A few years ago I had the pleasure of speaking at the American New Wave: A Retrospective conference at Bangor University organised by Greg Frame and Nathan Abrams. After the conference finished a call went up for contributions developed from the papers and lo and behold the time is coming when this work will be released. Due to be published on 21st October 2021 by Bloomsbury Academic, New Wave, New Hollywood: Reassessment, Recovery and Legacy collects a series of essays that hope to re-evaluate some of the key ideas and theories that dominate our views on the period and includes my thoughts in Chapter 3 ‘Formal Radicalism vs. Radical Representation: Reassessing The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971) and Dirty Harry (Don Siegel, 1971)’. It’s a bit intimidating to be in such esteemed company, and not to mention rather exciting, but I’m sure I’ll keep my feet on the ground – as Harry Callahan reminds us, ‘A man’s got to know his limitations’.

This paper was originally presented to London Film & Media 2011, and published in The London Film and Media Reader 1.

The Vigilante Thriller

This essay considers the condemnatory and heavily ideological critical reactions to a cycle of US vigilante thrillers from the 1970s. The cycle includes Straw Dogs (Peckinpah, 1971), The French Connection (Friedkin, 1971), Dirty Harry (Siegel, 1971), Death Wish (Winner, 1974) and Taxi Driver (Scorsese, 1976). A common accusation was that the films were ‘fascist’, made by ‘fascists’, or liable to encourage ‘fascism’ in the film audience. This was not a label that was necessarily rejected by all the film-makers – certainly Sam Peckinpah enjoyed baiting reviewers and interviewers with a series of abrasive, and often, contradictory statements – but the consistency of this criticism highlights an anxiety in the critical reactions about the meanings of these films and, on closer inspection, the meanings of the violence they portray.

Although the critical writings are an important reaction to the texts, discourse analysis reveals a series of inconsistencies and contradictions in their assumptions about the ways in which a film can be watched. Rather than relying on these critical responses alone to guide us in terms of spectator reaction, we should instead be analysing what Ellis terms the ‘narrative image’,

“an idea of the film [that] is widely circulated and promoted … the cinema industry’s anticipatory reply to the question ‘what is this film like?’” 1

It is important to investigate how this element of para-text fixes, or aims to fix, the spectator’s experience, since the narrative image is also essential in fixing the modality of the film text. Following Hodge and Tripp, ‘modality’ is being used here in the sense that it “concerns the reality attributed to a message.”2

This has specific implications for the reception of film violence, and it is the understanding of violence that I wish to concentrate on in this essay. These distinctions were missed by contemporary critics, who ignored the concept of modality, tended to see film violence as a singular issue, and recycled basic tropes about the effect that film violence might have on the audience. Despite the consistency of the critical reaction to these films, the narrative image of each film suggests a range of spectator positions. The desire to elide these films on the part of contemporary critics, on the other hand, signals a wish to simplify the spectator experience and ignores the shifting relationship that a spectator can have in relation to several connected but different texts.

Critical Reactions: The Politics of Violence

Even a cursory glance at the American and British popular press reaction to these films reveals two central concerns, both of which are linked to the possible effect of the films on the audience and the wider implications for society. The first concern, highlighted more by the American critics than the British, is the suggestion that these films convey and promote a fascist sensibility. The second concern, which is present on both sides of the Atlantic, concerns the portrayal of violence. This is often linked to a perceived increase in the amount of violence being portrayed in film, the explicitness of the violence, and the sense that the films in question encourage the spectator in turn to be violent.

Pauline Kael’s critical reaction to the films exemplifies the general tone of the reviews. For Kael, Straw Dogs is a “fascist work of art”3 that presents the “triumph of a superior man”. Dirty Harry is a “right wing fantasy” that attacks “liberal values” and draws out the “fascist potential” of its genre4. The French Connection, for its part, features “the latest model sadistic cop”5. Gareth Epps draws wider conclusions from Straw Dogs, The French Connection and Dirty Harry such as

“it has been obvious for a long time that American filmmakers are unable to deal with the politics of the left in any recognizable way”6 .

These films, he suggests, are symptomatic of a wider right-wing tendency in Hollywood. He adds that “recent American films have begun to show a frightening sophistication in at least one area of politics – the half-world of sadism and authoritarianism which is the breeding ground of the fascist mentality”. The accusation that the films are characterised by ‘fascist’ ideology betrays an anxiety in the reviewers towards the shifting political landscape in America through the 1960s and into the 1970s.

The effects of the Vietnam War on the collective American consciousness cannot, of course, be ignored. However the shifts in civil rights movements, crime and policing are also important here. The elements that were picked out from these films and directly linked to fascism included the representations of masculinity, race and violence. From a didactic point of view, however – and many of these reviews and reactions were written in a didactic mode – there is a recurrent flaw, namely an inability to define exactly what fascism is. Its recurrent use as a blanket term in reaction to these films shows a remarkable inconsistency in its application, and also a sense that the word is being used as a short-cut, a way of marking a text as unacceptable, with no underlying understand of the word and its political/philosophical application.

Critical Reactions: Violence and Spectatorship

If fascism is one recurrent way of condemning these films, the other anxiety that emerges is the meanings and implications of violence in the films. As has been noted elsewhere, the depiction of violence in American cinema changed radically in the 1960s and 70s. There are various reasons for this, including the influence of non-American films, and the eventual dissolution of the Hays code. More important perhaps was the shift in the representation of violence on television where, from the shooting of LeeHarvey Oswald by Jack Ruby to the reports from the front line in Vietnam, violence was being shown more often and more explicitly.

Of course this form of violence, presented in news programmes, has an inherently high modality despite its mediated nature. In this atmosphere of a shifting depiction of violence, combined with a greater perception of violence in society through rising crime rates and civil unrest, the implications of watching – and more importantly enjoying – film violence became a point of anxiety for contemporary critics. The reviews of Taxi Driver generally avoided the same ideological criticism as the other films and one wonders if this is linked to the potential audience for such a film. Kael suggests, in reviewing The French Connection, that

“Audiences for these movies in the Times Square area and the Village are highly volatile. Probably the unstable, often dazed members of the audience are particularly susceptible to the violence and tension on the screen”7.

It is clear that a strain of elitism has entered the critical reaction here.

The New York Times felt the need to send reporter Judy Klemesrud to a theatre to gauge reaction to Death Wish, asking “What do they see in ‘Death Wish’?”. Klemesrud interviewed audience members and “Three mental health professionals” in the course of her quest.8 I think it’s important here to highlight the suggested opposition in that headline – “they” are clearly not “us”, “us” referring to those sophisticated enough to read the New York Times. Across many reviews and articles on both sides of the Atlantic there is a clear fear concerning the possible impact of a text on a supposedly less sophisticated audience.

These reactions were not without their contradictions. Charles Barr, for instance, noted the differences between the British critical reaction to Straw Dogs and A Clockwork Orange (Kubrick, 1971). 9 His conclusion, that the reaction differed because of the way in which violence was presented by each film – for example, by the use of telephoto lenses in Straw Dogs compared to the use of wide angle lenses in A Clockwork Orange – signals the inconsistency in the criticism of films marked as violent.

Stylistic distinctions are then critical, Barr argues, for understanding the ways in which the films operate: Minute-for-minute, A Clockwork Orange contains more instances of violence than Straw Dogs, but Straw Dogs does not allow the spectator the luxury of remaining distant through the use of the wide-angle lens. The fear of what Straw Dogs implied for cinema and the audience nonetheless moved thirteen British critics to write to The Times to decry the film’s certification, expressing their “revulsion” at the film and its marketing.10 In other reactions we see a clear perceived link between the film text and possible audience reaction (The Guardian, for example, felt strongly enough to send a reporter to New York to examine how Death Wish was inspiring American traditions of gun ownership).

The underlying fear in many of the critical reactions was that the audience, having watched the film, would themselves become vigilantes. That the critics themselves didn’t burst out of auditoria and beat up some muggers seems to have escaped their attention. Moving away from the discourse concerning the supposed effects of film violence we also encounter an inconsistency among critics to accurately differentiate between different types of violence, an inability to recognise the difference between the nature of the act being represented, and the method of its representation.

Modality and Narrative Image

The elision that the contemporary critics made between these films ignores the importance of the narrative image in conditioning the modality of the spectator’s engagement. Even if we acknowledge the polysemic nature of film texts and their para-texts, dominant themes from the marketing of the films suggest ways in which the spectator is primed to watch and respond to a text. The narrative image tells us the frame of mind in which a spectator receives a film; this in turn suggests a level of modality in which the spectator will receive the film violence. To suggest that all film violence can be measured the same way is to ignore the differing modalities of films. In short, not all film violence is equal.

The decision the spectator makes about whether to watch a film will often rest on several factors. One of the key elements is the marketing and promotional material of the film. When examining these for each film we see that they suggest several different ways in which to receive and understand the violence of the films, something typically ignored by the critics. We may thus conceive of the spectator as having a personal and private relationship with a film that takes place within the cinema, but we should also acknowledge that the spectator’s experience of the film begins with several para-textual factors that help condition their subsequent experience.

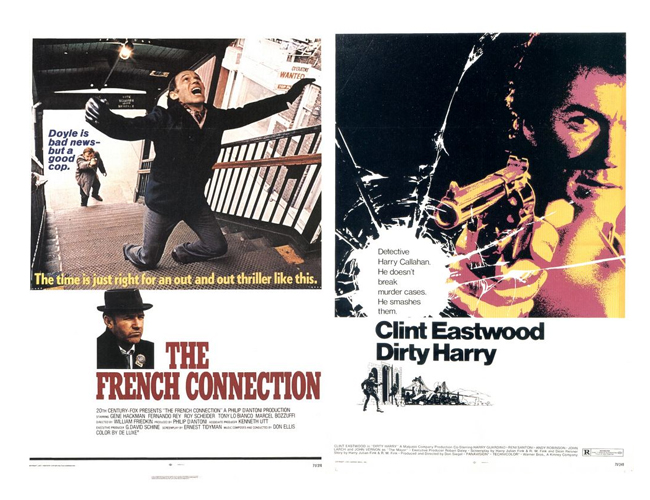

Take, for instance, the use of violence in the poster imagery for the films. Straw Dogs, whose central image is a close-up of Dustin Hoffman with one lens of his glasses broken, signals violence, but also the effect of violence on the protagonist. The French Connection uses a still of ‘Popeye’ Doyle shooting a suspect in the back as its main image. Dirty Harry concentrates on the persona of Clint Eastwood (but also the duality between the two main characters), while Death Wish uses the image of Charles Bronson. Taxi Driver’s central image, of a lost and isolated Travis Bickle posed in front of a New York street scene locates an alienated figure in a world of degradation.

This image for Taxi Driver places the spectator in a very different relationship to the violence of the text than the other posters. By not signalling the violence but concentrating on the alienation of the protagonist (in effect hiding the violence), the poster prepares us for a film where acts of violence, when they do occur, have greater weight. The casting of De Niro (still relatively unknown at this point and thus ‘absorbed’ by his role in the film), and the setting of the film in real areas of New York, confer a high modality.

This is reinforced by the presentation of the violence in the film. This is not expected in the same way as in an Eastwood or Bronson film, where violence is an inherent part of the experience. Indeed the marketing of both Dirty Harry and Death Wish so connects the characters to their actors as to create a direct intertextual link to their other films. In these circumstances film violence becomes a ritualised part of the cinematic experience. The French Connection, however, with its concentration on reality, linked to the oft-repeated information that the film was based on real events, suggests a higher modality for the film violence which it contains.

We are watching here a reproduction of real violence, not the heightened and stylised violence of an Eastwood or Bronson film. The ritualisation in Dirty Harry and Death Wish confers a lower modality on the violence, which has become part of the expected generic formula of the text, an inevitable and unsurprising element. Through its enigmatic title and ambiguous central image, on the other hand, Straw Dogs denies the spectator a secure sense of how violence will operate in the film.

Generic Contexts

The explicitness (or lack) of generic context creates other issues here. It has been noted, for instance, that both Dirty Harry and Death Wish bear relation to the Western film, in casting (the stars of both had previously appeared in successful Westerns), iconography and structure. Perhaps the relocation of the generic elements to a modern day location, stripping away the mythic trappings of the narrative, creates this discomfort around the violence.

The recognition of Western genre conventions in the narratives of Dirty Harry and Death Wish may confer a different level of modality than a film such as Taxi Driver, which has a less clear generic definition. The ritual of genre, the procession of structural and iconic elements, reminds the audience that what they are watching is a structured creation – when it runs true to form, the text offers much reassurance but little by way of surprise. This, I would propose, effectively lowers the modality.

Too often film violence is taken out of the context of reception. Film violence occurs within several frameworks, including the textual implications of narrative and genre. The narrative image of a film is explicit in its attempts to set up these elements for the spectator. Thus the debate about film violence should be embedded in not only the referential and aesthetic components of film violence, but also in analysis of the place that violence has within the contextual, paratextual and textual experience of the film. For contemporary critics of these films however, socio-political concerns of the day outweighed the specifics of the textual/para-textual experience.

Notes and References

1 John Ellis, Visible Fictions: Cinema, Television, Video, London: Routledge, 1982, p. 30.

2 Bob Hodge and David Tripp, Children and Television, Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers, 1986, p. 104.

3 Pauline Kael, Deeper into Movies: The Essential Collection, from ‘69 to ’72, London: Marion Boyars, 1975, p. 398.

4 Kael, Deeper into Movies, p. 385.

5 Kael, Deeper into Movies, p. 316

6 Gareth Epps, ‘Does Popeye Doyle Teach Us How to be Fascist?’, The New York Times, 22 May 1972, II:15, p. 1.

7 Kael, Deeper into Movies, p. 316.

8 Judy Klemesrud, ‘What do they see in Death Wish?’, New York Times, 1 September 1974, II:1, p. 5.

9 Charles Barr, ‘Straw Dogs, A Clockwork Orange and the Critics’, Screen, vol. 3 no. 2, 1972, p. 23.

10 Fergus Cashin, John Coleman, N. Hibbin, Margaret Hinxman, Derek Malcom, George Melly, T. Palmer, J. Plowright, Dilys Powell, David Robinson, John Russell Taylor, Arthur Thinkell, and Alexander Walker, ‘From Mr. Fergus Cashin and Others”, The Times, 17 December 1971.

One of them is a loner who gets thrown every dirty job in town. His solution: shoot his .44 Magnum and damn the consequences. The other is a blue-collar roughneck, a porkpie-hat wearing boot fetishist as likely to shoot a colleague as he is a bad-guy. Welcome to 1971. Welcome to the birth of the modern action hero. It wasn’t a smooth delivery. The critics reacted with catcalls of “fascist”. Roger Ebert wrote, “if anybody is writing a book on the rise of fascism in America, they ought to take a look at Dirty Harry”. Garrett Epps of The New York Times asked “Does Popeye Doyle Teach us to be Fascist?”, deciding no, but that The French Connection is a “celebration of authority, brutality and racism” (which sounds pretty fascist to me). Dirty Harry on the other hand “is a simply told story of the Nietzschean superman and his sado-masochistic pleasures”. Pauline Kael, never a fan of Eastwood, described Dirty Harry as a “right wing fantasy” and The French Connection as featuring “the latest model sadistic cop”. Vincent Canby, also in The New York Times, decried Dirty Harry with the criticism, “I doubt even the genius of Leni Riefenstahl could make it artistically acceptable”. Something about these films got up the nose of American critics. Perhaps this was only made worse by their popularity with audiences. But how did early 70s cinema come to embrace these men, and the McClanes, Riggs and Cobrettis to follow?

Looking back over the history of cinema two types of film dominated action before 1971; the western and the war film. It all changed, in the 1960s as the cops began to take over. They brought the action into the city, finding a new wilderness among the streets and the neon lights. Cities became the new frontier, dark, shadowy and fuelled by drugs. It reflected the changes in American society; the huge rises in crime, particularly mugging, had Americans scared to walk city streets. This was a different America and it needed different heroes. The French Connection and Dirty Harry redefined how America’s heroes would look and act, casting a shadow over action cinema for a generation to come. The story goes that 1960s cinema ended in counter-culture revolution. Led by Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967), The Graduate (Mike Nichols, 1967) and Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper, 1968) the audience found themselves on the side of the law-breakers, railing against society, whether it be the cops, the banks or the politicians. Take a closer look and another, parallel, story comes clear. The success of films like The Dirty Dozen (Robert Aldrich, 1967) and Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy, alongside the earlier, harsher Bond films, showed that there was an audience for tough heroes. What was different about them was how they abandoned the codes of the past – these guys were selfish, in it for themselves, often only doing the right thing incidentally. These weren’t the classic heroes of the past, the sort that Joseph Campbell wrote about. They were anti-heroes, the dark shadows of heroism. Ever since WW2 heroes had been getting darker, as if the horror of human behaviour exposed in Europe and the Far East had leached out the possibility of anybody being truly good. Even John Wayne got in on the act in The Searchers (John Ford, 1956). It’s difficult to imagine now because, by and large, today all movie heroes are anti-heroes. Go back to the 1940s and watch Errol Flynn or James Stewart and see men who do right because it’s right to do it. As American life got more complicated, with conflict at home and abroad, it became harder and harder to find purity in anyone’s motives. It would get worse before the 60s was out.

Charles Whitman climbed a tower at the University of Texas in Huston in August 1966 and started shooting. He killed 14 and wounded 31 before the Police shot him. The shadow of the Zodiac killer settled over San Francisco in the late 1960s as he taunted Police with his letters. He was never found. And in 1969 Charles Manson’s ‘family’ broke into 10050 Cielo Drive murdering, among four others, Sharon Tate, pregnant actress and girlfriend of Roman Polanski: all three helped signal a change. Nobody was safe anymore, not even Hollywood stars. It was the final nail in the coffin of 60s optimism. All the leaders, Kennedy and King, were dead. The movie heroes of old didn’t cut it (just watch Wayne’s self-directed Green Berets (1968) or Brannigan (Douglas Hickcox, 1975) for evidence). America needed new symbols to help it feel safe at night. Cue Jimmy ‘Popeye’ Doyle and ‘Dirty’ Harry Callahan, although in many ways The French Connection and Dirty Harry couldn’t be more different. The former was directed by a precocious young director from TV noted for several art-house style films, the latter made by one of Hollywood’s old hands, who could trace his career back to Hollywood at its peak in the 1930s and 40s. But what both William Friedkin and Don Siegel understood was that the time was ripe for a new, tougher, more cynical hero.

Friedkin had been circulating for several years in Hollywood and had been tipped as a hot director. He mastered his craft making documentaries on the streets of his home town Chicago, working areas other film-makers wouldn’t touch like the black South-Side. He was an abrasive young man, supremely talented, directing for TV in his early twenties. Siegel began at Warner’s back when the Studio System was in its heyday. He began in the Film Library Department, moving through the company to Editorial and Insert departments. Here he contributed to some classics like The Roaring Twenties (Raoul Walsh, 1939) and Confessions of a Nazi Spy (Anatole Litvak, 1939). He worked with such greats as Michael Curtiz (director of The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) and Casablanca (1942)) and Howard Hughes, eventually graduating to directing at Hughes’ RKO. The movie he will always be remembered for, other than Dirty Harry, is Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1962), regularly cited as the best B-movie ever made. An efficient director, Siegel worked quickly and effectively. He shot what he needed, scouted his own locations and liked to collaborate. He was just the sort of director Clint Eastwood appreciated. By 1970 Friedkin’s career was stalling. He was making movies, dramas such as The Boys in the Band (1970), but his films weren’t making any money. That would all change after an encounter with Howard Hawks. “People don’t want stories about somebody’s problems or any of that psychological shit”, Hawks told him, “What they want is action stories. Every time I made a film like that, with a lotta good guys against bad guys, it had a lotta success, if that matters to you”. It mattered to him alright. His next film was The French Connection.

Siegel and Eastwood first met on Coogan’s Bluff (1968), an early attempt to translate Eastwood’s Spaghetti Western success to America. It worked, with Eastwood starring as an Arizona lawman relocated to New York to extradite a suspect. It featured some brutal action, including a great bar fight. Coogan’s single minded pursuit of hippy suspect Ringerman, and willingness to ignore regulations, served as a prototype for Harry. With Dirty Harry they were able to create a purer distillation of the action formula from Coogan, dumping the unnecessary love interest, turning the conflict between Harry and Scorpio into the focus. Watch Harry again and it might even seem that the sado-masochistic relationship between cop and killer is its own sort of twisted romance, camera flying away from the stadium to protect their privacy when they are finally alone. The producer of The French Connection, Philip D’Antioni, previously brought Bullitt (Peter Yates) to the screen in 1968. Inspired by real events, and the book by Robin Moore, The French Connection provided a chance to repeat the earlier success. For that purpose he demanded one thing from Friedkin, a car chase to beat the one in Bullitt. Both the chase and its filming are now legendary but are just one part of a film which constantly innovates and defies convention. Filming in a down and dirty documentary style, casting a character actor, Gene Hackman, in the lead, allowing cast to improvise (a cast which included real life “Popeye” Eddie Egan as Doyle’s boss), and taking cues from The French New Wave, The French Connection is like nothing else produced in Hollywood at the time. It’s also groundbreakingly violent. Just witness the car-crash victims; they’re nothing to do with the plot but Friedkin lets his camera linger over the mess of their bodies. Then think about that final shot. What other Hollywood film leaves the audience with such a bleak and unresolved ending, Doyle charging off into the darkness having shot one of his own colleagues?

You can see how real life events influenced Dirty Harry. Check out Scorpio and you can see the influence of Manson, the Zodiac killer and Whitman; Scorpio represented everything that was going wrong with America, and he could even have been a returning Vietnam veteran with his military boots and rifle proficiency. Those who read Callahan as an authoritarian figure taking on a hippy loner miss the point, though. Yes Scorpio is all that’s bad but Harry’s not much better. As the film plays out, a teasing parallel between Scorpio and Harry emerges, they’re both voyeurs, both loners, both killers. Their combat is a dance to the death across the streets of San Francisco. That late 60s anti-authoritarian streak runs through Callahan and Doyle and shows that these films have more in common with the Easy Riders of this world that you might think. Both are fierce individuals, outsiders who don’t fit in to society – but the difference is they’re there trying to make it work. Both films hinge on their heroes. They’re a strange pair, both loners paired with partners whose normalcy only highlights their extremes, both isolated by society. Friedkin pulls no punches in his depiction of Popeye as a slovenly, driven and violent man. Watch the scene where Frog One, Charnier, enjoys a three course meal while Popeye stands outside drinking stale coffee and eating greasy pizza. It’s a wonderful evocation of the thankless task that stands before the police; the street smart blue-collar worker living in a small apartment that resembles a prison cell versus the urbane French charmer with a house on the Riviera. Dirty Harry‘s opening shots, hovering over a memorial board to San Francisco police men points to the danger and thanklessness of the task. In some senses they’re the reincarnation of the Western hero dragged into the city, the lone gunman dealing with injustice. But in the city their actions provoke outraged responses, the cushion of myth having been removed. Just like Will Kane in High Noon (Fred Zinnemann, 1952), who like Harry throws his badge away, they’re abandoned by the townsfolk and have to do what’s best on their own.

Initial reaction to both films was fierce, many critics highlighting the violence, but Dirty Harry was by far the most kicked about. Harry’s perceived racism was a particular bone of contention, despite the fact that he has friends and enemies of different races. Both Siegel and Eastwood have been on record defending the films from such accusations. In his autobiography, A Siegel Film, the director described his approach, “If I do a film about a murderer, it doesn’t mean that I condone murder. If I do a film about a hard-nosed cop, of course it doesn’t mean I condone all his actions. I find it very difficult to explain my reasons for making a film like Dirty Harry, other than I’m a firm believer in entertainment, hoping that every picture make will be a commercial success. Not once throughout Dirty Harry did Clint and I have a political discussion.” Similarly The French Connection found its critics, suggesting the film to be racist and authoritarian, but it also registered far more supporters. It was a huge box-office success ($30million plus in the US alone) and won five Oscars, including best director. Dirty Harry won no awards, but took over $28 million and cemented Eastwood’s star status. The impact of these two films still resonates through their sequels and imitators. As Eastwood proved in Gran Torino (2008) he has never really escaped the shadow of Callahan. The lone cop, the disregard for superiors, for red tape and rules, the brutality of the violence; these can all be seen in modern action movies. Check out the rivalry between John McClane and his slick European rival, Hans Gruber, in Die Hard (John McTiernan, 1988); it clearly echoes Doyle and Charnier. What is Riggs but Callahan pushed to his logical, suicidal extreme? How about that scene in Lethal Weapon (Richard Donner, 1987) with the jumper? Straight out of Dirty Harry. Come to think of it aren’t both Die Hard with a Vengeance (John McTiernan, 1995) and 12 Rounds (Renny Harlin, 2009) just two hour remakes of the phone chase in Dirty Harry? Look at any cop-thriller or action film from the 1980s or 90s and the influence of Doyle and Callahan is clear. Fascist Super Cops? No. Fascists aren’t free thinkers, they don’t possess the cynical edge of these men, the individuality. The critics saw the violence, but missed the point. The audience got it. And we’re still getting it today.

From its early days cinema has showcased violence.

Whether it was boxing matches or recreations of historical events violence has been infused into the very nature of the medium. If we believe the old story about the Lumière Brothers scaring their Paris audience the beginning of Cinema was a violent act in itself. With this presentation of violence came politics. Perhaps it was the accessibility of cinema that made it open to more political interference than literature or theatre (although these were also messed with), the fear that the plebs, who wouldn’t/couldn’t read or understand high culture, would be corrupted by this new form. Early on movies were being banned for their violence, but sometimes the reasons were as much politically motivated as out of a ‘duty’ to protect the masses; in the US one early boxing film was banned on racial grounds, as it showed a black boxer beating a white boxer, undermining the ‘inherent’ superiority of the white race.

The dominant discourse on violence today remains rooted in the spurious effects debate. Every so often a film is seen to be the cause of society’s ills, or it offers the potential to corrupt and degrade. A cursory glance at the history of Hollywood film offers a list of titles that have been suggested as, but never proven to be, the inspiration for real acts of violence. Films such as Rebel Without a Cause, Taxi Driver, Natural Born Killers, Scream, Child’s Play 3, not to mention the litany of 1980s Video Nasties have been implicated. But this debate fundamentally lacks an understanding of the complicated ways in which the audience experiences film violence. In this article I’ll outline some of those ways, in the hope that we can move the debate a little further from the purview of the Daily Mail.

Before, During, After

The paratext are the texts that surround and inform any individual text. Generally speaking we don’t watch movies in a vacuum, particularly now as we’re constantly bombarded with trailers, posters, websites and even trailers for trailers. These elements, also known as the Narrative Image, inform and mediate our responses to cinema, including how we understand the violence. In short our experience and understanding of film violence occurs before (paratext), during (spectating) and after the film (in the ways we remake the film in our memories, how they compare to other texts, etc). Beyond these paratextual elements are the social and political contexts that inform the text and our responses. To give a brief example most film students are forced to watch the Odessa Steps sequence from Battleship Potemkin (Sergei Eisenstein, 1925). But the context of watching this in the 21st Century, in Europe, can’t match the context of post-revolutionary Russia, or interwar Britain where the film was banned. Our approach to the film is framed by these paratextual elements of expectation where a genre, title or star, can confirm or subvert.

Generic and narrative expectations are another major part of this experience, elements which are, by and large, set by the narrative image. The Western is a genre that depends on violence – the narrative is organised around the final shoot-out, the showdown between protagonist and antagonist. It would be ridiculous to watch a mainstream Western then and be surprised by the violence in the final scenes. The emotional response to such a moment is therefore conditioned by expectation. Films that muddy the generic/narrative waters generate different responses. Take the violence in Pan’s Labyrinth (Guillermo Del Toro, 2006). The film is framed as a fairytale of sorts, in which a small girl (evoking characters like Alice), explores a world of fantastic creatures. Then a man has his face bashed in with a bottle. Nothing in the narrative/genre has suggested this event, the impact is greater.

These elements of genre/narrative and paratext also condition the modality of the films. Modality is the level of reality that we ascribe to a message. For instance the News has a higher modality than Tom and Jerry; one presents itself as a true representation of reality, the other is a cartoon in which impossible events occur. Films generally exist somewhere between these two extremes. A film that employs documentary style camera work conveys a higher modality than one that involves impossible CGI shots. Similarly the advertising of a film can stress fantastic or realistic elements. Early coverage for The Blair Witch Project presented the film as true, that the footage had been recovered. For those early audiences the film had a high modality, creating a different response to later viewers who watched is as part of the normal horror genre.

Elements of Film Violence

If our approach to film violence is conditioned before we even sit in the cinema what then of the films themselves? One cannot hope to fully elucidate the complexities of this in a short essay, but I can outline a few significant elements.

Prince (1998) breaks film violence down into three elements; the referential act, the stylistic encoding and the stylistic amplitude. The referential act is the act of violence that the film depicts. Our understanding of this is complicated in itself. Has the audience experienced this act themselves, or seen it before in other films and media? Each act of violence in a film is seen in comparison to other films and the real world. Increasingly the violence we see bears no resemblance to our life experience – our referent becomes other films. The stylistic encoding is how the referential act is depicted in the film, the shots used, the sound, etc. Take for comparison the finales of High Noon (Fred Zinneman, 1952) and Dirty Harry (Don Siegel, 1971). In High Noon the hero, Will Kane, shoots the villain Frank Miller with a single bullet. It takes 5 seconds of screen time and is shown in a single shot from where Kane stands, leaving Miller in the background. When Harry shoots Scorpio over 8 single shots are shown, taking just over a minute of screen time. When Scorpio is hot we see, from multiple angles, him thrown backwards, blood spurting from his body; the same referential act, encoding in two very different styles.

The final aspect, the Stylistic Amplitude, covers ideas of graphicness and duration of the encoded act. In essence the more graphic the depiction the greater the duration. The more of the violence we see the more significant it is in the film’s running time. As a general trend in Hollywood cinema more time is given over to violence in movies.

Positioning the Audience

As a final issue we need to consider how the film positions its audience in relation to the characters that enact violence. There are two positions available, one subjective (we watch/follow/align with a character(s)), the other objective (we are not aligned with anyone, we watch separate from the action). This makes a big difference in how we relate to a film. The subjective camera, using shots like point of view, implied point of view and over shoulder, invite us to partake in the violence. Narrative techniques, such as narration, further encourage our identification with characters and violence (a good example of this is Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976)). The objective camera keeps us at a distance, although we still align with a protagonist through convention, leaving our involvement as less participatory.

In Conclusion

Moving the discussion about film violence away from the tabloid headlines and towards a technical understanding of cinema and its audience is essential if we’re ever to puzzle out how and why people watch violent films. If we can do that we may be able to finally kill off the histrionic exaggerations, with or without the use of a shotgun.

Works Cited

Prince, Stephen (1998) Savage Cinema: Sam Peckinpah and the Rise of Ultraviolent Movies. Austin: University of Texas Press