well beyond the desire to protect himself and, of course, he has spent no time at all searching for those who harmed his family. It’s an often neglected detail, but a key one;

Death Wish is not a film about vengeance, at least not in a direct sense. Although the attack on his wife and daughter instigates a change in how Kersey views the world, none of his subsequent acts are directed towards punishing those responsible.

To have done so would have more easily placed Kersey into a pre-existing narrative schema, recognisable from films such as The Searchers (John Ford, 1956), but the film simply elides its way past this point and takes the spectator with it. We have the justification for Kersey’s crusade, but by omitting a direct vengeance against the criminals responsible the film moves slowly away from expectations towards something more complex and troubling. By the time Kersey is shooting men in the back, about as far from the Western code as you can get, the spectator is positioned so as not to notice the departure from expectations.

Revealing the Truth

On reflection cracks in this world appear early, indeed even in the opening prologue (added by Winner, and not present in the original novel by Brian Garfield) in which Kersey and his Wife enjoy a holiday. Ostensibly included to increase the tragedy that follows and to draw a direct comparison with the Hellish New York that follows, Hawaii is represented as an Edenic space, a land of plenty. However anyone with a cursory knowledge of crime on the islands can recognise this image as a sham, the resort an artifice behind which lies high levels of violent crime and drug-use. This effectively preys on our understandings of binary oppositions, the calm pastoral idyll as opposed to the degradations of civilization – however this Eden is so obviously false, as is the world of Tucson presented later which Kersey is so beguiled by. The Wild West show, from which Kersey draws inspiration, is over the top, a tired rehash of clichés for children and tourists in which the gun shots and deaths are clearly fake. Jainchill himself is an over the top caricature. Winner gently suggests to us here that the world that Kersey identifies with is a sham in itself; what values can possibly be drawn from it?

Alone in the film, as a voice of reason, is Detective Ochoa (Vincent Gardenia) edging towards the only logical conclusion about Paul Kersey: that he has become a serial killer. Ochoa provides an alternative protagonist in the film, but he is drawn to be uninspiring, a man of stubby cigars and crumpled coat, stuck with a permanent cold, as if crime was a literal disease. In a different edit of the film one could imagine Ochoa becoming the hero, tracking down Kersey the killer, but this would remove the growing moral complexity from the film, cemented when Ochoa tells Kersey to leave New York.

What of Kersey at this point? He has descended into a psychotic state, believing himself to be a lawman in the Old West; of course his targets aren’t the Native Americans of the films, or the bad men in black hats, but young urban men whose lives can only be hinted at.

During the final confrontation the young black man Kersey has chased and cornered can only be confused by the demand to “Draw” and “Fill your hand” – codes utterly inaccessible and irrelevant to someone who had previously exhorted Kersey to “Come on down, Mother Fucker”.

When confronted by Ochoa Kersey inquires if he has to leave town “by sundown?” Slowly, but inexorably, through the film, Kersey has bought into his own fantasies of law and order, coming to see himself as the hero of the West, but moving on to being someone who cannot distinguish between reality and fantasy.

Gotcha!

During the final moments of Death Wish Paul Kersey arrives in Chicago and, having disembarked from his train, is confronted by the sight of a gang of young men harassing a woman. As Kersey helps the woman recover the belongings that have been scattered over the floor he turns to the young men and forms his fingers into a gun shape, smiling broadly. But look at that shot again and you can see that the finger, ostensibly aimed at the young men, is pointing straight at us. It’s an image that reaches all the way back to 1903 and the first Western, Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery, which, as the legend goes, had the audience ducking under their seats with its final image of a bandit shooting straight towards the camera. The image has been remade, but the implication is the same – you’re next. The modern audience of course considers itself too sophisticated to duck their heads at such an image, but have they been too sophisticated to be seduced by Death Wish?

Through its use of familiar tropes and structures Death Wish plays out a tempting fantasy, one of easy answers to complicated questions. But rather than simply endorse Paul Kersey the film turns to the spectator and asks whether they too have been drawn in to this fantasy – a fantasy in which complex problems of urban degradation are made into narratives of good men versus bad men. The subtle hints that pepper the narrative, undermining its representations, point to a question for the spectator – are they too to be seduced like the Kersey’s many supporters in the city? As he turns to the camera in the final seconds Bronson reveals the film’s trick – a gothca moment designed to entrap us.

Just as Fish suggests regards Paradise Lost, the real subject of Death Wish is the audience. The question it asks them: are you conscious enough to see your own temptations?

Works Cited

Ebert, Roger (1974) Death Wish. Chicago Sun Times. [online] http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/death-wish-1974 [accessed 10 September 2017]

Fish, Stanley (1967) Seduced by Sin: The Reader in Paradise Lost. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Gilliat, Penelope (1974) Death Wish. New Yorker Magazine. 26 August.

Klemersrud, Judy (1974) What do They See in Death Wish? The New York Times. 01 September.

Schickel, Richard (1974) Mug Shooting. Time. 19 August.

Talbot, Paul (2006) Bronson’s Loose! The Making of the Death Wish Films. Lincoln: iUniverse

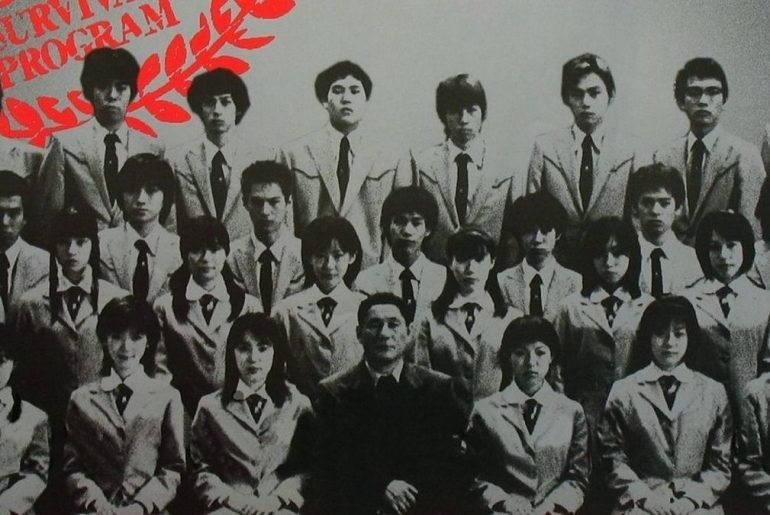

Released to a storm of controversy in Japan, Battle Royale, quickly developed a cult following in the West, no doubt helped by rumours that it was banned in the US (it wasn’t, but legal issues and censorship concerns kept it off screens for many years). A film that prompted questions in the Japanese parliament is now older than the competitors in the game it depicts.

A new form of Battle Royale controversy, as seen in the moral panic regarding video games such as Fortnite and PUBG, has since surfaced and the old arguments about media effects has come back, spearheaded by President Trump among others, in the wake of more school shooting in the US. But what of the original film itself?

Battle Royale still retains the power to shock; it’s difficult not to watch open mouthed at times as a class of forty-two 15-16 year olds set about killing each other. That, of course, is a gross oversimplification of a film in which violence is used as a tool to critique the Japanese education system and their history of a martial culture. That many reviewers, and politicians, concentrated on the film’s violence when it was released only obfuscated the fact that it’s a much smarter film than it might first appear. Yes, it’s violent, but it’s also a film that probes the culture that produces such violence and never holds back from pointing fingers.

It would be easy to lump Battle Royale in with other violent films of the noughties, particularly the rise of torture porn, but that would be to denigrate a film that takes a real interest in its characters and draws from the director’s own experiences of the Second World War. Kinji Fukasaku, best known to Western audiences for his work on Tora, Tora, Tora (1970), took on the film at the age of 71, in part because it took him back to his work in a weapons factory when he was a teenager:

During the raids, even though we were friends working together, the only thing we would be thinking of was self-preservation. We would try to get behind each other or beneath dead bodies to avoid the bombs. When the raid was over, we didn’t really blame each other, but it made me understand about the limits of friendship (Rose 2001).

The limits of friendship are tested throughout as the students of class 3-B are each given a bag of supplies, a weapon, and 3 days to kill each other. Battle Royale takes place in a vaguely futuristic Japan where, after an economic crisis, youth is seen to be running wild. The government’s response, the BR Act, selects a single class from across the country (supposedly at random) and places them in a remote location. Only one of them is allowed to leave. To ensure their compliance each student is fitted with an explosive collar; if they step out of line or if more than one is alive at the deadline their throat explodes.

Although the film mostly follows the rather sweet couple of Shuya and Noriko, Fukasaku takes care to give as many of the students a sense of character as possible. This is expanded in the Special Edition in which the previously psychotic Mitsuko is given a back story that partly explains her character (an incredibly creepy sequence in which she is sold, as a little girl, by her mother to a paedophile whom Mitsuko then kills by accident). This emphasis on character shows a care for the students that lifts them from being cannon fodder. Some are resourceful, some are terrified, some are desperate to lose their virginity before death, but none are identical. It pushes back against the typical view of teenagers as a homogenous mass that threaten society. Indeed, the film clearly suggests that the teenagers are no worse than the culture that created them.

Shuya has been let down by his parents (an absent mother and a father who killed himself, Shuya finding the body), but he shows great resourcefulness and loyalty. Contrast him to the teacher Kitano (played by director ‘Beat’ Takeshi Kitano) who runs the Battle Royale – his life is in tatters: he is alienated from his wife and daughter, and has grown to hate his former class, and the young in general, for making him feel impotent (all except Noriko, for whom he has an unhealthy obsession). It’s a terrific performance by Kitano, which plays on his dual status as director of violent films and game-show host. He is almost impassive throughout only hinting at the inner frustrations his character is riven with, becoming so petty he refuses to share some cookies he swiped from Noriko with the military officers who run the “game”.

Seen very much as a satire on the highly competitive Japanese education system on release the film exposes what happens when people are pitched against each other for crumbs. Of course, inevitably, the game is rigged with two ringers brought in to stack the deck against the students. Just like life, lip-service is paid to fairness, but the reality is far from it. When I first watched the film, when it was released in the UK in 2001, it seemed like a pretty dark and remote vision of how schools could become competitive production lines designed to stifle young-people and scare them into conforming. Having been in teaching for 12 years now it seems much less ridiculous. Reforms to the education system in England are leading to a rise in mental illness in students and one teacher’s comment that “I have at least one student who has attempted suicide, and others with a variety of mental health issues” (Busby) is becoming alarmingly typical, and something I’ve witnessed on a local level. This extends to UK universities where “the suicide rate among UK students had risen by 56 per cent in the 10 years between 2007 and 2016, from 6.6 to 10.3 per 100,000 people” (Rudgard).

An economic crisis followed by an increasingly cut-throat and competitive education system that pits young people against each other in which they are made to feel that their very lives are at stake? Battle Royale is now closer to reality than I find comfortable.

Works Cited

Busby, Eleanor (2018) Pupils self-harm and express suicidal feelings due to exam stress and school pressure, warn teachers. The Independent [online]. Available at https://www.independent.co.uk/news/education/education-news/school-pupil-mental-health-exams-school-pressure-national-education-union-neu-a8297366.html

Rose, Steve (2001) The Kid Killers. The Guardian [online]. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/film/2001/sep/07/artsfeatures2 [accessed 27/07/2018]

Rudgard, Olivia (2018) Universities have a suicide problem as students taking own lives overtakes general population. The Telegraph [online]. Available at https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/04/12/universities-have-suicide-problem-students-taking-lives-overtakes/ [accessed 27/07//2018]

PREFACE

Like many boys who grew up in the 1980s I developed a close relationship with the James Bond films.

A perennial fixture on British television, and at the local video rental, the films were ones I watched and re-watched. For m

any years my favourites were the Roger Moore films, especially The Spy Who Loved Me, Moonraker and Octopussy. They were light and fun and simple to follow. Around 1989, at the grand age of 10, I found my tastes shifting. This was probably due to the onset of adolescence, but also the effect of the new, dark-gothic, Batman film which providing a richer form of escapism than I was used to. This in turn lead me to the comics of Frank Miller and Alan Moore, adding more layers to a character I had once known in Adam West’s fabulously campy performance. And into my nascent more cynical world came Timothy Dalton’s Bond films.

Dalton’s Bond has always been something of a problem. When the films came out, The Living Daylights in 1987, Licence to Kill in 1989, critical reaction was split. Over the years, spurred on by the lapse in production between Licence to Kill and Goldeneye in 1995, and Dalton’s decision to step away from the role after only two films, there has grown a consensus that the films are failures (particularly Licence to Kill). Whereas the once reviled On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (1969), and its star George Lazenby, have been revisited and reappreciated Dalton’s two films remain in the shadows of what came before and after. This was not helped by the dip in box-office that Licence to Kill encountered when it was released into the summer of 1989 when Batmania was in full swing.

During that gap of six years I, however, discovered them. They existed only as VHS recordings of edited versions shown on television, but I didn’t know any better. They led me to reading all of Fleming’s Bond novels (and most of John Gardner’s continuation series), revisiting the earlier Connery films and, in a proper sign of teenage obsession, joining the official fan club whose publication 007 Magazine I devoured ravenously.

With no new movies to watch I could only look back and took to memorising as much information as possible. I was a full-blown Bond nerd.

When 1995 rolled around I had become manic in expectation of James Bond’s return. I would scour the papers for news, buy any magazine that had Pierce Brosnan on the cover, tape the Tina Turner music video when it was on television and watch it back for clues as to the film’s content. This was, of course, before the internet so spoilers were much harder to come by. The novel adaptation was duly absorbed, the television spots and trailers waited for, in a sense of almost religious fervour. And then it debuted, and it was as good as anything I could have hoped for. Goldeneye seemed to unify Connery and Moore while the film updated the traditional Cold War setting in a clever and relevant way. Bond was back on top.

Yet something was a bit off. It was during the opening sequence – itself an excellent stream of action and stunts – that it became evident. It was set in 1986. With one stroke Dalton’s films were removed. In all probability the date was a reference to when Brosnan was first cast as Bond (only to be denied by his television contract) but it felt like an odd slap in the face to a Dalton fan. As Brosnan’s films descended into special effects, thin characterisation and absurdity, Dalton’s films grew for me. Here was a version of Bond that seemed closest to Fleming, a more grounded sense of the character to whom killing wasn’t a game and the women weren’t so disposable. Dalton would never have worn x-ray glasses or driven an invisible car, nor have such a penchant for kissing dead women.

Die Another Day relieved me, after 12 years, of my Bond obsession. Sure, some of the Moore films were bad, in retrospect, but this was worse (not helped by some poor CGI and the stunt casting of Madonna). The producers seemed to know it and, despite healthy box-office, took the radical decision to reboot the series.

So, why return to Dalton now? It’s coming up to 30 years since the release of Licence to Kill and it remains in many circles an underappreciated film. This book is intended to draw greater critical attention to Dalton’s films and reevaluate them as a radical attempt to change the Bond series for the better.

In an interview in 2014 Dalton opened up about why he left the series. A man who was never comfortable with global fame and the associated intrusion into his private life discussed how he would have to commit to more films to continue. He was unwilling to make such a commitment: “I thought, oh, no, that would be the rest of my life. Too much. Too long. So I respectfully declined” (Meslow, 2014). It occurred to me that Dalton had disagreed with something that ate him.

The info on my upcoming book:

HE DISAGREED WITH SOMETHING THAT ATE HIM analyses the two James Bond films starring Timothy Dalton made in 1987 and 1989. Critically overlooked and often seen as a misstep for the series the author argues that both films are a unique contribution to the series and form an important dialogue with the rest of the franchise.

By placing the films within the context of the Bond series and the works of Ian Fleming, Cary Edwards argues that The Living Daylights and, in particular, Licence to Kill, are a radical attempt to return Bond to his literary origins, while aiming the film franchise towards a more adult audience.

This article was first published by Bright Lights Film Journal on January 16 2018 (http://brightlightsfilm.com/watch-it-again-society-brian-yuzna-1989/).

After nearly 30 years Society has become a perfect film for the age of Trump.

A withering satire on the American dream Yuzna’s film deserves to be rediscovered as one of the most odd, interesting and radical of American horrors. Hiding under the guise of a teen horror is an attack on the myth of the classless society, a (quite literal at times) peeling back of Reagan’s America in which growing inequality is dressed up in Hollywood gloss. Its message, that the rich operate a closed society in which they exploit the rest of America, has now become more relevant than ever.

As an outsider looking in America’s dedication to seeing itself as a classless society has often seemed a little absurd. From the UK, where class pretty much defines everything, the stratification of America in terms of class looks strangely familiar. Despite this a recurrent desire to define America as a society in which everyone is effectively middle class continues. Trump’s ascension is the story of man living off inherited wealth using rhetoric to de-class himself to appeal to disaffected, and often laid-off, manual workers. That this worked, despite the fact that he is exactly the type of asset stripper and outsourcer responsible for the economic status quo, demonstrates the power of myth in society. Whatever the particular niceties of Trump’s ability to make himself seem like a “regular guy” it’s a well-worn trope of American culture that he tapped into, one that turned against Hilary Clinton tainted, as she is, with the whiff of elitism.

This unwillingness to confront class divisions extends into American cinema, where the American dream is consistently reinforced and class is hardly ever a barrier for those who want to work hard. In many ways the Rocky franchise stands as the apotheosis of the myth of a culture in which everyone gets their shot at the title. Social mobility, we are repeatedly told, is available to all just as long as you work hard enough. The success of Stallone, and his 1980s rival Schwarzenegger, reinforced this myth as much as their films did – the self-created stars who through force of mind and body could transcend their poor origins to rise to the peak of Hollywood success.

For most, of course, this never happens. For every success there are numerous hard working people buying into the dream and never getting anywhere. In Society this exclusion from getting on is transformed into a world where the rich are not just different, they’re not human, and they literally feed off the poor.

Having made some waves in horror as producer of Re-Animator (Stuart Gordon, 1985) and From Beyond (Stuart Gordon, 1986), both based on Lovecraft and both employing body horror, Yuzna took a decidedly left turn with his directorial debut – it’s truly a film like no-other. Yes, it supplies the body horror, ably created in all its sticky glory by Japanese effects expert Screaming Mad George, but it fuses it with teen movie, conspiracy thriller and absurdist comedy in a way that would make Dr Herbert West proud.

On the surface Society plays on recurrent adolescent fears of entering adulthood, especially in the realms of sexual relations. In many horror films, especially in the Slasher sub-genre, anxieties faced by the adolescent are dramatized; the killer, or monster, which must be conquered stands in for the desires/fears that need to be repressed for successful entry into the symbolic order. That the monster has a sexual ambiguity to it has been noted and extensively examined (particularly by Carol Clover). In many respects Society follows this formula as it centres on Billy Whitney (Billy Warlock[i]) a High School student. Billy is popular, has a cheerleader girlfriend, and has recently acquired a new Jeep Wrangler. However, and though he visits a re-assuring psychiatrist, a tape recording shared with him by a fellow student, Blanchard, reasserts Billy’s belief that there is something wrong with his family and their friends and, by extension, the wider high-class society he is part of but feels alienated from. Through various scenarios Billy’s paranoia develops until all is revealed – he is really a fatted calf, raised to be sacrificed in the Shunting, an orgy of twisted bodies where normal people are absorbed by the higher ups – judges, politicians and business leaders. It’s a hysterical sequence that paints the ruling class as sexual perverts who prolong their, possibly eternal, existence by draining life from the poor.

On the surface Society plays on recurrent adolescent fears of entering adulthood, especially in the realms of sexual relations. In many horror films, especially in the Slasher sub-genre, anxieties faced by the adolescent are dramatized; the killer, or monster, which must be conquered stands in for the desires/fears that need to be repressed for successful entry into the symbolic order. That the monster has a sexual ambiguity to it has been noted and extensively examined (particularly by Carol Clover). In many respects Society follows this formula as it centres on Billy Whitney (Billy Warlock[i]) a High School student. Billy is popular, has a cheerleader girlfriend, and has recently acquired a new Jeep Wrangler. However, and though he visits a re-assuring psychiatrist, a tape recording shared with him by a fellow student, Blanchard, reasserts Billy’s belief that there is something wrong with his family and their friends and, by extension, the wider high-class society he is part of but feels alienated from. Through various scenarios Billy’s paranoia develops until all is revealed – he is really a fatted calf, raised to be sacrificed in the Shunting, an orgy of twisted bodies where normal people are absorbed by the higher ups – judges, politicians and business leaders. It’s a hysterical sequence that paints the ruling class as sexual perverts who prolong their, possibly eternal, existence by draining life from the poor.

Under the guise of a teen horror Yuzna manages to twist familiar genre tropes in service of his political message. The high class setting immediately sets Society apart from other teen horrors of the era as it eschews the everyday nature of most where-in, such as in A Nightmare on Elm Street (Wes Craven, 1984) and Halloween (John Carpenter, 1978), the main characters are located in a ‘regular’ neighbourhood, remarkable only in its interchangeableness with those in other teen horrors or in the isolated teen-spaces such as the camp, as in Friday the 13th (Sean S. Cunningham, 1980). Society is also different in having a male protagonist rather than the final-girl that features in most, if not all, 1980s teen horrors – a male teen idol who, for many, could stand in for wholesome values. Society plays a subversive game with genre, moving the familiar context to one which appears aspirational, and tied to mainstream ideas of success. The Whitney household is a Beverley Hills mansion, pristine and white, overtly displaying the wealth and advantages Billy expects to inherit – however his alienation from this lifestyle is evident from the beginning and is also encapsulated in his appearance: dark-haired when the rest of the family are blonde, shorter than his sister and school colleagues (he is literally looked down on by this ideal, Aryan, family). “They don’t even look like me” he tells Dr Cleveland, but the difference also suggests a paranoia that the film plays on, editing being used to undermine Billy’s gaze, replacing disturbing images with those that are more normal and asking the audience to question the reality placed before them.

The opening of the film foregrounds this willingness to be subversive and to blur boundaries between reality and fantasy. A typical dream sequence occurs in which Billy, clutching the classic slasher weapon of the kitchen knife, walks scared through his own house, only to be confronted by his mother all the while a female voice sings a haunting rendition of the Eton Boating Song (reminiscent of the use of nursery rhymes in the Elm Street series and tying the film to old-world class structures). The film cuts to the psychiatrist’s office where Billy confides his feelings of fear and dread to Dr Cleveland. Billy takes an apple and bites, revealing worms within. It’s an obvious but still potent symbol of the corruption under the skin in this supposed Eden. Then, adding another surreal layer, it cuts to a flash-forward of the Shunting, allowing us to see merged body parts, covered in a sticky fluid with muted moans as the Eton Boating Song Resumes with a new re-written lyric;

The opening of the film foregrounds this willingness to be subversive and to blur boundaries between reality and fantasy. A typical dream sequence occurs in which Billy, clutching the classic slasher weapon of the kitchen knife, walks scared through his own house, only to be confronted by his mother all the while a female voice sings a haunting rendition of the Eton Boating Song (reminiscent of the use of nursery rhymes in the Elm Street series and tying the film to old-world class structures). The film cuts to the psychiatrist’s office where Billy confides his feelings of fear and dread to Dr Cleveland. Billy takes an apple and bites, revealing worms within. It’s an obvious but still potent symbol of the corruption under the skin in this supposed Eden. Then, adding another surreal layer, it cuts to a flash-forward of the Shunting, allowing us to see merged body parts, covered in a sticky fluid with muted moans as the Eton Boating Song Resumes with a new re-written lyric;

Oh how we all get richer

Playing the rolling game

Only the poor get poorer

We feed off them all the same

Then we’ll all sing together

To society we’ll be true

Then we’ll all sing together

Society waits for you

This layering is disconcerting in its denial of familiar tropes and the missing context for the images. Billy we can presume is the protagonist, but his circumstances straddle an umheimlich situation, wealth familiar from various soap-operas, commercials and glossy magazines, juxtaposed with paranoia, anxiety and mutated bodies. The lighting and Dutch-angle of the opening sequence situate the film firmly in the horror genre, but the following shots disturb the reassurance any generic recognition might bring.

Society also takes the metaphorical desires and problems of other teen-horrors clear and makes them obvious. Halloween, in its first person prologue, hints at incestual desire as Michael Myers kills his half-naked older sister immediately after she has had sex with her boyfriend. Society deliberately places Billy’s sister Jenny as a figure of desire, both for Billy and the spectator, in a scene where she showers. However as it foregrounds this desire, it simultaneously undermines and perverts it by suggesting an unnatural and impossible configuration of body parts; Jenny’s torso appears twisted so that both her breasts and buttocks appear through the frosted glass. This highlights one issue, the amorphous bodies of the Shunters, and also implies an incestual element to the gaze. In Elm Street the sins of the parents, in their killing of child murderer Freddy Kruger, is played out on the bodies of the teenagers while their parents exist in incompetent denial. In Society the parents are the sin, a secret hidden in plain sight, their bodies the site of perversion and horror.

The fluidity of the human body on display in Society differentiates it from earlier examples in the genre and is indicative of contemporary sexual politics, especially in light of the aids crisis during the 1980s. The Shunting sequence sees body parts swap place and people intertwine. Yuzna uses some of this for humour, Billy dad becoming a literal “Butt-head”, and some to push boundaries linked to sexual hysteria: the incest between Jenny and her mother, the gay kiss between Ferguson and Billy. Most pertinent is the emphasis on penetrability of the human body, especially the penetrative potential of the male anus, through which both Blanchard and Ferguson are killed. The merging of the human bodies that occur during the Shunting evokes the female body in several ways, not only in the representation of penetrability. Through a perverse eroticism is evident in Society, finding its apotheosis in the Shunting. Both objects of Billy’s desire, his sister and eventual love Clarissa, twist their bodies at the waist. The anus again becomes visible and accessible to the male. This homo-erotic anxiety pervades then throughout the film, initially played out on the bodies of women, then seen more obviously during the Shunting. It is Billy’s ability to avoid penetration, and his penetrating of Ferguson, that allows him to escape. This subverts his class role (as member of the under-class) but disavows the homo-sexual eroticism from earlier in the text.

The sexual anxieties that run through the film connect directly to the class rules of American society in which the majority are encouraged to live sexually “normal” lives of heterosexual monogamy. The upper orders are free to indulge their perversities safe in the knowledge that the Police will protect them, rounding Billy up in the film. Access to the higher sections of American society is prohibited too, Billy losing his High School election despite being the most popular student in School (which also costs him his girlfriend). All his entitlements are stripped away from him in the film as it becomes clear he is not one of “them”, his dream-life crumbling. Rounded up by the authorities Billy, and us, witness the Shunting, an orgy organised in honour of a Judge and attended by various figures from Washington in which Blanchard is drained of his nutrients. Finally Billy realises that he is adrift in a society he cannot enter and one that sees him as food, his paranoia is real – Society is designed to work against him. The end of the film leaves the status quo intact, the powers that support are to large to simply be undone by one man.

A flop on release in America (two years after production) Society found an audience in Europe where class divisions are more openly acknowledged. It deserves to be rediscovered in modern America as a radical departure from genre norms, but also as one the most searing critiques of the American Dream.

Works Cited

Clover, Carol (1993) Men, Women and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. London: BFI Publishing.

[i] Warlock’s casting adds an intertextual meaning due to his role in The Days of Our Lives preceding Society. The long running soap-opera features the aspirational life-style satirized in Society.

Coming soon from Cinephiles Press – He Disagreed with Something that Ate Him, a critical reading of Timothy Dalton’s two Bond films The Living Daylights (John Glen, 1987) and Licence to Kill (John Glen, 1989).

Press Release Info:

He Disagreed With Something That Ate Him analyses the two James Bond films starring Timothy Dalton made in 1987 and 1989. Critically overlooked and often seen as a misstep for the series the author argues that both films are a unique contribution to the series and form an important dialogue with the rest of the franchise.

By placing the films within the context of the Bond series and the works of Ian Fleming, Cary Edwards argues that The Living Daylights and, in particular, Licence to Kill, are a radical attempt to return Bond to his literary origins, while aiming the film franchise towards a more adult audience.

This paper was originally presented to London Film & Media 2011, and published in The London Film and Media Reader 1.

The Vigilante Thriller

This essay considers the condemnatory and heavily ideological critical reactions to a cycle of US vigilante thrillers from the 1970s. The cycle includes Straw Dogs (Peckinpah, 1971), The French Connection (Friedkin, 1971), Dirty Harry (Siegel, 1971), Death Wish (Winner, 1974) and Taxi Driver (Scorsese, 1976). A common accusation was that the films were ‘fascist’, made by ‘fascists’, or liable to encourage ‘fascism’ in the film audience. This was not a label that was necessarily rejected by all the film-makers – certainly Sam Peckinpah enjoyed baiting reviewers and interviewers with a series of abrasive, and often, contradictory statements – but the consistency of this criticism highlights an anxiety in the critical reactions about the meanings of these films and, on closer inspection, the meanings of the violence they portray.

Although the critical writings are an important reaction to the texts, discourse analysis reveals a series of inconsistencies and contradictions in their assumptions about the ways in which a film can be watched. Rather than relying on these critical responses alone to guide us in terms of spectator reaction, we should instead be analysing what Ellis terms the ‘narrative image’,

“an idea of the film [that] is widely circulated and promoted … the cinema industry’s anticipatory reply to the question ‘what is this film like?’” 1

It is important to investigate how this element of para-text fixes, or aims to fix, the spectator’s experience, since the narrative image is also essential in fixing the modality of the film text. Following Hodge and Tripp, ‘modality’ is being used here in the sense that it “concerns the reality attributed to a message.”2

This has specific implications for the reception of film violence, and it is the understanding of violence that I wish to concentrate on in this essay. These distinctions were missed by contemporary critics, who ignored the concept of modality, tended to see film violence as a singular issue, and recycled basic tropes about the effect that film violence might have on the audience. Despite the consistency of the critical reaction to these films, the narrative image of each film suggests a range of spectator positions. The desire to elide these films on the part of contemporary critics, on the other hand, signals a wish to simplify the spectator experience and ignores the shifting relationship that a spectator can have in relation to several connected but different texts.

Critical Reactions: The Politics of Violence

Even a cursory glance at the American and British popular press reaction to these films reveals two central concerns, both of which are linked to the possible effect of the films on the audience and the wider implications for society. The first concern, highlighted more by the American critics than the British, is the suggestion that these films convey and promote a fascist sensibility. The second concern, which is present on both sides of the Atlantic, concerns the portrayal of violence. This is often linked to a perceived increase in the amount of violence being portrayed in film, the explicitness of the violence, and the sense that the films in question encourage the spectator in turn to be violent.

Pauline Kael’s critical reaction to the films exemplifies the general tone of the reviews. For Kael, Straw Dogs is a “fascist work of art”3 that presents the “triumph of a superior man”. Dirty Harry is a “right wing fantasy” that attacks “liberal values” and draws out the “fascist potential” of its genre4. The French Connection, for its part, features “the latest model sadistic cop”5. Gareth Epps draws wider conclusions from Straw Dogs, The French Connection and Dirty Harry such as

“it has been obvious for a long time that American filmmakers are unable to deal with the politics of the left in any recognizable way”6 .

These films, he suggests, are symptomatic of a wider right-wing tendency in Hollywood. He adds that “recent American films have begun to show a frightening sophistication in at least one area of politics – the half-world of sadism and authoritarianism which is the breeding ground of the fascist mentality”. The accusation that the films are characterised by ‘fascist’ ideology betrays an anxiety in the reviewers towards the shifting political landscape in America through the 1960s and into the 1970s.

The effects of the Vietnam War on the collective American consciousness cannot, of course, be ignored. However the shifts in civil rights movements, crime and policing are also important here. The elements that were picked out from these films and directly linked to fascism included the representations of masculinity, race and violence. From a didactic point of view, however – and many of these reviews and reactions were written in a didactic mode – there is a recurrent flaw, namely an inability to define exactly what fascism is. Its recurrent use as a blanket term in reaction to these films shows a remarkable inconsistency in its application, and also a sense that the word is being used as a short-cut, a way of marking a text as unacceptable, with no underlying understand of the word and its political/philosophical application.

Critical Reactions: Violence and Spectatorship

If fascism is one recurrent way of condemning these films, the other anxiety that emerges is the meanings and implications of violence in the films. As has been noted elsewhere, the depiction of violence in American cinema changed radically in the 1960s and 70s. There are various reasons for this, including the influence of non-American films, and the eventual dissolution of the Hays code. More important perhaps was the shift in the representation of violence on television where, from the shooting of LeeHarvey Oswald by Jack Ruby to the reports from the front line in Vietnam, violence was being shown more often and more explicitly.

Of course this form of violence, presented in news programmes, has an inherently high modality despite its mediated nature. In this atmosphere of a shifting depiction of violence, combined with a greater perception of violence in society through rising crime rates and civil unrest, the implications of watching – and more importantly enjoying – film violence became a point of anxiety for contemporary critics. The reviews of Taxi Driver generally avoided the same ideological criticism as the other films and one wonders if this is linked to the potential audience for such a film. Kael suggests, in reviewing The French Connection, that

“Audiences for these movies in the Times Square area and the Village are highly volatile. Probably the unstable, often dazed members of the audience are particularly susceptible to the violence and tension on the screen”7.

It is clear that a strain of elitism has entered the critical reaction here.

The New York Times felt the need to send reporter Judy Klemesrud to a theatre to gauge reaction to Death Wish, asking “What do they see in ‘Death Wish’?”. Klemesrud interviewed audience members and “Three mental health professionals” in the course of her quest.8 I think it’s important here to highlight the suggested opposition in that headline – “they” are clearly not “us”, “us” referring to those sophisticated enough to read the New York Times. Across many reviews and articles on both sides of the Atlantic there is a clear fear concerning the possible impact of a text on a supposedly less sophisticated audience.

These reactions were not without their contradictions. Charles Barr, for instance, noted the differences between the British critical reaction to Straw Dogs and A Clockwork Orange (Kubrick, 1971). 9 His conclusion, that the reaction differed because of the way in which violence was presented by each film – for example, by the use of telephoto lenses in Straw Dogs compared to the use of wide angle lenses in A Clockwork Orange – signals the inconsistency in the criticism of films marked as violent.

Stylistic distinctions are then critical, Barr argues, for understanding the ways in which the films operate: Minute-for-minute, A Clockwork Orange contains more instances of violence than Straw Dogs, but Straw Dogs does not allow the spectator the luxury of remaining distant through the use of the wide-angle lens. The fear of what Straw Dogs implied for cinema and the audience nonetheless moved thirteen British critics to write to The Times to decry the film’s certification, expressing their “revulsion” at the film and its marketing.10 In other reactions we see a clear perceived link between the film text and possible audience reaction (The Guardian, for example, felt strongly enough to send a reporter to New York to examine how Death Wish was inspiring American traditions of gun ownership).

The underlying fear in many of the critical reactions was that the audience, having watched the film, would themselves become vigilantes. That the critics themselves didn’t burst out of auditoria and beat up some muggers seems to have escaped their attention. Moving away from the discourse concerning the supposed effects of film violence we also encounter an inconsistency among critics to accurately differentiate between different types of violence, an inability to recognise the difference between the nature of the act being represented, and the method of its representation.

Modality and Narrative Image

The elision that the contemporary critics made between these films ignores the importance of the narrative image in conditioning the modality of the spectator’s engagement. Even if we acknowledge the polysemic nature of film texts and their para-texts, dominant themes from the marketing of the films suggest ways in which the spectator is primed to watch and respond to a text. The narrative image tells us the frame of mind in which a spectator receives a film; this in turn suggests a level of modality in which the spectator will receive the film violence. To suggest that all film violence can be measured the same way is to ignore the differing modalities of films. In short, not all film violence is equal.

The decision the spectator makes about whether to watch a film will often rest on several factors. One of the key elements is the marketing and promotional material of the film. When examining these for each film we see that they suggest several different ways in which to receive and understand the violence of the films, something typically ignored by the critics. We may thus conceive of the spectator as having a personal and private relationship with a film that takes place within the cinema, but we should also acknowledge that the spectator’s experience of the film begins with several para-textual factors that help condition their subsequent experience.

Take, for instance, the use of violence in the poster imagery for the films. Straw Dogs, whose central image is a close-up of Dustin Hoffman with one lens of his glasses broken, signals violence, but also the effect of violence on the protagonist. The French Connection uses a still of ‘Popeye’ Doyle shooting a suspect in the back as its main image. Dirty Harry concentrates on the persona of Clint Eastwood (but also the duality between the two main characters), while Death Wish uses the image of Charles Bronson. Taxi Driver’s central image, of a lost and isolated Travis Bickle posed in front of a New York street scene locates an alienated figure in a world of degradation.

This image for Taxi Driver places the spectator in a very different relationship to the violence of the text than the other posters. By not signalling the violence but concentrating on the alienation of the protagonist (in effect hiding the violence), the poster prepares us for a film where acts of violence, when they do occur, have greater weight. The casting of De Niro (still relatively unknown at this point and thus ‘absorbed’ by his role in the film), and the setting of the film in real areas of New York, confer a high modality.

This is reinforced by the presentation of the violence in the film. This is not expected in the same way as in an Eastwood or Bronson film, where violence is an inherent part of the experience. Indeed the marketing of both Dirty Harry and Death Wish so connects the characters to their actors as to create a direct intertextual link to their other films. In these circumstances film violence becomes a ritualised part of the cinematic experience. The French Connection, however, with its concentration on reality, linked to the oft-repeated information that the film was based on real events, suggests a higher modality for the film violence which it contains.

We are watching here a reproduction of real violence, not the heightened and stylised violence of an Eastwood or Bronson film. The ritualisation in Dirty Harry and Death Wish confers a lower modality on the violence, which has become part of the expected generic formula of the text, an inevitable and unsurprising element. Through its enigmatic title and ambiguous central image, on the other hand, Straw Dogs denies the spectator a secure sense of how violence will operate in the film.

Generic Contexts

The explicitness (or lack) of generic context creates other issues here. It has been noted, for instance, that both Dirty Harry and Death Wish bear relation to the Western film, in casting (the stars of both had previously appeared in successful Westerns), iconography and structure. Perhaps the relocation of the generic elements to a modern day location, stripping away the mythic trappings of the narrative, creates this discomfort around the violence.

The recognition of Western genre conventions in the narratives of Dirty Harry and Death Wish may confer a different level of modality than a film such as Taxi Driver, which has a less clear generic definition. The ritual of genre, the procession of structural and iconic elements, reminds the audience that what they are watching is a structured creation – when it runs true to form, the text offers much reassurance but little by way of surprise. This, I would propose, effectively lowers the modality.

Too often film violence is taken out of the context of reception. Film violence occurs within several frameworks, including the textual implications of narrative and genre. The narrative image of a film is explicit in its attempts to set up these elements for the spectator. Thus the debate about film violence should be embedded in not only the referential and aesthetic components of film violence, but also in analysis of the place that violence has within the contextual, paratextual and textual experience of the film. For contemporary critics of these films however, socio-political concerns of the day outweighed the specifics of the textual/para-textual experience.

Notes and References

1 John Ellis, Visible Fictions: Cinema, Television, Video, London: Routledge, 1982, p. 30.

2 Bob Hodge and David Tripp, Children and Television, Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers, 1986, p. 104.

3 Pauline Kael, Deeper into Movies: The Essential Collection, from ‘69 to ’72, London: Marion Boyars, 1975, p. 398.

4 Kael, Deeper into Movies, p. 385.

5 Kael, Deeper into Movies, p. 316

6 Gareth Epps, ‘Does Popeye Doyle Teach Us How to be Fascist?’, The New York Times, 22 May 1972, II:15, p. 1.

7 Kael, Deeper into Movies, p. 316.

8 Judy Klemesrud, ‘What do they see in Death Wish?’, New York Times, 1 September 1974, II:1, p. 5.

9 Charles Barr, ‘Straw Dogs, A Clockwork Orange and the Critics’, Screen, vol. 3 no. 2, 1972, p. 23.

10 Fergus Cashin, John Coleman, N. Hibbin, Margaret Hinxman, Derek Malcom, George Melly, T. Palmer, J. Plowright, Dilys Powell, David Robinson, John Russell Taylor, Arthur Thinkell, and Alexander Walker, ‘From Mr. Fergus Cashin and Others”, The Times, 17 December 1971.