Released to a storm of controversy in Japan, Battle Royale, quickly developed a cult following in the West, no doubt helped by rumours that it was banned in the US (it wasn’t, but legal issues and censorship concerns kept it off screens for many years). A film that prompted questions in the Japanese parliament is now older than the competitors in the game it depicts.

A new form of Battle Royale controversy, as seen in the moral panic regarding video games such as Fortnite and PUBG, has since surfaced and the old arguments about media effects has come back, spearheaded by President Trump among others, in the wake of more school shooting in the US. But what of the original film itself?

Battle Royale still retains the power to shock; it’s difficult not to watch open mouthed at times as a class of forty-two 15-16 year olds set about killing each other. That, of course, is a gross oversimplification of a film in which violence is used as a tool to critique the Japanese education system and their history of a martial culture. That many reviewers, and politicians, concentrated on the film’s violence when it was released only obfuscated the fact that it’s a much smarter film than it might first appear. Yes, it’s violent, but it’s also a film that probes the culture that produces such violence and never holds back from pointing fingers.

It would be easy to lump Battle Royale in with other violent films of the noughties, particularly the rise of torture porn, but that would be to denigrate a film that takes a real interest in its characters and draws from the director’s own experiences of the Second World War. Kinji Fukasaku, best known to Western audiences for his work on Tora, Tora, Tora (1970), took on the film at the age of 71, in part because it took him back to his work in a weapons factory when he was a teenager:

During the raids, even though we were friends working together, the only thing we would be thinking of was self-preservation. We would try to get behind each other or beneath dead bodies to avoid the bombs. When the raid was over, we didn’t really blame each other, but it made me understand about the limits of friendship (Rose 2001).

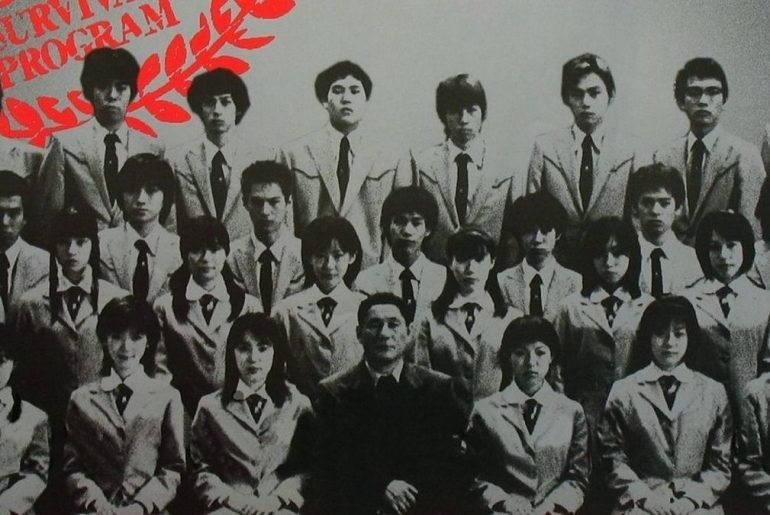

The limits of friendship are tested throughout as the students of class 3-B are each given a bag of supplies, a weapon, and 3 days to kill each other. Battle Royale takes place in a vaguely futuristic Japan where, after an economic crisis, youth is seen to be running wild. The government’s response, the BR Act, selects a single class from across the country (supposedly at random) and places them in a remote location. Only one of them is allowed to leave. To ensure their compliance each student is fitted with an explosive collar; if they step out of line or if more than one is alive at the deadline their throat explodes.

Although the film mostly follows the rather sweet couple of Shuya and Noriko, Fukasaku takes care to give as many of the students a sense of character as possible. This is expanded in the Special Edition in which the previously psychotic Mitsuko is given a back story that partly explains her character (an incredibly creepy sequence in which she is sold, as a little girl, by her mother to a paedophile whom Mitsuko then kills by accident). This emphasis on character shows a care for the students that lifts them from being cannon fodder. Some are resourceful, some are terrified, some are desperate to lose their virginity before death, but none are identical. It pushes back against the typical view of teenagers as a homogenous mass that threaten society. Indeed, the film clearly suggests that the teenagers are no worse than the culture that created them.

Shuya has been let down by his parents (an absent mother and a father who killed himself, Shuya finding the body), but he shows great resourcefulness and loyalty. Contrast him to the teacher Kitano (played by director ‘Beat’ Takeshi Kitano) who runs the Battle Royale – his life is in tatters: he is alienated from his wife and daughter, and has grown to hate his former class, and the young in general, for making him feel impotent (all except Noriko, for whom he has an unhealthy obsession). It’s a terrific performance by Kitano, which plays on his dual status as director of violent films and game-show host. He is almost impassive throughout only hinting at the inner frustrations his character is riven with, becoming so petty he refuses to share some cookies he swiped from Noriko with the military officers who run the “game”.

Seen very much as a satire on the highly competitive Japanese education system on release the film exposes what happens when people are pitched against each other for crumbs. Of course, inevitably, the game is rigged with two ringers brought in to stack the deck against the students. Just like life, lip-service is paid to fairness, but the reality is far from it. When I first watched the film, when it was released in the UK in 2001, it seemed like a pretty dark and remote vision of how schools could become competitive production lines designed to stifle young-people and scare them into conforming. Having been in teaching for 12 years now it seems much less ridiculous. Reforms to the education system in England are leading to a rise in mental illness in students and one teacher’s comment that “I have at least one student who has attempted suicide, and others with a variety of mental health issues” (Busby) is becoming alarmingly typical, and something I’ve witnessed on a local level. This extends to UK universities where “the suicide rate among UK students had risen by 56 per cent in the 10 years between 2007 and 2016, from 6.6 to 10.3 per 100,000 people” (Rudgard).

An economic crisis followed by an increasingly cut-throat and competitive education system that pits young people against each other in which they are made to feel that their very lives are at stake? Battle Royale is now closer to reality than I find comfortable.

Works Cited

Busby, Eleanor (2018) Pupils self-harm and express suicidal feelings due to exam stress and school pressure, warn teachers. The Independent [online]. Available at https://www.independent.co.uk/news/education/education-news/school-pupil-mental-health-exams-school-pressure-national-education-union-neu-a8297366.html

Rose, Steve (2001) The Kid Killers. The Guardian [online]. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/film/2001/sep/07/artsfeatures2 [accessed 27/07/2018]

Rudgard, Olivia (2018) Universities have a suicide problem as students taking own lives overtakes general population. The Telegraph [online]. Available at https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/04/12/universities-have-suicide-problem-students-taking-lives-overtakes/ [accessed 27/07//2018]

Comments are closed.