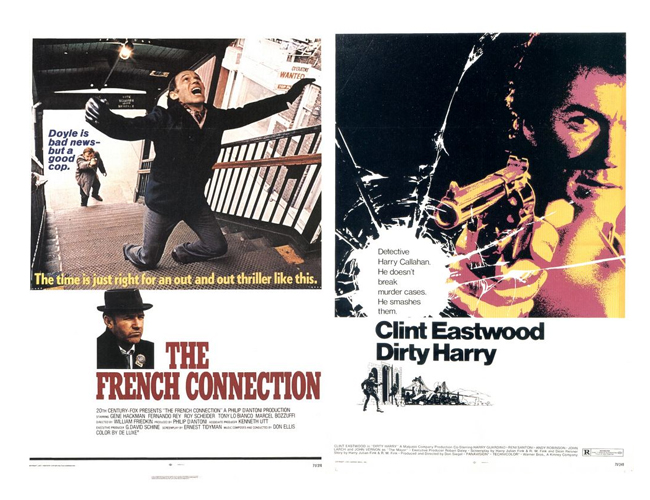

One of them is a loner who gets thrown every dirty job in town. His solution: shoot his .44 Magnum and damn the consequences. The other is a blue-collar roughneck, a porkpie-hat wearing boot fetishist as likely to shoot a colleague as he is a bad-guy. Welcome to 1971. Welcome to the birth of the modern action hero. It wasn’t a smooth delivery. The critics reacted with catcalls of “fascist”. Roger Ebert wrote, “if anybody is writing a book on the rise of fascism in America, they ought to take a look at Dirty Harry”. Garrett Epps of The New York Times asked “Does Popeye Doyle Teach us to be Fascist?”, deciding no, but that The French Connection is a “celebration of authority, brutality and racism” (which sounds pretty fascist to me). Dirty Harry on the other hand “is a simply told story of the Nietzschean superman and his sado-masochistic pleasures”. Pauline Kael, never a fan of Eastwood, described Dirty Harry as a “right wing fantasy” and The French Connection as featuring “the latest model sadistic cop”. Vincent Canby, also in The New York Times, decried Dirty Harry with the criticism, “I doubt even the genius of Leni Riefenstahl could make it artistically acceptable”. Something about these films got up the nose of American critics. Perhaps this was only made worse by their popularity with audiences. But how did early 70s cinema come to embrace these men, and the McClanes, Riggs and Cobrettis to follow?

Looking back over the history of cinema two types of film dominated action before 1971; the western and the war film. It all changed, in the 1960s as the cops began to take over. They brought the action into the city, finding a new wilderness among the streets and the neon lights. Cities became the new frontier, dark, shadowy and fuelled by drugs. It reflected the changes in American society; the huge rises in crime, particularly mugging, had Americans scared to walk city streets. This was a different America and it needed different heroes. The French Connection and Dirty Harry redefined how America’s heroes would look and act, casting a shadow over action cinema for a generation to come. The story goes that 1960s cinema ended in counter-culture revolution. Led by Bonnie and Clyde (Arthur Penn, 1967), The Graduate (Mike Nichols, 1967) and Easy Rider (Dennis Hopper, 1968) the audience found themselves on the side of the law-breakers, railing against society, whether it be the cops, the banks or the politicians. Take a closer look and another, parallel, story comes clear. The success of films like The Dirty Dozen (Robert Aldrich, 1967) and Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy, alongside the earlier, harsher Bond films, showed that there was an audience for tough heroes. What was different about them was how they abandoned the codes of the past – these guys were selfish, in it for themselves, often only doing the right thing incidentally. These weren’t the classic heroes of the past, the sort that Joseph Campbell wrote about. They were anti-heroes, the dark shadows of heroism. Ever since WW2 heroes had been getting darker, as if the horror of human behaviour exposed in Europe and the Far East had leached out the possibility of anybody being truly good. Even John Wayne got in on the act in The Searchers (John Ford, 1956). It’s difficult to imagine now because, by and large, today all movie heroes are anti-heroes. Go back to the 1940s and watch Errol Flynn or James Stewart and see men who do right because it’s right to do it. As American life got more complicated, with conflict at home and abroad, it became harder and harder to find purity in anyone’s motives. It would get worse before the 60s was out.

Charles Whitman climbed a tower at the University of Texas in Huston in August 1966 and started shooting. He killed 14 and wounded 31 before the Police shot him. The shadow of the Zodiac killer settled over San Francisco in the late 1960s as he taunted Police with his letters. He was never found. And in 1969 Charles Manson’s ‘family’ broke into 10050 Cielo Drive murdering, among four others, Sharon Tate, pregnant actress and girlfriend of Roman Polanski: all three helped signal a change. Nobody was safe anymore, not even Hollywood stars. It was the final nail in the coffin of 60s optimism. All the leaders, Kennedy and King, were dead. The movie heroes of old didn’t cut it (just watch Wayne’s self-directed Green Berets (1968) or Brannigan (Douglas Hickcox, 1975) for evidence). America needed new symbols to help it feel safe at night. Cue Jimmy ‘Popeye’ Doyle and ‘Dirty’ Harry Callahan, although in many ways The French Connection and Dirty Harry couldn’t be more different. The former was directed by a precocious young director from TV noted for several art-house style films, the latter made by one of Hollywood’s old hands, who could trace his career back to Hollywood at its peak in the 1930s and 40s. But what both William Friedkin and Don Siegel understood was that the time was ripe for a new, tougher, more cynical hero.

Friedkin had been circulating for several years in Hollywood and had been tipped as a hot director. He mastered his craft making documentaries on the streets of his home town Chicago, working areas other film-makers wouldn’t touch like the black South-Side. He was an abrasive young man, supremely talented, directing for TV in his early twenties. Siegel began at Warner’s back when the Studio System was in its heyday. He began in the Film Library Department, moving through the company to Editorial and Insert departments. Here he contributed to some classics like The Roaring Twenties (Raoul Walsh, 1939) and Confessions of a Nazi Spy (Anatole Litvak, 1939). He worked with such greats as Michael Curtiz (director of The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) and Casablanca (1942)) and Howard Hughes, eventually graduating to directing at Hughes’ RKO. The movie he will always be remembered for, other than Dirty Harry, is Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1962), regularly cited as the best B-movie ever made. An efficient director, Siegel worked quickly and effectively. He shot what he needed, scouted his own locations and liked to collaborate. He was just the sort of director Clint Eastwood appreciated. By 1970 Friedkin’s career was stalling. He was making movies, dramas such as The Boys in the Band (1970), but his films weren’t making any money. That would all change after an encounter with Howard Hawks. “People don’t want stories about somebody’s problems or any of that psychological shit”, Hawks told him, “What they want is action stories. Every time I made a film like that, with a lotta good guys against bad guys, it had a lotta success, if that matters to you”. It mattered to him alright. His next film was The French Connection.

Siegel and Eastwood first met on Coogan’s Bluff (1968), an early attempt to translate Eastwood’s Spaghetti Western success to America. It worked, with Eastwood starring as an Arizona lawman relocated to New York to extradite a suspect. It featured some brutal action, including a great bar fight. Coogan’s single minded pursuit of hippy suspect Ringerman, and willingness to ignore regulations, served as a prototype for Harry. With Dirty Harry they were able to create a purer distillation of the action formula from Coogan, dumping the unnecessary love interest, turning the conflict between Harry and Scorpio into the focus. Watch Harry again and it might even seem that the sado-masochistic relationship between cop and killer is its own sort of twisted romance, camera flying away from the stadium to protect their privacy when they are finally alone. The producer of The French Connection, Philip D’Antioni, previously brought Bullitt (Peter Yates) to the screen in 1968. Inspired by real events, and the book by Robin Moore, The French Connection provided a chance to repeat the earlier success. For that purpose he demanded one thing from Friedkin, a car chase to beat the one in Bullitt. Both the chase and its filming are now legendary but are just one part of a film which constantly innovates and defies convention. Filming in a down and dirty documentary style, casting a character actor, Gene Hackman, in the lead, allowing cast to improvise (a cast which included real life “Popeye” Eddie Egan as Doyle’s boss), and taking cues from The French New Wave, The French Connection is like nothing else produced in Hollywood at the time. It’s also groundbreakingly violent. Just witness the car-crash victims; they’re nothing to do with the plot but Friedkin lets his camera linger over the mess of their bodies. Then think about that final shot. What other Hollywood film leaves the audience with such a bleak and unresolved ending, Doyle charging off into the darkness having shot one of his own colleagues?

You can see how real life events influenced Dirty Harry. Check out Scorpio and you can see the influence of Manson, the Zodiac killer and Whitman; Scorpio represented everything that was going wrong with America, and he could even have been a returning Vietnam veteran with his military boots and rifle proficiency. Those who read Callahan as an authoritarian figure taking on a hippy loner miss the point, though. Yes Scorpio is all that’s bad but Harry’s not much better. As the film plays out, a teasing parallel between Scorpio and Harry emerges, they’re both voyeurs, both loners, both killers. Their combat is a dance to the death across the streets of San Francisco. That late 60s anti-authoritarian streak runs through Callahan and Doyle and shows that these films have more in common with the Easy Riders of this world that you might think. Both are fierce individuals, outsiders who don’t fit in to society – but the difference is they’re there trying to make it work. Both films hinge on their heroes. They’re a strange pair, both loners paired with partners whose normalcy only highlights their extremes, both isolated by society. Friedkin pulls no punches in his depiction of Popeye as a slovenly, driven and violent man. Watch the scene where Frog One, Charnier, enjoys a three course meal while Popeye stands outside drinking stale coffee and eating greasy pizza. It’s a wonderful evocation of the thankless task that stands before the police; the street smart blue-collar worker living in a small apartment that resembles a prison cell versus the urbane French charmer with a house on the Riviera. Dirty Harry‘s opening shots, hovering over a memorial board to San Francisco police men points to the danger and thanklessness of the task. In some senses they’re the reincarnation of the Western hero dragged into the city, the lone gunman dealing with injustice. But in the city their actions provoke outraged responses, the cushion of myth having been removed. Just like Will Kane in High Noon (Fred Zinnemann, 1952), who like Harry throws his badge away, they’re abandoned by the townsfolk and have to do what’s best on their own.

Initial reaction to both films was fierce, many critics highlighting the violence, but Dirty Harry was by far the most kicked about. Harry’s perceived racism was a particular bone of contention, despite the fact that he has friends and enemies of different races. Both Siegel and Eastwood have been on record defending the films from such accusations. In his autobiography, A Siegel Film, the director described his approach, “If I do a film about a murderer, it doesn’t mean that I condone murder. If I do a film about a hard-nosed cop, of course it doesn’t mean I condone all his actions. I find it very difficult to explain my reasons for making a film like Dirty Harry, other than I’m a firm believer in entertainment, hoping that every picture make will be a commercial success. Not once throughout Dirty Harry did Clint and I have a political discussion.” Similarly The French Connection found its critics, suggesting the film to be racist and authoritarian, but it also registered far more supporters. It was a huge box-office success ($30million plus in the US alone) and won five Oscars, including best director. Dirty Harry won no awards, but took over $28 million and cemented Eastwood’s star status. The impact of these two films still resonates through their sequels and imitators. As Eastwood proved in Gran Torino (2008) he has never really escaped the shadow of Callahan. The lone cop, the disregard for superiors, for red tape and rules, the brutality of the violence; these can all be seen in modern action movies. Check out the rivalry between John McClane and his slick European rival, Hans Gruber, in Die Hard (John McTiernan, 1988); it clearly echoes Doyle and Charnier. What is Riggs but Callahan pushed to his logical, suicidal extreme? How about that scene in Lethal Weapon (Richard Donner, 1987) with the jumper? Straight out of Dirty Harry. Come to think of it aren’t both Die Hard with a Vengeance (John McTiernan, 1995) and 12 Rounds (Renny Harlin, 2009) just two hour remakes of the phone chase in Dirty Harry? Look at any cop-thriller or action film from the 1980s or 90s and the influence of Doyle and Callahan is clear. Fascist Super Cops? No. Fascists aren’t free thinkers, they don’t possess the cynical edge of these men, the individuality. The critics saw the violence, but missed the point. The audience got it. And we’re still getting it today.