In 1967 Stanley Fish published a seminal work that reconceptualised the understanding of John Milton’s Paradise Lost. In Seduced by Sin Fish argued that the true subject of Paradise Lost was not Satan, or Adam and Eve, but the reader himself who, through the epic poem’s structure and use of recognisable narrative forms (Satan’s heroic journey being patterned on The Odyssey and The Aeneid), experiences his own fall. For Fish the reader is “confronted with evidence of his corruption” (1967, ixxii) when he realises his seduction by Satan’s heroic narrative and should, by the end of the work, come to realise his own temptations and spiritual limitations, becoming a sort of guilty reader who develops an understanding of the limits of his own spirituality.

At first glance a 17th Century English poetic work seems to have little in common with Death Wish, a film that has long been neglected by serious critics despite its box-office success and evident influence on cinema (arguably starting a whole sub-genre of vigilante/revenge films which continues to this day, with a 2018 re-make). Indeed Death Wish was received with outright hostility by most main-stream critics in the US and UK, and still exists as a sort of by-word for violent exploitative film – happily referenced during real-life crimes, such as those of Bernie Goetz in 1984, by lazy journalists.

On its release Vincent Canby, in The New York Times, called it

a despicable movie, one that raises complex questions in order to offer bigoted, frivolous, oversimplified answers

in July 1974, returning in August to decry its popularity with “law-and-order fanatics, sadists, muggers, club women, fathers, older sisters, masochists, policemen, politicians, and, it seems, a number of film critics”. Roger Ebert denounced it as “propaganda for private gun ownership and a call to vigilante justice”, and Richard Schickel called it “vicious”. Judy Klemersud was sent by The New York Times to answer the question “What do They See in ‘Death Wish’?”, noticing how audiences cheered when Bronson (as the audience identified him, not his character Paul Kersey) gunned down muggers, and confessing that she too found herself, much to her shame, “applauding several times.” A clear characterisation of the film and its audience emerged, but if it was intended to warn away movie-goers it failed as the film took over £20 million in the US on a budget of $3million (Talbot 2006, 8).

But what if there’s something more complex at work in Death Wish? What if we can take Fish’s ideas about the reader in Paradise Lost and apply them to a film written off as exploitation? What emerges is a film much more complicated than previously assumed – one that tempts the spectator into identification with a psychotic protagonist, forcing them to reflect on their own sense of law, order and justice and the lure of simplistic answers to complicated problems.

Use of Myth & Genre

Many critics have perceived Death Wish as a sort of “urban Western”, an attempt to relocate the form to a more relevant setting, taking account of the demythologising of the genre that occurred through the 1960s and the early 1970s (through the Spaghetti Westerns and revisionist films such as Little Big Man (Arthur Penn, 1970)). There is much on the surface that makes this suggestion appealing; Death Wish repeatedly references the codes of law and order represented in the Western, most notably in Paul Kersey’s journey to Tucson where his is schooled in “the old American tradition of self-defence” by Aimes Jainchill, the sort of man who carries a gun openly and has bull horns on his car. The casting of Bronson as Kersey, who came to fame in The Magnificent Seven (John Sturges, 1960) and cemented his association with the genre in Once Upon a Time in the West (Sergio Leone, 1968), furthers this, lending the theory some pertinence which is helped by the film’s direction.

Winner directs the film in a traditional Hollywood style (despite his English nationality), eschewing the experiments of form that characterise the New Hollywood period when the film was produced. Indeed one could quite happily label his work as heavy handed, if efficient in covering ground quickly. Generally speaking, except in the infamous rape scene, Winner avoids using subjective techniques, instead allowing the spectator to remain distanced from the action, watching it unfold rather than being in the centre of it. This lends the film a sort of comfort in its spectating position, as does the use of genre tropes from the Western, helping to put the spectator at their ease.

When Kersey’s wife and daughter are attacked the attacker’s behaviour can easily be compared to that of the “Red Indians” in any of the multitude of Westerns audiences had familiarised themselves with through film and television during the past decades.

Much of the initial critical opprobrium directed at the film stemmed from the rape scene and Winner directs it to cause maximum offence and impact – the effect of this is two-fold. First it brings to life the implicit rape threat that was contained in many Westerns for a modern audience more accustomed to such images by films such as A Clockwork Orange (Stanley Kubrick, 1971) and Straw Dogs (Sam Peckinpah, 1971), but also it’s critical for the rest of the film that the crime be sufficiently disturbing that Kersey’s reaction to it seems, on the surface at least, reasonable. From this Kersey’s rediscovery of a Western code of justice follows, with the crime fitting that code – it is after all his “women-folk” who have been attacked in his urban “home-stead” (his wife is killed, the daughter is left in a vegetative state, conveniently unable to voice her own views).

Underpinning the Western genre is a binary opposition between the Wilderness and Civilization, the former a male environment in which the hero belonged, versus the feminizing force of the latter and Death Wish plays with this suggesting that the feminising power of civilization has left Kersey unable to protect his family, and the authorities impotent in the face of crime. Such a philosophy is espoused by Jainchill during the Tuscon segment, where the wide open spaces are contrasted to the dark alleys of New York. Here Kersey witnesses a Wild West show, an artificial and corny representation that beguiles him. Here he discovers a simple answer to New York’s crime problems – the good man versus the bad man.

Generating Complicity

There is no doubting the seriousness of crime, and especially mugging, during the 1970s so one can assume a certain pre-existing sympathy on behalf of the spectator, especially as they had paid to see a film in which the advertising campaign had highlighted the controversial elements (the tag-line read “Vigilante, city style – judge, jury and executioner”). But the film goes further in seducing the audience towards being sympathetic to Kersey by surrounding his actions with supporters and suggestions that his acts would have a significant impact on crime (the DA claiming a reduction in mugging from 950 per week to 470). The representation of the media within the film, complete with Western inspired imagery such as a noose and the headline “Frontier Justice in the Streets” on the cover of Harper’s, serves to cement this. A consistent narrative of Kersey’s effectiveness is built up – so much that it inspires other New Yorkers to defend themselves (such as Alma Lee Brown, seen in a TV news report, defending herself with a hat-pin).

These elements, alongside the comforting familiarity of the Western model, invite the spectator to align more closely with Kersey as the film continues, as does the comparison provided by Kersey’s ineffectual son-in-law and the scenes in which Kersey is confronted by a police force unable to catch his wife & daughter’s attackers. Having primed us in Tuscon the film returns to New York where Kersey starts acting out his new found sense of law and order, imaging himself to be the lawman of myth.

Kersey’s first act of violence is in self-defence (using a sock filled with a roll of coins), his second (this time with the revolver given to him by Jainchill) saves a man from being mugged. These actions fit within the narrative conventions of the Western, ideas of self-defence or helping the defenceless. They may be the acts of a vigilante, but they retain a certain sympathy, especially as Kersey reacts traumatically (vomiting after the first instance).

From then on Kersey’s actions become more sinister: he begins riding the Subway miles away from home waiting for someone to attack. He cruises the parks with no intent to look for people to save, rather he deliberately makes himself a target, enticing attackers by placing himself in vulnerable positions. And he begins to enjoy it. At home he surrounds himself with the newspapers and magazines that detail his exploits, watching the news reports that validate his actions with a broad smile on his face. He has moved well beyond the desire to protect himself and, of course, he has spent no time at all searching for those who harmed his family. It’s an often neglected detail, but a key one;

Death Wish is not a film about vengeance, at least not in a direct sense. Although the attack on his wife and daughter instigates a change in how Kersey views the world, none of his subsequent acts are directed towards punishing those responsible.

To have done so would have more easily placed Kersey into a pre-existing narrative schema, recognisable from films such as The Searchers (John Ford, 1956), but the film simply elides its way past this point and takes the spectator with it. We have the justification for Kersey’s crusade, but by omitting a direct vengeance against the criminals responsible the film moves slowly away from expectations towards something more complex and troubling. By the time Kersey is shooting men in the back, about as far from the Western code as you can get, the spectator is positioned so as not to notice the departure from expectations.

Revealing the Truth

On reflection cracks in this world appear early, indeed even in the opening prologue (added by Winner, and not present in the original novel by Brian Garfield) in which Kersey and his Wife enjoy a holiday. Ostensibly included to increase the tragedy that follows and to draw a direct comparison with the Hellish New York that follows, Hawaii is represented as an Edenic space, a land of plenty. However anyone with a cursory knowledge of crime on the islands can recognise this image as a sham, the resort an artifice behind which lies high levels of violent crime and drug-use. This effectively preys on our understandings of binary oppositions, the calm pastoral idyll as opposed to the degradations of civilization – however this Eden is so obviously false, as is the world of Tucson presented later which Kersey is so beguiled by. The Wild West show, from which Kersey draws inspiration, is over the top, a tired rehash of clichés for children and tourists in which the gun shots and deaths are clearly fake. Jainchill himself is an over the top caricature. Winner gently suggests to us here that the world that Kersey identifies with is a sham in itself; what values can possibly be drawn from it?

Alone in the film, as a voice of reason, is Detective Ochoa (Vincent Gardenia) edging towards the only logical conclusion about Paul Kersey: that he has become a serial killer. Ochoa provides an alternative protagonist in the film, but he is drawn to be uninspiring, a man of stubby cigars and crumpled coat, stuck with a permanent cold, as if crime was a literal disease. In a different edit of the film one could imagine Ochoa becoming the hero, tracking down Kersey the killer, but this would remove the growing moral complexity from the film, cemented when Ochoa tells Kersey to leave New York.

What of Kersey at this point? He has descended into a psychotic state, believing himself to be a lawman in the Old West; of course his targets aren’t the Native Americans of the films, or the bad men in black hats, but young urban men whose lives can only be hinted at.

During the final confrontation the young black man Kersey has chased and cornered can only be confused by the demand to “Draw” and “Fill your hand” – codes utterly inaccessible and irrelevant to someone who had previously exhorted Kersey to “Come on down, Mother Fucker”.

When confronted by Ochoa Kersey inquires if he has to leave town “by sundown?” Slowly, but inexorably, through the film, Kersey has bought into his own fantasies of law and order, coming to see himself as the hero of the West, but moving on to being someone who cannot distinguish between reality and fantasy.

Gotcha!

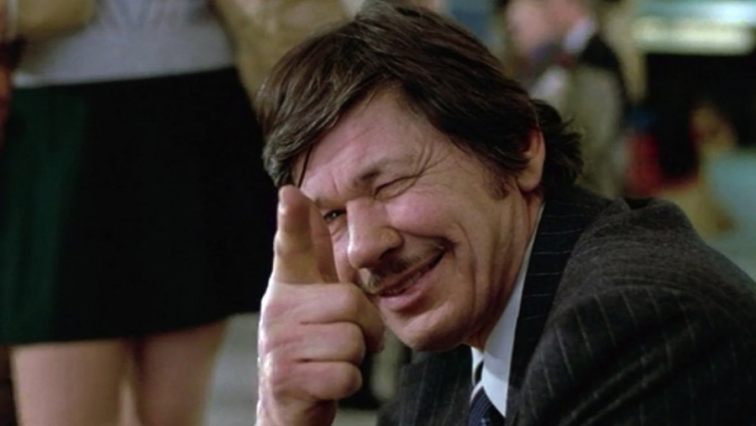

During the final moments of Death Wish Paul Kersey arrives in Chicago and, having disembarked from his train, is confronted by the sight of a gang of young men harassing a woman. As Kersey helps the woman recover the belongings that have been scattered over the floor he turns to the young men and forms his fingers into a gun shape, smiling broadly. But look at that shot again and you can see that the finger, ostensibly aimed at the young men, is pointing straight at us. It’s an image that reaches all the way back to 1903 and the first Western, Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery, which, as the legend goes, had the audience ducking under their seats with its final image of a bandit shooting straight towards the camera. The image has been remade, but the implication is the same – you’re next. The modern audience of course considers itself too sophisticated to duck their heads at such an image, but have they been too sophisticated to be seduced by Death Wish?

Through its use of familiar tropes and structures Death Wish plays out a tempting fantasy, one of easy answers to complicated questions. But rather than simply endorse Paul Kersey the film turns to the spectator and asks whether they too have been drawn in to this fantasy – a fantasy in which complex problems of urban degradation are made into narratives of good men versus bad men. The subtle hints that pepper the narrative, undermining its representations, point to a question for the spectator – are they too to be seduced like the Kersey’s many supporters in the city? As he turns to the camera in the final seconds Bronson reveals the film’s trick – a gothca moment designed to entrap us.

Just as Fish suggests regards Paradise Lost, the real subject of Death Wish is the audience. The question it asks them: are you conscious enough to see your own temptations?

Works Cited

Ebert, Roger (1974) Death Wish. Chicago Sun Times. [online] http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/death-wish-1974 [accessed 10 September 2017]

Fish, Stanley (1967) Seduced by Sin: The Reader in Paradise Lost. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Gilliat, Penelope (1974) Death Wish. New Yorker Magazine. 26 August.

Klemersrud, Judy (1974) What do They See in Death Wish? The New York Times. 01 September.

Schickel, Richard (1974) Mug Shooting. Time. 19 August.

Talbot, Paul (2006) Bronson’s Loose! The Making of the Death Wish Films. Lincoln: iUniverse

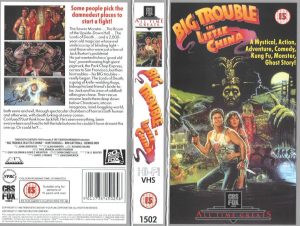

A prologue, filmed at the studio’s behest after they became nervous of Russell’s performance, only serves to build up his character, making the reality even funnier. Chinese mystic Egg Shen (Victor Wong) tells a lawyer that the world “owes a debt of gratitude to Jack Burton”, before we cut straight to Burton’s truck in which he, between mouthfuls of sandwich, speaks ridiculous platitudes to his CB radio:

A prologue, filmed at the studio’s behest after they became nervous of Russell’s performance, only serves to build up his character, making the reality even funnier. Chinese mystic Egg Shen (Victor Wong) tells a lawyer that the world “owes a debt of gratitude to Jack Burton”, before we cut straight to Burton’s truck in which he, between mouthfuls of sandwich, speaks ridiculous platitudes to his CB radio: is a bull-shitting protagonist with no idea what’s going on, blundering into an Asian culture and presuming that everyone there will simply bow down to him and his bluster (shades of Vietnam?). Wang is his friend and allows Burton to tag along in attempts to rescue Wang’s betrothed Miao Yin (Suzee Pai) but it’s extraordinary how useless Burton is, and how little he realises it. Indeed, it’s his posturing at the airport that creates the sequence of events that lead to Miao Yin’s kidnapping – if he hadn’t gone with Wang perhaps none of this would have occurred…

is a bull-shitting protagonist with no idea what’s going on, blundering into an Asian culture and presuming that everyone there will simply bow down to him and his bluster (shades of Vietnam?). Wang is his friend and allows Burton to tag along in attempts to rescue Wang’s betrothed Miao Yin (Suzee Pai) but it’s extraordinary how useless Burton is, and how little he realises it. Indeed, it’s his posturing at the airport that creates the sequence of events that lead to Miao Yin’s kidnapping – if he hadn’t gone with Wang perhaps none of this would have occurred…