Full disclosure: Cobra is not a good or interesting film in any of the traditional ways. It lacks narrative coherence, the story is bare to non-existent, and the performances are largely one-note. It is, however, a film that allows us to explore how the audience can be employed in the creation of meaning. In fact I’d go as far to suggest that the audience really makes the film themselves due to it being thoroughly disjointed. In effect, the spectator becomes the main agent of meaning culling from their own understanding of genre, narrative and various intertexts in an act of creative spectatorship. In this Cobra emerges as a key action text of the 1980s, telling us just how tuned into the genre action fans were.

To say that Cobra was critically unloved on its release would be something of an understatement. Nina Darnton, in The New York Times, suggested that the film was “disturbing for the violence it portrays” and showed “contempt for the most basic American values embodied in the concept of fair trial”. Sheila Benson, in the Los Angeles Times, cited the films “pretentious emptiness, its dumbness, it’s two-faced morality”. David Denby went even further titling his New York Magazine review “Poison”, and comparing Cobra to Dirty Harry (Don Siegel, 1971), citing the former’s lack of “the peculiar sad gravity that Clint Eastwood gave him.” None of this seemed to harm Cobra’s box office, with it gaining $49 million in the US alone (ww.boxofficemojo.com), and totalling $160 million worldwide (Fisher, 2016), helping to continue Stallone’s profitable run at the box-office (although it did show a significant drop from the less explicitly violent Rocky and Rambo films).

Revisiting the film now, one wonders why the reviewers were so worried as it’s such a disjointed and unbelievable film that its clearly addresses its audience in a self-conscious post-modern and shallow manner, to the point where it becomes sort of sub-Brechtian in its emptiness (although politically it’s about as far from Brecht as you can get in its continual celebration, and destruction, of consumer products). The critical comparisons to Dirty Harry are revealing as it’s in this that Cobra starts to come alive as a film, drawing much of it’s meaning from the earlier film series (it’s also notable that Dirty Harry was decried in similar ways on release). The opening of the film directly imitates the second Dirty Harry film, Magnum Force (Ted Post, 1973), both culminating in the hero’s gun firing out of the screen at the audience (immediately breaking the fourth wall and puncturing any claims to an immersive experience). The conflict between Cobretti (Stallone) and his superiors is lifted almost directly from the Dirty Harry films, but is subverted somewhat by the casting of Andrew Robinson who played the Scorpio Killer in Dirty Harry.

Here, as Detective Monte, he continually challenges Cobretti – suggesting that the audience, upon recognition of Robinson’s distinctive face and voice should conclude that if that psycho thinks Cobretti is too violent, he must be heavier than Harry Callahan. Casting Reni Santini as Cobretti’s partner is a direct call-back to the almost identical role he played in Dirty Harry, both characters even being called Gonzales (the only discernible difference in the performances is a hat). The film sutures together the plots of the Dirty Harry films (excluding The Dead Pool, released in 1988) – the psychotic killer of Dirty Harry (now The Night Stalker), the fascist group from Magnum Force merges with the terrorist group of The Enforcer (James Fargo, 1976), with elements of the romantic relationship in Sudden Impact (the character of the turncoat cop Stalk in Cobra also looks very similar to unpleasant butch-lesbian stereotype Ray in Sudden Impact (Clint Eastwood, 1983)). At this point the film is directly drawing from these films in a very knowing manner, clearly assuming that the audience knows the other texts – this knowledge functions as a series of narrative and characterisation short cuts. Exposition is barely required as the audience is already aware of how this narrative will play out – the opening action scene, in a grocery store, imitates similar Dirty Harry scenes, without requiring any sense of location or time – it is enough that a crime has occurred. Ritualistically we expect Cobretti to arrive and solve the problem, which he duly does, so no suspense or tension is created or necessary. It becomes a scene entirely designed to showcase how much dirtier Cobretti is than Harry (Cobretti wears his mirrored shades all the way through the scene; he pauses to sip from a Coors; his killer also has a bomb; he has his own catchphrase “You’re the disease, I’m the cure.”) Thus, the film works on a ritualistic and generic level, playing out exactly as expected in some ways, despite some particularly curious directional choices we’ll come to.

On an intertextual level it’s also worth discussing how the films’ studio backing primes the audience for the content. As both a product of The Cannon Group and Warner Brothers (as distributor) the studio logos that start the film suggest an uneasy nexus point between one studio known for cheap exploitation/action pictures and another with a rich history but also, during the 1980s, a skewing towards action films (Warner’s would in 1988, after all, give the world the dubious gift of Steven Seagal). Of course, the Warner link pulls straight back to Dirty Harry, whereas the Cannon group evokes the world of Charles Bronson and Chuck Norris and ultra-violent fayre like The Exterminator II (Mark Buntzman, 1984). Given the strength of the growing home-video market Cannon had become well-known, if not infamous, to audiences but the Warner Bros. logo gives the film a sheen of quality (original trailers trade on the Warner logo more than the Cannon connection). It’s also one of the first 80s action films to be set at Christmas, beating Lethal Weapon and Die Hard to the punch. Not that the Christmas setting has much purpose, other than occasional pans over nativity scenes or Christmas trees incongruous to the sunny LA setting, perhaps left over from the previous years Cannon action ‘epic’ Invasion USA (Joseph Zito, 1985).

The opening narration sets the tone for the film, but also a premise from which the subsequent action is contextualised to make sense;

In America, there’s a burglary every 11 seconds, an armed robbery every 65 seconds, a violent crime every 25 seconds, a murder every 24 minutes and 250 rapes a day.

With this, delivered in Stallone’s familiar drawl, the justification of all the violence that subsequently occurs is drawn (ironically Cobretti kills way more people than The Night Stalker manages). It’s worth noting that during 1986 there was an upswing in homicide (Wilkerson, 1987) but also that Cobra draws no attention to causes – the film exists in a Manichean universe in which archetypes, far removed from reality, battle each other.

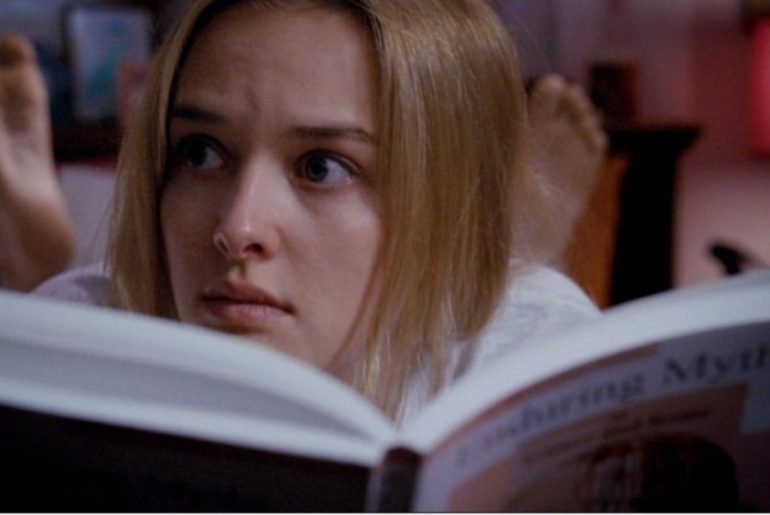

After the voice-over opening and before the grocery store action sequence the first of several montages plays out which are directed in an almost surreal manner, bearing more comparison to the work of Eisenstein in the juxtaposition of images than in a typical Stallone/Rocky training sequence. These contextless disconnected images of men clashing axes together, tattoos, graffiti and a motorbike are intercut rapidly giving the audience all the introduction to the films far-right group they’ll ever get or need (their politics almost subliminally suggested through their skull and axe logo). But of course, the audience needs no more introduction, it’s enough that these people exist to be opposed. A second montage, in which both Cobretti and The Night Stalker search for murder witness Ingrid (Brigitte Nielsen), set to Robert Tepper’s Angel of the City, cuts between protagonist and antagonist and Ingrid during a bizarre fashion shoot in which she drapes herself around various robotic creations – it introduces some almost avant-garde imagery into proceedings for no discernible purpose. Ingrid’s career, as a model, indicates her purpose in the film – beautiful object, nothing more.

From here the film proceeds much as one would expect, and yet lacks many of the elements of character and dialogue any competently made Hollywood movie would have. Much of this relates to the disputed direction of the film, with some claiming that Stallone directed the film himself (when he wasn’t busy off set consummating his recent marriage to Nielsen). He certainly wrote the film (as much as it has a script) ditching any part of the novel Fair Game by Paula Gosling on which it is nominally based. It also has a troubled post-production with numerous cuts being made to secure an R-rating and to increase showings, removing around 30 minutes of material. Although this editing creates numerous continuity errors it plays into the audience’s ownership of the narrative, making them work to film in the gaps and the cuts remove the superfluous elements that the audience knows anyway.

And then there’s the hero, Stallone’s Marion Cobretti first-named, one assumes, in tribute to John Wayne (at one-point Stallone spins his semi-automatic Colt, with cobra picture on the grip, round his finger despite the fact this would, in all likelihood, result in him shooting himself). Even by Stallone’s standards his performance is low key, a sleepy re-tread of previous performances marked only by his continued wearing of gloves and innovative way of eating pizza (watch it, it’s very odd).

Cobra exists purely as a series of attitudes, instead of a performance per se. The romance, between Cobra and key witness Ingrid), is particularly pallid but is part of where the film extends out from film and into Stallone’s real life – the fact that they were married in real life creates the sense that they’re a couple, so small details such as chemistry or interplay are moot. Similarly, the serial killing, far-right leaning, villain is played by Brian Thompson who bears a resemblance to Stallone’s great box-office rival Arnold Schwarzenegger (who himself was, for a time, dogged by rumours of far-right leanings and an admiration for Hitler (Left, 2003)). Again, the lack of characterisation is subverted through the casting, reaching into Stallone’s own life and rivalries as a short-cut.

Scratch away at Cobra and one finds various palimpsests – the Dirty Harry films, Stallone’s own life and career, the Cannon imprint – and these are essential for understanding the film’s popularity. On its own it’s an incoherent piece, but as an intertextual construction it starts to make a certain amount of sense. It is Stallone’s life and career up to that point culminating on screen, taking aim at one of his direct progenitors while jabbing at the current competition. It remains, in most respects, quite a bad film but it’s one that highlights how the audience can be engaged beyond the text itself to create narrative and meaning – it’s a film that operates in the audience’s understanding of narrative and archetypes, allowing such niceties as character and plot development to be dismissed.

Works Cited

Darnton, Nina (1986) Film: Sylvester Stallone as Policeman, in Cobra. The New York Times. May 24.

Benson, Sheila (1986) Move Review: The ‘Cobra’ That Saves L.a. Los Angeles Times. May 24.

Denby, David (1986) Poison. New York Magazine. June 9.

http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=cobra.htm [accessed 13/0618]

Fisher, Kieran (2016) Cobra at 30: saluting a Stallone action treat. [online] http://www.denofgeek.com/uk/moviescobra/40861/cobra-at-30-saluting-a-stallone-80s-action-treat [accessed 13/06/18]

Wilkerson, Isabel (1987) URBAN HOMICIDE RATES IN U.S. UP SHARPLY IN 1986. The New York Times [online] https://www.nytimes.com/1987/01/15/us/urban-homicide-rates-in-us-up-sharply-in-1986.html [accessed 15/06/18]

Left, Sarah (2003) Arnie Denies Admiring Hitler. The Guardian. 3 October. [online]. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2003/oct/03/usa.sarahleft [accessed 14/06/18]

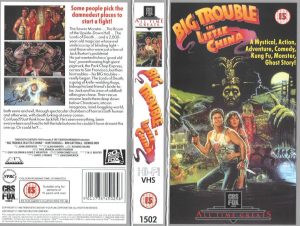

A prologue, filmed at the studio’s behest after they became nervous of Russell’s performance, only serves to build up his character, making the reality even funnier. Chinese mystic Egg Shen (Victor Wong) tells a lawyer that the world “owes a debt of gratitude to Jack Burton”, before we cut straight to Burton’s truck in which he, between mouthfuls of sandwich, speaks ridiculous platitudes to his CB radio:

A prologue, filmed at the studio’s behest after they became nervous of Russell’s performance, only serves to build up his character, making the reality even funnier. Chinese mystic Egg Shen (Victor Wong) tells a lawyer that the world “owes a debt of gratitude to Jack Burton”, before we cut straight to Burton’s truck in which he, between mouthfuls of sandwich, speaks ridiculous platitudes to his CB radio: is a bull-shitting protagonist with no idea what’s going on, blundering into an Asian culture and presuming that everyone there will simply bow down to him and his bluster (shades of Vietnam?). Wang is his friend and allows Burton to tag along in attempts to rescue Wang’s betrothed Miao Yin (Suzee Pai) but it’s extraordinary how useless Burton is, and how little he realises it. Indeed, it’s his posturing at the airport that creates the sequence of events that lead to Miao Yin’s kidnapping – if he hadn’t gone with Wang perhaps none of this would have occurred…

is a bull-shitting protagonist with no idea what’s going on, blundering into an Asian culture and presuming that everyone there will simply bow down to him and his bluster (shades of Vietnam?). Wang is his friend and allows Burton to tag along in attempts to rescue Wang’s betrothed Miao Yin (Suzee Pai) but it’s extraordinary how useless Burton is, and how little he realises it. Indeed, it’s his posturing at the airport that creates the sequence of events that lead to Miao Yin’s kidnapping – if he hadn’t gone with Wang perhaps none of this would have occurred…