Bangor University – 7 & 8 September 2023

I had the great pleasure to return to Bangor University recently at participate in the Paul Verhoeven@85 Conference – a great set of panels discussing the works of a rather neglected director. Organised by Professor Nathan Abrams and Doctor Elizabeth Miller the conference covered all of Verhoeven’s three distinct periods, the early Dutch films, his move to the US, and his return to European filmmaking, and took a wide range of approaches, including looking at philosophy, politics, ideology and some interdisciplinary talks that covered Special Effects, Amputation and the ethics of public and private health care. My contribution, Bodies of Steel, Bodies of Mush: The Hard Body and Paul Verhoeven’s Dystopian Science-Fiction Action Films, discussed how RoboCop, Total Recall and Starship Troopers all subvert Susan Jeffords’ conception of the hard-body action film. Keep reading for the transcript.

Introduction

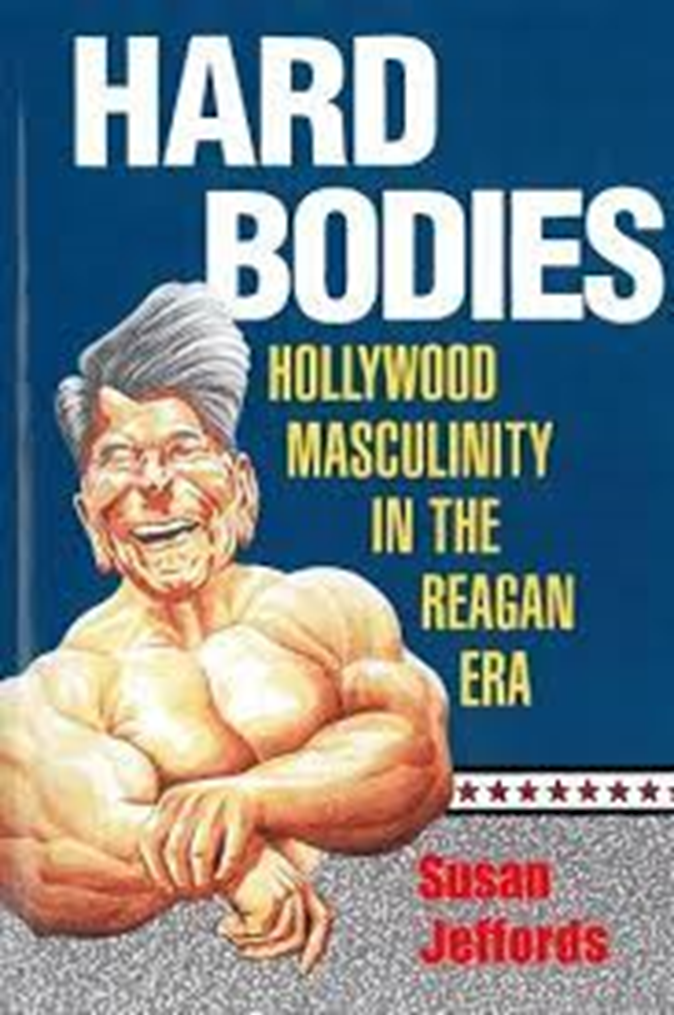

Richard Nixon, writing in his 1980 book The Real War, raised the question of whether the United States would be a nation of ‘steel or mush’. Condemning the outgoing Carter administration particularly, and the whole US more broadly, Nixon called for leaders who are ‘”steely”, resolute and certain’ as opposed to those he called ‘”paralyzed”…, uncertain, “mushy” and wavering’[i]. The work of Susan Jeffords saw a link between the rise of what she coined the hard-body Action Film with the rise of a steelier version of American masculinity, encapsulated by the election in 1981, and re-election in 1984, of Ronald Reagan. As Jeffords states, ‘Ronald Reagan became the premiere masculine archetype for the 1980s, embodying both national and individual images of manliness that came to underline the nation’s identity during his eight years in office’[ii]. This masculinity, one which was ‘tough, aggressive, strong and domineering’[iii] counteracted the perceived weak and feminine Carter years (and Hollywood’s cinema of crisis and doubt evident during the New Wave period) and was encapsulated by the figures of Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone. This new hyperbolic masculinity, defined not only through action but through the prolonged gazing at the stars’ musculature, would place the hard-body at the centre of the 1980s box-office, establishing Stallone, Schwarzenegger (and a select few others) as among the top stars in America and around the globe.

The growing American confidence of the Reagen era was reflected in the confident and decisive actions of the hard-body Action Heroes, such as when Stallone, as John Rambo, returned to Vietnam to demonstrate the American Soldier’s superiority in Rambo: First Blood Part II (George P. Cosmatos, 1985), or when Rocky Balboa, Stallone again, put the ‘Evil Empire’ of the USSR in it’s place in Rocky IV (Sylvester Stallone, 1985). The hard-body hero is a hero of overt, muscular, physical display, ritualized suffering, and movement which became synonymous with America itself (even when represented by the heavily accented immigrant Schwarzenegger). Rooted in the freedom of the individual the hard-body hero fights not just threats foreign and domestic, but also the limits of government bureaucracy (mirroring Reagan’s Small Government policies). As Jeffords summarises, these are movies with ‘spectacular narratives about characters who stand for individualism, liberty, and a mythic heroism’[iv].

These are films that offer their spectators a sense of mastery, in terms of plot ‘in which the hard-body hero masters his surroundings, most often by defeating enemies through violent physical action; and at the level of national plot, in which the same hero defeats national enemies, again through violent physical action’[v]. Spectators vicariously experience the hero’s power through identification both on a personal level, and as a collective in that the hard-body embodies the ‘political, economic, and social philosophies’ of the Reagen era.[vi]

This paper discusses how Paul Verhoeven’s Action Science Fiction films, RoboCop (1987), Total Recall (1990) and Starship Troopers (1997) interact with, reconfigure and parody this conception of the Hard Body. The first two of these films are regularly seen as part of the Hard Body movement and I will suggest that rather than conforming to the Hard Body formula, both films explore, expose and critique the very idea of the Hard Body. The third film, made after the Reagan period and post the box office dominance of the Hard Body Action film, builds on the themes from the previous two films but goes further in exposing the hollowness of the Hard Body concept – all three films demonstrate the tenuousness of the Hard Body, but also draw attention the anxieties the Hard Body formula represses. Rather than reinforcing the hardness of the Hard Body, Verhoeven’s films remind us consistently of the mush that sits within the hard shell, that the body’s essential fragility is inescapable and that the political associations of individuality and freedom are illusory. The construction of the Hard Body is drawn attention to, and the spectator’s sense of mastery is subverted – particularly through the repetition of images and themes of lobotomy, a mushy brain.

Part One: Total Body Prosthesis.

1987’s RoboCop was Verhoeven’s first American film and it is broadly recognised as a satire on many Reaganite policies, particularly the use of the private sector over the public and consumerism more generally. Despite this, RoboCop is often taken at face value as a Hard-Body film, indeed the protagonist is seen as the ultimate Hard-Body, his armour constructed from “titanium laminated with Kevlar”, therefore being an extension of the gym, and steroid, built bodies of Stallone and Schwarzenegger (indeed the panels of RoboCop’s armour mirror the shapes of such bodies). However, while RoboCop might appear as the ultimate hard-body the film asks questions of what lies inside the body and highlights it’s clearly constructed nature.

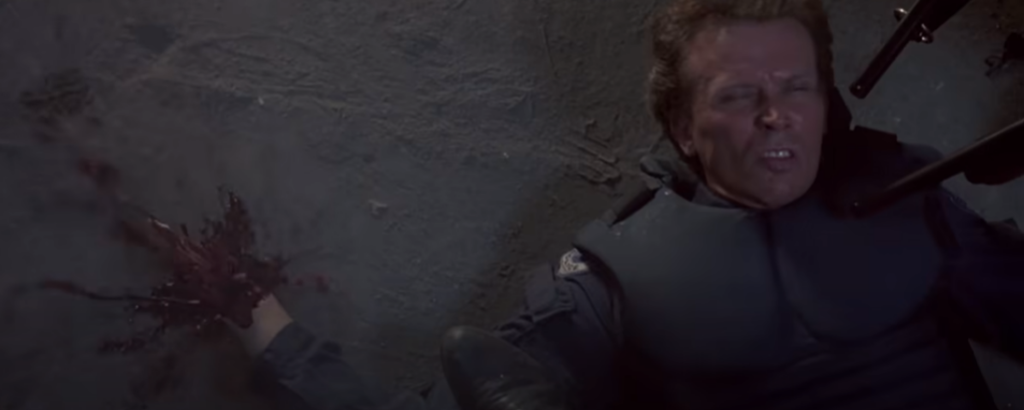

Much of RoboCop does conform to hard-body action tropes – we are given a hero who goes through a moment of ritualized suffering, only to return and defeat the various villains, therefore asserting his superior masculinity. However, Verhoeven pushes these conventions, taking them much further than the typical hard-body film. Compare a sequence in Rambo III where Rambo cleans and then cauterises a wound in his side, roughly two minutes of screen time, to Murphy’s prolonged, and detailed, dismemberment at the hands of Clarence Boddicker and his gang.

This situates Murphy’s body, more average looking than Rambo’s, as a soft body that needs to be rebuilt but the suffering of Murphy extends, perhaps throughout the whole movie. The steel works finale breaks Murphy’s now Robocop body down again, puncturing, piercing and crushing the outside – far beyond the injury of the typical hard-body hero. This is paralleled with other bodies throughout the film which are similarly broken down, revealing the soft mush inside, whether Boddiker’s spraying arterial blood or Emil’s whole body transformed into softness by toxic waste. The titanium armour succeeds in stopping bullets, but nothing can completely disavow the inevitable softness of the interior.

It is worth noting that RoboCop from the neck down is entirely a constructed product, we know this from the scene in which OCP Executive Bob Morton demands ‘total body prosthesis’ – that all remaining body material is disposed of. This asks questions then of the type of masculinity being presented, and what the spectator is being invited to identify with. In short RoboCop is a castrated corporate product.

His castration mirrors the absence of love interests in many of the Hard-Body films, but makes it literal. The essential element of masculinity, the phallus (in both the literal and symbolic sense) is absent. There are of course substitutes, the large gun RoboCop keeps in his leg for instance, or the ‘interface needle’ with which he kills crime lord Clarence Boddicker act as symbolic substitutes and confer RoboCop much of his power, but for RoboCop, unlike other Hard-Body heroes, the guns and armoured muscularity do not act as substitutes for the un-showable phallus – there is no organ to sublimate with symbolism here. Further to this loss, RoboCop, or Murphy, has lost the a key component of Reaganite policy, and traditional end-point of oedipal driven narratives, the family. Is it any wonder that, when confronted with images of his family, culminating in a curtailed sexual memory of his wife, RoboCop punches out a screen in frustration. Intriguing to that in one of the first crimes he prevents, the attempted rape of a woman by two assailants, RoboCop shoots one of them in the crotch. The hero’s castration is contrasted with the villains, who express an excessive lust (not just for women, but also drugs and violence). Verhoeven has spoken about his desire, early in the pre-production process, for Murphy and Lewis to have an affair, but later realising that ‘following American puritan standards’[vii] this wouldn’t work. This then, makes RoboCop an interesting comment on the Hard-Body hero – a body constructed (perhaps paralleling steroid use), lacking in genitals but having access to destructive phallic substitutes that connote power and strength.

This satire on the hard-body outside is paralleled by the questions of RoboCop’s identity and the question of Murphy’s ghost in the machine. During RoboCop’s recovery, having been attacked by the SWAT team, a distinctly Lacanian scene plays out. Removing his helmet for the first time, RoboCop sees Murphy’s face staring back at him – a moment that invokes the ‘mirror stage’, when the a young child comes to a moment of self-identification (which Christian Metz suggests is imitated by the cinema experience[viii]).

He then proceeds to destroy the baby-food Lewis has supplied for him, a symbolic act of growing up perhaps. The helmet remains off for the rest of the film, and when asked by OCP’s head, the patriarchally identified Old Man, for his name, he now replies ‘Murphy’. This seemingly confirms a moment of self-realization and self-identification, severing ties with the corporate product and reassertion of human individuality. But this triumphant moment is undercut in several ways – Murphy still requires the permission of the Old Man to kill Dick Jones (with the suggestive line ‘Dick, you’re fired’), his prime directives, including the classified ‘Any attempt to arrest a senior officer of OCP results in shutdown’ remains and the final cut of the film, hard-cutting from a smiling Murphy to the title card ‘RoboCop’ reasserts his nature as corporate product, suggesting that his reasserted identity is an illusion.

There is also the question of the bullet lodged in Murphy’s head, embedded in the prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain that ‘regulates thoughts, actions and emotions’[ix], and the area targeted by lobotomies. A sexless, lobotomized, corporate product – is this, perhaps, Verhoeven’s (and screenwriters Ed Neumeier and Michael Miner’s) view of the mythic heroism embodied by Stallone and Schwarzenegger? RoboCop, and through identification the spectator, have only the illusion of mastery here.

PART 2: IT’S THE LATEST THING IN TRAVEL. WE CALL IT THE EGO TRIP

The question of lobotomy is essential to Total Recall, it’s threat repeated several times to the hero Douglas Quaid. The casting of the ultimate hard-body, Arnold Schwarzenegger, as Quiad allowed Verhoeven to create a more hyperbolic film than perhaps first envisioned in the multiple script drafts. Rather than simply reiterate Schwarzenegger’s previous screen image however, Verhoeven uses the opportunity to subvert some of core elements of his star’s screen persona. Central to this are Quaid’s fantasies of Mars and desire to visit Rekall – in a sense even Arnie dreams of being Arnie and wants to take ‘a holiday from himself’. This tacitly points to the unreality of the Schwarzenegger image, that it is artificial in itself. Indeed, artificiality is a major concern of the film, whether it is in the sense of artificial memories, the predominance of screens (such as one in Quaid’s kitchen showing an artificial landscape), the Johnny Cab driver or the moment when Quaid becomes indistinguishable from his own holographic projection ‘Ha ha ha, you think this is the real Quaid…?’.

Perhaps the most subversive elements of the film is Verhoeven’s treatment of Schwarzenegger’s body which, other then an early scene, remains mostly covered by clothing. Gone are the explicit and fetishizing displays of muscularity. Instead, we have an elastic Arnold, one that cab be pulled and stretched in strange and unnatural ways. Three scenes show us this. The first is when Arnold removes the bug from his head, stretching his nose impossibly (and suggesting there was an unreasonably large gap somewhere in his head for it to be hidden), the moment when the ‘Two Weeks’ disguise pulls apart showing his head in an impossibly small space, and the finale where his eyes bulge and tongue lolls during his expulsion onto the airless Martian landscape (Quaid and Melina are marked out from Cohaagen by their ability to endure this stretching, in effect to be soft and malleable as opposed to hard and unyielding).

Of course, all these moments are performed by, very convincing, special effects, and these impossible moments return us to the questions concerning the real and fantasy that dominate the film (they also draw attention, in similar ways to how The Terminator does, to the fact there is something unreal about Schwarzenegger himself).

If the hard-body hero is made to have an elastic body here, the question of the mush inside returns in several ways. Visually it is dramatized through the mutants who populate Venusville on Mars – oxygen starvation has transformed their bodies, so that, in many cases, the barriers between internal and external have collapsed, organs breaking through their skin.

Returning to questions of fantasy and reality, we see how Verhoeven draws attention to the film’s narrative construction in the scenes where Quaid visits Rekall and the plot of the rest of the film is laid out exactly as his fantasy of being a secret agent who will ‘get the girl, kill the bad guys and save the entire planet.’ Quaid’s surrender to the fantasy mirrors the spectator’s, but it also throws doubts on our mastery of the narrative. By making the spectator conscious of the construction, then questioning its validity in the scene with Dr. Edgemar, our identification with Quaid, the spectator’s ‘Ego Trip’, is questioned and thrown into doubt. Despite this, Verhoeven allows the spectator to retain their feeling of mastery, as Quaid eventually wins, only to pull it away at the end. As Verhoeven describes regards Doug’s fate, ‘I mean he is lobotomized at the end. That’s why at the last shot, when they are so happy and kissing each other, it slowly fades to white, which to me meant “OK, there he goes. That’s the end-that’s the dream – they lobotomized him”’[x].

The archetypal hard-body hero, reconfigured as an elastic body – but elastic only through fantasy. Meanwhile he lies on a table somewhere, his brain turned to mush.

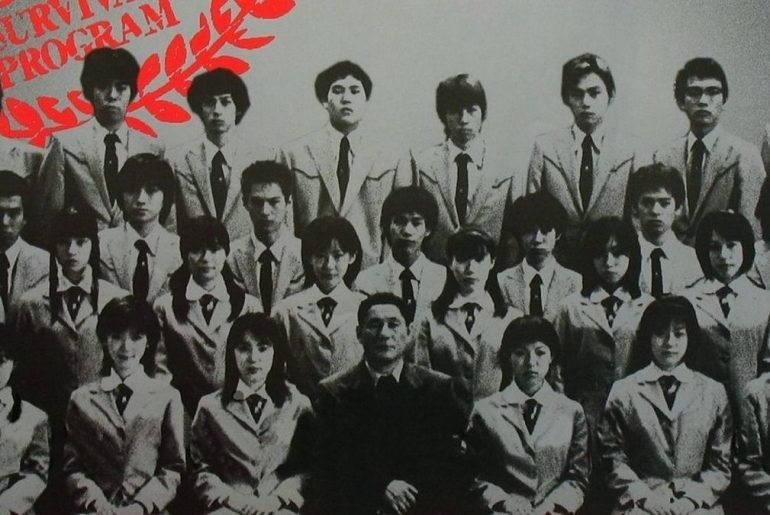

Part 3: They Sucked his Brains Out

Starship Troopers’ Johnny Rico is Verhoeven’s final critique of the hard-body hero – the individualist, muscled, American reduced to a simpleton unable to make decisions. As Verhoeven described it, the characters of Starship Troopers are ‘streamlined in a certain way… you could also call it lobotomised’.[xi] In the fascist future the film depicts even South Americans are reduced to being the corporate ideal of the bland US soap opera star; Rico, on the surface at least, appears to fulfil Jefford’s formula. He undergoes extreme suffering (the flogging which, like Murphy’s death in RoboCop, resembles the Crucifixion),

he possesses the muscular body that suggests mythic heroism, and moves through a series of action scenes. However, Rico never suggests any of the individuality Jeffords suggests, or that was part of the Reaganite messaging. Rather he is a character devoid of individual drive, manipulated by others, and incapable of making decisions.

Rico’s actions during the film are responses to others, rather than from a drive of his own. He decides to enlist (partly due to his teacher Rasczak, partly peer pressure) then changes his mind after his parents promise him a holiday, then changes his mind again (Carmen being a big influence), only to decide to leave the Mobile Infantry when Carmen dumps him, via a videoed Dear John letter. Despite gaining swift promotion in the field, there is little to suggest Rico has great leadership skills – rather he simply has a great capacity for surviving. He orders another trainee to remove their helmet during a live-fire exercise, which leads to the trainee’s death, and later he is guided to find the surviving Carmen, unknowingly, by his psychic friend Carl suggesting he has the mental ability similar to Carl’s pet ferret (who was similarly manipulated in an earlier scene). It is perhaps no wonder that a Brain Bug never threatens Rico – it is unlikely it would find much to suck out. But of course, the sucking out of brains by the Bug mirrors the sucking out of brains by the fascist society. As Rico gets promoted we watch as he simply adopts the persona of his teacher/commander Rasczak, imitating his dialogue and behaviours. Here the hard-body ideal is rendered brainless, lobotomized by society rather than a bullet or a Leucotome – Verhoeven himself stated ‘I felt that the soldier characters were all idiots. They were all willing to die… because of the propaganda they had been fed.’[xii]

And the film offers us a parallel hard-body, that of the bugs – in many ways harder-bodied than the humans and their armour which appears to offer little to no protection from attack. Indeed, the film is consistently reminding us of the fragility of the human body, from the various characters showing amputations and prosthetics, to the many violent ways in which the bugs kills the humans (including various bisections and decapitations). Rico himself is believed dead for a time after his leg is pierced through by an Arachnid. The bugs however are still fragile, and the film shows us the many ways in which they can also be reduced to the mush inside the hard carapace. One early scene, set at high school, shows the various organs of one bug and Rico’s takedown of the Tanker Bug throws orange goo up into his face. The only soft Bug, provocatively, is the Brain Bug – a soft mass that ripples and undulates. Is it significant too that the highly intelligent, and psychic, Carl is one of the few characters not to be defined by muscularity and physical action?

The mushy fragility of human life is always present – no amount of hardening (in literal muscularity or metaphorical political philosophies) can hide that fact. What then of mastery, as Rico shows such little of this quality (in some ways the real hero of the film is Drill Sargeant Zim who captures the Brain Bug). Whereas the two previous films were subtler in subverting the hard-body ideal, Starship Troopers is more direct by suggesting the very ideal is empty, individuality a myth in this ultra-right wing society.

Part 4: Consider this a Divorce.

Robin Wood, in discussing the Horror film from the 1960s to 1970s, suggests the following:

Two elementary Freudian Theses: in a civilization founded on monogamy and the family, there will be an immense, hence very dangerous, surplus of sexual energy that will have to be repressed; what is repressed must always struggle to return, in however disguised and distorted form.[xiii]

For Wood the horror film brings forth, through analogy, that which is repressed. During the Reagan administration there was an emphasis on the return to traditional family values[xiv], with several action films of the era (such as the Lethal Weapon films and Die Hard) reflecting this concern. More generally the hard-body film is one that largely represses sex, with very few sexual relationships for the heroes. Verhoeven’s three films have great fun in unpicking this, by bringing forth the sort of psychosexual imagery usually sublimated or disavowed in such films – except, perhaps, when displaced into muscles and weaponry. Castration imagery recurs, not only in Robocop where it is quite literal, as we’ve discussed, but in Total Recall through Lori’s crotch based attempts to subdue Quaid, to the amputation of Richter’s arms. Various limb removals in Starship Troopers reflect this too. Other, more explicit and challenging, psychosexual images are also in play: the quasi-male-birth of Quato out of George’s body, the killing of Benny via drill and the typical Arnie quip ‘Screw You’; the Martian pyramid reactor can be seen as a feminine space of caverns, that gives out a life saving ejaculation of air at the film’s climax; the Phallic Spaceships of the Federation are assaulted by semen like spays of plasma; Rico’s vaginal leg wound is healed in an amniotic tank; more caverns appear in Starship Troopers and the Brain Bug itself, is a nightmare blend of vaginal orifice and penetrating, sucking, appendage (which we only see attack men).

Marriage, one of the core elements of the Reaganite revival, tied to his support from the Evangelical Christian Right, is subverted too – a ‘lost paradise’ for Murphy to which he cannot return, a burden for Quaid that limits him from indulging in his fantasy (and easily dispatched with the one-liner, ‘Consider this a divorce’), and it is not even on the cards in Starship Troopers, where Carmen happily moves between men as her career progresses, men and women shower together without a hint of sex and Rico fails to retain a romantic partner.

This use of psychosexual imagery and subversion of marriage is, I would suggest, part of Verhoeven’s critique of what he sees as the ‘puritan attitude in America’ – bringing forth the desires and ideas that such as an attitude must repress.

Conclusion

In conclusion, these three films take the hard-body concept and subvert and play with it – the body is deconstructed, wounded and lobotomized. The individuality the hard-body was supposed to connote is withdrawn, and with it a complete sense of mastery for the spectator, either personal or collective.

In RoboCop Verhoeven shows the hard-body as a corporate construct, the hero’s return to individuality undermined by his persistent programming. In Total Recall the ultimate hard-body star, Arnold Schwarzenegger, is made elastic before a final lobotomy curtails the fantasy of being Arnold Schwarzenegger. And in Starship Troopers, perhaps the most thorough critique, the hard-body hero is the idiot soldier of a fascist republic, incapable of individual thought. Hard bodied perhaps, but mushy brained.

Bibliography

Arnsten A.F. (2009) Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nat Rev Neurosci. Jun;10(6):410-22. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2907136/#:~:text=The%20prefrontal%20cortex%20(PFC)%E2%80%94,detrimental%20effects%20of%20stress%20exposure. [accessed 03 September 2023].

Ayres, Drew (2008). Bodies, Bullets, and Bad Guys: Elements of the Hard Body Film. Film Criticism. 32 (3), 41-67.

Cornea, Christine (2007). Science Fiction Cinema: Between Fantasy and Reality. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Ellis, John (1994). Visible Fictions: Cinema, Television, Video. London: Routledge.

Glass, Fred (1990). Totally Recalling Arnold: Sex and Violence in the New Bad Future. Film Quarterly, 44 (1), pp. 2-13.

Jeffords, Susan (1993). Can Masculinity be Terminated?, in Cohan, S. & Hark, I.R. (eds.). Screening the Male: Exploring Masculinities in Hollywood Cinema. London: Routledge, pp. 245-262.

Jeffords, Susan (1994). Hard Bodies: Hollywood Masculinity in the Reagan Era. Rutgers University Press: New Jersey.

Kac-Vergne, Marianne (2018). Masculinity in Contemporary Science Fiction Cinema: Cyborgs, Troopers and other Men of the Future. London: I.B. Taurus.

Keesey, Douglas (2005). Paul Verhoeven. Cologne: Taschen.

LaBruce, Bruce (2003). Paul Verhoeven. In (ed) Barton-Fumo, M. (2016) Paul Verhoeven: Interviews. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Lebeau, Vicky (2019). Psychoanalysis and Cinema: The Play of Shadows. Columbia University Press: New York

O’Brien, Harvey (2012). Action Movies: The Cinema of Striking Back. Wallflower Press: New York.

Ryan, Michael & Kellner, Douglas (1990). Camera Politica: The Politics and Ideology of Contemporary Hollywood Film. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Shea, C. & Jennings, W. (1992) Paul Verhoeven: An Interview. In (ed) Barton-Fumo, M. (2016) Paul Verhoeven: Interviews. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Tasker, Yvonne (1993). Spectacular Bodies: Gender, Genre and the Action Cinema. London: Routledge.

Telotte, J.P. (2001). Verhoeven, and the Problem of the Real: “Starship Troopers”. Literature/Film Quarterly. 29 (3), pp. 196-202.

van Scheers, Rob (1998). Paul Verhoeven. London: Faber & Faber.

[i] Jeffords (1994) 8-9.

[ii] Jeffords (1994) 11.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Jeffords (1994) 16.

[v] Ibid 28.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Cornea (2007) 136.

[viii] Fuery (2000) 15.

[ix] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2907136/#:~:text=The%20prefrontal%20cortex%20(PFC)%E2%80%94,detrimental%20effects%20of%20stress%20exposure.

[x] Shea & Jennings (1992), in Barton-Fumo (ed) (2016), 75.

[xi] Cornea (2007) 172.

[xii] LaBruce (2003) 154.

[xiii] Wood (2018) 57.

[xiv] Jeffords (1994) 191.

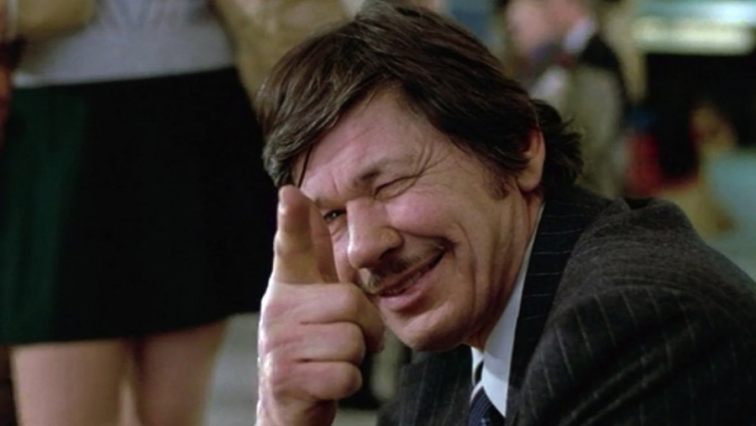

A prologue, filmed at the studio’s behest after they became nervous of Russell’s performance, only serves to build up his character, making the reality even funnier. Chinese mystic Egg Shen (Victor Wong) tells a lawyer that the world “owes a debt of gratitude to Jack Burton”, before we cut straight to Burton’s truck in which he, between mouthfuls of sandwich, speaks ridiculous platitudes to his CB radio:

A prologue, filmed at the studio’s behest after they became nervous of Russell’s performance, only serves to build up his character, making the reality even funnier. Chinese mystic Egg Shen (Victor Wong) tells a lawyer that the world “owes a debt of gratitude to Jack Burton”, before we cut straight to Burton’s truck in which he, between mouthfuls of sandwich, speaks ridiculous platitudes to his CB radio: is a bull-shitting protagonist with no idea what’s going on, blundering into an Asian culture and presuming that everyone there will simply bow down to him and his bluster (shades of Vietnam?). Wang is his friend and allows Burton to tag along in attempts to rescue Wang’s betrothed Miao Yin (Suzee Pai) but it’s extraordinary how useless Burton is, and how little he realises it. Indeed, it’s his posturing at the airport that creates the sequence of events that lead to Miao Yin’s kidnapping – if he hadn’t gone with Wang perhaps none of this would have occurred…

is a bull-shitting protagonist with no idea what’s going on, blundering into an Asian culture and presuming that everyone there will simply bow down to him and his bluster (shades of Vietnam?). Wang is his friend and allows Burton to tag along in attempts to rescue Wang’s betrothed Miao Yin (Suzee Pai) but it’s extraordinary how useless Burton is, and how little he realises it. Indeed, it’s his posturing at the airport that creates the sequence of events that lead to Miao Yin’s kidnapping – if he hadn’t gone with Wang perhaps none of this would have occurred…

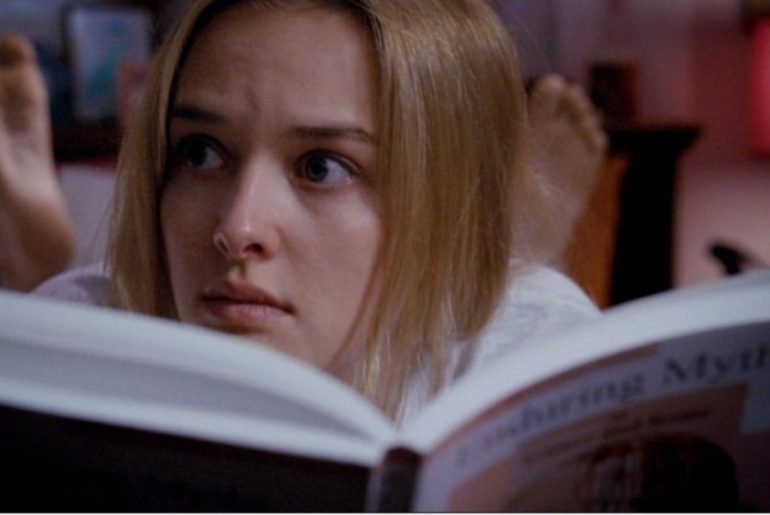

On the surface Society plays on recurrent adolescent fears of entering adulthood, especially in the realms of sexual relations. In many horror films, especially in the Slasher sub-genre, anxieties faced by the adolescent are dramatized; the killer, or monster, which must be conquered stands in for the desires/fears that need to be repressed for successful entry into the symbolic order. That the monster has a sexual ambiguity to it has been noted and extensively examined (particularly by Carol Clover). In many respects Society follows this formula as it centres on Billy Whitney (Billy Warlock

On the surface Society plays on recurrent adolescent fears of entering adulthood, especially in the realms of sexual relations. In many horror films, especially in the Slasher sub-genre, anxieties faced by the adolescent are dramatized; the killer, or monster, which must be conquered stands in for the desires/fears that need to be repressed for successful entry into the symbolic order. That the monster has a sexual ambiguity to it has been noted and extensively examined (particularly by Carol Clover). In many respects Society follows this formula as it centres on Billy Whitney (Billy Warlock The opening of the film foregrounds this willingness to be subversive and to blur boundaries between reality and fantasy. A typical dream sequence occurs in which Billy, clutching the classic slasher weapon of the kitchen knife, walks scared through his own house, only to be confronted by his mother all the while a female voice sings a haunting rendition of the Eton Boating Song (reminiscent of the use of nursery rhymes in the Elm Street series and tying the film to old-world class structures). The film cuts to the psychiatrist’s office where Billy confides his feelings of fear and dread to Dr Cleveland. Billy takes an apple and bites, revealing worms within. It’s an obvious but still potent symbol of the corruption under the skin in this supposed Eden. Then, adding another surreal layer, it cuts to a flash-forward of the Shunting, allowing us to see merged body parts, covered in a sticky fluid with muted moans as the Eton Boating Song Resumes with a new re-written lyric;

The opening of the film foregrounds this willingness to be subversive and to blur boundaries between reality and fantasy. A typical dream sequence occurs in which Billy, clutching the classic slasher weapon of the kitchen knife, walks scared through his own house, only to be confronted by his mother all the while a female voice sings a haunting rendition of the Eton Boating Song (reminiscent of the use of nursery rhymes in the Elm Street series and tying the film to old-world class structures). The film cuts to the psychiatrist’s office where Billy confides his feelings of fear and dread to Dr Cleveland. Billy takes an apple and bites, revealing worms within. It’s an obvious but still potent symbol of the corruption under the skin in this supposed Eden. Then, adding another surreal layer, it cuts to a flash-forward of the Shunting, allowing us to see merged body parts, covered in a sticky fluid with muted moans as the Eton Boating Song Resumes with a new re-written lyric;