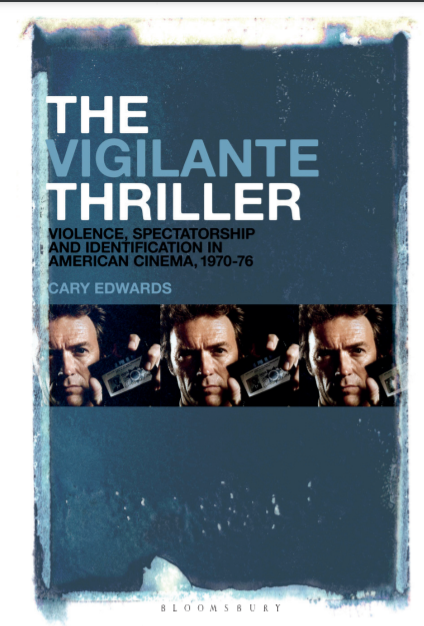

Well, blow me down. Here’s The Vigilante Thriller on a list of Best Thriller Film Books, in some pretty good company. Lord knows if it’s that good (all time…?!), but it’s nice to be included by Book Authority at number 14!.

Well, blow me down. Here’s The Vigilante Thriller on a list of Best Thriller Film Books, in some pretty good company. Lord knows if it’s that good (all time…?!), but it’s nice to be included by Book Authority at number 14!.

Great to say that The Vigilante Thriller is out in paperback in January – too late to fill a stocking perhaps, but just right for spending vouchers on. At time of writing it’s also reduced a little – click here for Bloomsbury’s official site (of course, it is available everywhere books are sold).

Bangor University – 7 & 8 September 2023

I had the great pleasure to return to Bangor University recently at participate in the Paul Verhoeven@85 Conference – a great set of panels discussing the works of a rather neglected director. Organised by Professor Nathan Abrams and Doctor Elizabeth Miller the conference covered all of Verhoeven’s three distinct periods, the early Dutch films, his move to the US, and his return to European filmmaking, and took a wide range of approaches, including looking at philosophy, politics, ideology and some interdisciplinary talks that covered Special Effects, Amputation and the ethics of public and private health care. My contribution, Bodies of Steel, Bodies of Mush: The Hard Body and Paul Verhoeven’s Dystopian Science-Fiction Action Films, discussed how RoboCop, Total Recall and Starship Troopers all subvert Susan Jeffords’ conception of the hard-body action film. Keep reading for the transcript.

Introduction

Richard Nixon, writing in his 1980 book The Real War, raised the question of whether the United States would be a nation of ‘steel or mush’. Condemning the outgoing Carter administration particularly, and the whole US more broadly, Nixon called for leaders who are ‘”steely”, resolute and certain’ as opposed to those he called ‘”paralyzed”…, uncertain, “mushy” and wavering’[i]. The work of Susan Jeffords saw a link between the rise of what she coined the hard-body Action Film with the rise of a steelier version of American masculinity, encapsulated by the election in 1981, and re-election in 1984, of Ronald Reagan. As Jeffords states, ‘Ronald Reagan became the premiere masculine archetype for the 1980s, embodying both national and individual images of manliness that came to underline the nation’s identity during his eight years in office’[ii]. This masculinity, one which was ‘tough, aggressive, strong and domineering’[iii] counteracted the perceived weak and feminine Carter years (and Hollywood’s cinema of crisis and doubt evident during the New Wave period) and was encapsulated by the figures of Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone. This new hyperbolic masculinity, defined not only through action but through the prolonged gazing at the stars’ musculature, would place the hard-body at the centre of the 1980s box-office, establishing Stallone, Schwarzenegger (and a select few others) as among the top stars in America and around the globe.

The growing American confidence of the Reagen era was reflected in the confident and decisive actions of the hard-body Action Heroes, such as when Stallone, as John Rambo, returned to Vietnam to demonstrate the American Soldier’s superiority in Rambo: First Blood Part II (George P. Cosmatos, 1985), or when Rocky Balboa, Stallone again, put the ‘Evil Empire’ of the USSR in it’s place in Rocky IV (Sylvester Stallone, 1985). The hard-body hero is a hero of overt, muscular, physical display, ritualized suffering, and movement which became synonymous with America itself (even when represented by the heavily accented immigrant Schwarzenegger). Rooted in the freedom of the individual the hard-body hero fights not just threats foreign and domestic, but also the limits of government bureaucracy (mirroring Reagan’s Small Government policies). As Jeffords summarises, these are movies with ‘spectacular narratives about characters who stand for individualism, liberty, and a mythic heroism’[iv].

These are films that offer their spectators a sense of mastery, in terms of plot ‘in which the hard-body hero masters his surroundings, most often by defeating enemies through violent physical action; and at the level of national plot, in which the same hero defeats national enemies, again through violent physical action’[v]. Spectators vicariously experience the hero’s power through identification both on a personal level, and as a collective in that the hard-body embodies the ‘political, economic, and social philosophies’ of the Reagen era.[vi]

This paper discusses how Paul Verhoeven’s Action Science Fiction films, RoboCop (1987), Total Recall (1990) and Starship Troopers (1997) interact with, reconfigure and parody this conception of the Hard Body. The first two of these films are regularly seen as part of the Hard Body movement and I will suggest that rather than conforming to the Hard Body formula, both films explore, expose and critique the very idea of the Hard Body. The third film, made after the Reagan period and post the box office dominance of the Hard Body Action film, builds on the themes from the previous two films but goes further in exposing the hollowness of the Hard Body concept – all three films demonstrate the tenuousness of the Hard Body, but also draw attention the anxieties the Hard Body formula represses. Rather than reinforcing the hardness of the Hard Body, Verhoeven’s films remind us consistently of the mush that sits within the hard shell, that the body’s essential fragility is inescapable and that the political associations of individuality and freedom are illusory. The construction of the Hard Body is drawn attention to, and the spectator’s sense of mastery is subverted – particularly through the repetition of images and themes of lobotomy, a mushy brain.

Part One: Total Body Prosthesis.

1987’s RoboCop was Verhoeven’s first American film and it is broadly recognised as a satire on many Reaganite policies, particularly the use of the private sector over the public and consumerism more generally. Despite this, RoboCop is often taken at face value as a Hard-Body film, indeed the protagonist is seen as the ultimate Hard-Body, his armour constructed from “titanium laminated with Kevlar”, therefore being an extension of the gym, and steroid, built bodies of Stallone and Schwarzenegger (indeed the panels of RoboCop’s armour mirror the shapes of such bodies). However, while RoboCop might appear as the ultimate hard-body the film asks questions of what lies inside the body and highlights it’s clearly constructed nature.

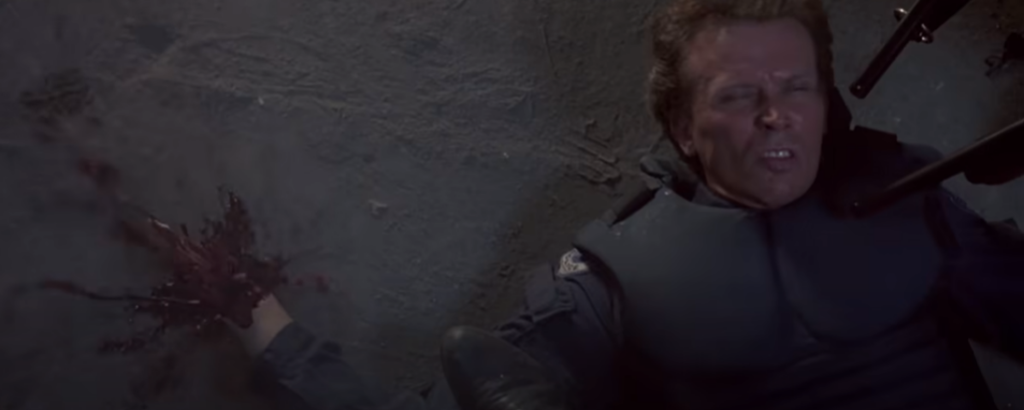

Much of RoboCop does conform to hard-body action tropes – we are given a hero who goes through a moment of ritualized suffering, only to return and defeat the various villains, therefore asserting his superior masculinity. However, Verhoeven pushes these conventions, taking them much further than the typical hard-body film. Compare a sequence in Rambo III where Rambo cleans and then cauterises a wound in his side, roughly two minutes of screen time, to Murphy’s prolonged, and detailed, dismemberment at the hands of Clarence Boddicker and his gang.

This situates Murphy’s body, more average looking than Rambo’s, as a soft body that needs to be rebuilt but the suffering of Murphy extends, perhaps throughout the whole movie. The steel works finale breaks Murphy’s now Robocop body down again, puncturing, piercing and crushing the outside – far beyond the injury of the typical hard-body hero. This is paralleled with other bodies throughout the film which are similarly broken down, revealing the soft mush inside, whether Boddiker’s spraying arterial blood or Emil’s whole body transformed into softness by toxic waste. The titanium armour succeeds in stopping bullets, but nothing can completely disavow the inevitable softness of the interior.

It is worth noting that RoboCop from the neck down is entirely a constructed product, we know this from the scene in which OCP Executive Bob Morton demands ‘total body prosthesis’ – that all remaining body material is disposed of. This asks questions then of the type of masculinity being presented, and what the spectator is being invited to identify with. In short RoboCop is a castrated corporate product.

His castration mirrors the absence of love interests in many of the Hard-Body films, but makes it literal. The essential element of masculinity, the phallus (in both the literal and symbolic sense) is absent. There are of course substitutes, the large gun RoboCop keeps in his leg for instance, or the ‘interface needle’ with which he kills crime lord Clarence Boddicker act as symbolic substitutes and confer RoboCop much of his power, but for RoboCop, unlike other Hard-Body heroes, the guns and armoured muscularity do not act as substitutes for the un-showable phallus – there is no organ to sublimate with symbolism here. Further to this loss, RoboCop, or Murphy, has lost the a key component of Reaganite policy, and traditional end-point of oedipal driven narratives, the family. Is it any wonder that, when confronted with images of his family, culminating in a curtailed sexual memory of his wife, RoboCop punches out a screen in frustration. Intriguing to that in one of the first crimes he prevents, the attempted rape of a woman by two assailants, RoboCop shoots one of them in the crotch. The hero’s castration is contrasted with the villains, who express an excessive lust (not just for women, but also drugs and violence). Verhoeven has spoken about his desire, early in the pre-production process, for Murphy and Lewis to have an affair, but later realising that ‘following American puritan standards’[vii] this wouldn’t work. This then, makes RoboCop an interesting comment on the Hard-Body hero – a body constructed (perhaps paralleling steroid use), lacking in genitals but having access to destructive phallic substitutes that connote power and strength.

This satire on the hard-body outside is paralleled by the questions of RoboCop’s identity and the question of Murphy’s ghost in the machine. During RoboCop’s recovery, having been attacked by the SWAT team, a distinctly Lacanian scene plays out. Removing his helmet for the first time, RoboCop sees Murphy’s face staring back at him – a moment that invokes the ‘mirror stage’, when the a young child comes to a moment of self-identification (which Christian Metz suggests is imitated by the cinema experience[viii]).

He then proceeds to destroy the baby-food Lewis has supplied for him, a symbolic act of growing up perhaps. The helmet remains off for the rest of the film, and when asked by OCP’s head, the patriarchally identified Old Man, for his name, he now replies ‘Murphy’. This seemingly confirms a moment of self-realization and self-identification, severing ties with the corporate product and reassertion of human individuality. But this triumphant moment is undercut in several ways – Murphy still requires the permission of the Old Man to kill Dick Jones (with the suggestive line ‘Dick, you’re fired’), his prime directives, including the classified ‘Any attempt to arrest a senior officer of OCP results in shutdown’ remains and the final cut of the film, hard-cutting from a smiling Murphy to the title card ‘RoboCop’ reasserts his nature as corporate product, suggesting that his reasserted identity is an illusion.

There is also the question of the bullet lodged in Murphy’s head, embedded in the prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain that ‘regulates thoughts, actions and emotions’[ix], and the area targeted by lobotomies. A sexless, lobotomized, corporate product – is this, perhaps, Verhoeven’s (and screenwriters Ed Neumeier and Michael Miner’s) view of the mythic heroism embodied by Stallone and Schwarzenegger? RoboCop, and through identification the spectator, have only the illusion of mastery here.

PART 2: IT’S THE LATEST THING IN TRAVEL. WE CALL IT THE EGO TRIP

The question of lobotomy is essential to Total Recall, it’s threat repeated several times to the hero Douglas Quaid. The casting of the ultimate hard-body, Arnold Schwarzenegger, as Quiad allowed Verhoeven to create a more hyperbolic film than perhaps first envisioned in the multiple script drafts. Rather than simply reiterate Schwarzenegger’s previous screen image however, Verhoeven uses the opportunity to subvert some of core elements of his star’s screen persona. Central to this are Quaid’s fantasies of Mars and desire to visit Rekall – in a sense even Arnie dreams of being Arnie and wants to take ‘a holiday from himself’. This tacitly points to the unreality of the Schwarzenegger image, that it is artificial in itself. Indeed, artificiality is a major concern of the film, whether it is in the sense of artificial memories, the predominance of screens (such as one in Quaid’s kitchen showing an artificial landscape), the Johnny Cab driver or the moment when Quaid becomes indistinguishable from his own holographic projection ‘Ha ha ha, you think this is the real Quaid…?’.

Perhaps the most subversive elements of the film is Verhoeven’s treatment of Schwarzenegger’s body which, other then an early scene, remains mostly covered by clothing. Gone are the explicit and fetishizing displays of muscularity. Instead, we have an elastic Arnold, one that cab be pulled and stretched in strange and unnatural ways. Three scenes show us this. The first is when Arnold removes the bug from his head, stretching his nose impossibly (and suggesting there was an unreasonably large gap somewhere in his head for it to be hidden), the moment when the ‘Two Weeks’ disguise pulls apart showing his head in an impossibly small space, and the finale where his eyes bulge and tongue lolls during his expulsion onto the airless Martian landscape (Quaid and Melina are marked out from Cohaagen by their ability to endure this stretching, in effect to be soft and malleable as opposed to hard and unyielding).

Of course, all these moments are performed by, very convincing, special effects, and these impossible moments return us to the questions concerning the real and fantasy that dominate the film (they also draw attention, in similar ways to how The Terminator does, to the fact there is something unreal about Schwarzenegger himself).

If the hard-body hero is made to have an elastic body here, the question of the mush inside returns in several ways. Visually it is dramatized through the mutants who populate Venusville on Mars – oxygen starvation has transformed their bodies, so that, in many cases, the barriers between internal and external have collapsed, organs breaking through their skin.

Returning to questions of fantasy and reality, we see how Verhoeven draws attention to the film’s narrative construction in the scenes where Quaid visits Rekall and the plot of the rest of the film is laid out exactly as his fantasy of being a secret agent who will ‘get the girl, kill the bad guys and save the entire planet.’ Quaid’s surrender to the fantasy mirrors the spectator’s, but it also throws doubts on our mastery of the narrative. By making the spectator conscious of the construction, then questioning its validity in the scene with Dr. Edgemar, our identification with Quaid, the spectator’s ‘Ego Trip’, is questioned and thrown into doubt. Despite this, Verhoeven allows the spectator to retain their feeling of mastery, as Quaid eventually wins, only to pull it away at the end. As Verhoeven describes regards Doug’s fate, ‘I mean he is lobotomized at the end. That’s why at the last shot, when they are so happy and kissing each other, it slowly fades to white, which to me meant “OK, there he goes. That’s the end-that’s the dream – they lobotomized him”’[x].

The archetypal hard-body hero, reconfigured as an elastic body – but elastic only through fantasy. Meanwhile he lies on a table somewhere, his brain turned to mush.

Part 3: They Sucked his Brains Out

Starship Troopers’ Johnny Rico is Verhoeven’s final critique of the hard-body hero – the individualist, muscled, American reduced to a simpleton unable to make decisions. As Verhoeven described it, the characters of Starship Troopers are ‘streamlined in a certain way… you could also call it lobotomised’.[xi] In the fascist future the film depicts even South Americans are reduced to being the corporate ideal of the bland US soap opera star; Rico, on the surface at least, appears to fulfil Jefford’s formula. He undergoes extreme suffering (the flogging which, like Murphy’s death in RoboCop, resembles the Crucifixion),

he possesses the muscular body that suggests mythic heroism, and moves through a series of action scenes. However, Rico never suggests any of the individuality Jeffords suggests, or that was part of the Reaganite messaging. Rather he is a character devoid of individual drive, manipulated by others, and incapable of making decisions.

Rico’s actions during the film are responses to others, rather than from a drive of his own. He decides to enlist (partly due to his teacher Rasczak, partly peer pressure) then changes his mind after his parents promise him a holiday, then changes his mind again (Carmen being a big influence), only to decide to leave the Mobile Infantry when Carmen dumps him, via a videoed Dear John letter. Despite gaining swift promotion in the field, there is little to suggest Rico has great leadership skills – rather he simply has a great capacity for surviving. He orders another trainee to remove their helmet during a live-fire exercise, which leads to the trainee’s death, and later he is guided to find the surviving Carmen, unknowingly, by his psychic friend Carl suggesting he has the mental ability similar to Carl’s pet ferret (who was similarly manipulated in an earlier scene). It is perhaps no wonder that a Brain Bug never threatens Rico – it is unlikely it would find much to suck out. But of course, the sucking out of brains by the Bug mirrors the sucking out of brains by the fascist society. As Rico gets promoted we watch as he simply adopts the persona of his teacher/commander Rasczak, imitating his dialogue and behaviours. Here the hard-body ideal is rendered brainless, lobotomized by society rather than a bullet or a Leucotome – Verhoeven himself stated ‘I felt that the soldier characters were all idiots. They were all willing to die… because of the propaganda they had been fed.’[xii]

And the film offers us a parallel hard-body, that of the bugs – in many ways harder-bodied than the humans and their armour which appears to offer little to no protection from attack. Indeed, the film is consistently reminding us of the fragility of the human body, from the various characters showing amputations and prosthetics, to the many violent ways in which the bugs kills the humans (including various bisections and decapitations). Rico himself is believed dead for a time after his leg is pierced through by an Arachnid. The bugs however are still fragile, and the film shows us the many ways in which they can also be reduced to the mush inside the hard carapace. One early scene, set at high school, shows the various organs of one bug and Rico’s takedown of the Tanker Bug throws orange goo up into his face. The only soft Bug, provocatively, is the Brain Bug – a soft mass that ripples and undulates. Is it significant too that the highly intelligent, and psychic, Carl is one of the few characters not to be defined by muscularity and physical action?

The mushy fragility of human life is always present – no amount of hardening (in literal muscularity or metaphorical political philosophies) can hide that fact. What then of mastery, as Rico shows such little of this quality (in some ways the real hero of the film is Drill Sargeant Zim who captures the Brain Bug). Whereas the two previous films were subtler in subverting the hard-body ideal, Starship Troopers is more direct by suggesting the very ideal is empty, individuality a myth in this ultra-right wing society.

Part 4: Consider this a Divorce.

Robin Wood, in discussing the Horror film from the 1960s to 1970s, suggests the following:

Two elementary Freudian Theses: in a civilization founded on monogamy and the family, there will be an immense, hence very dangerous, surplus of sexual energy that will have to be repressed; what is repressed must always struggle to return, in however disguised and distorted form.[xiii]

For Wood the horror film brings forth, through analogy, that which is repressed. During the Reagan administration there was an emphasis on the return to traditional family values[xiv], with several action films of the era (such as the Lethal Weapon films and Die Hard) reflecting this concern. More generally the hard-body film is one that largely represses sex, with very few sexual relationships for the heroes. Verhoeven’s three films have great fun in unpicking this, by bringing forth the sort of psychosexual imagery usually sublimated or disavowed in such films – except, perhaps, when displaced into muscles and weaponry. Castration imagery recurs, not only in Robocop where it is quite literal, as we’ve discussed, but in Total Recall through Lori’s crotch based attempts to subdue Quaid, to the amputation of Richter’s arms. Various limb removals in Starship Troopers reflect this too. Other, more explicit and challenging, psychosexual images are also in play: the quasi-male-birth of Quato out of George’s body, the killing of Benny via drill and the typical Arnie quip ‘Screw You’; the Martian pyramid reactor can be seen as a feminine space of caverns, that gives out a life saving ejaculation of air at the film’s climax; the Phallic Spaceships of the Federation are assaulted by semen like spays of plasma; Rico’s vaginal leg wound is healed in an amniotic tank; more caverns appear in Starship Troopers and the Brain Bug itself, is a nightmare blend of vaginal orifice and penetrating, sucking, appendage (which we only see attack men).

Marriage, one of the core elements of the Reaganite revival, tied to his support from the Evangelical Christian Right, is subverted too – a ‘lost paradise’ for Murphy to which he cannot return, a burden for Quaid that limits him from indulging in his fantasy (and easily dispatched with the one-liner, ‘Consider this a divorce’), and it is not even on the cards in Starship Troopers, where Carmen happily moves between men as her career progresses, men and women shower together without a hint of sex and Rico fails to retain a romantic partner.

This use of psychosexual imagery and subversion of marriage is, I would suggest, part of Verhoeven’s critique of what he sees as the ‘puritan attitude in America’ – bringing forth the desires and ideas that such as an attitude must repress.

Conclusion

In conclusion, these three films take the hard-body concept and subvert and play with it – the body is deconstructed, wounded and lobotomized. The individuality the hard-body was supposed to connote is withdrawn, and with it a complete sense of mastery for the spectator, either personal or collective.

In RoboCop Verhoeven shows the hard-body as a corporate construct, the hero’s return to individuality undermined by his persistent programming. In Total Recall the ultimate hard-body star, Arnold Schwarzenegger, is made elastic before a final lobotomy curtails the fantasy of being Arnold Schwarzenegger. And in Starship Troopers, perhaps the most thorough critique, the hard-body hero is the idiot soldier of a fascist republic, incapable of individual thought. Hard bodied perhaps, but mushy brained.

Bibliography

Arnsten A.F. (2009) Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nat Rev Neurosci. Jun;10(6):410-22. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2907136/#:~:text=The%20prefrontal%20cortex%20(PFC)%E2%80%94,detrimental%20effects%20of%20stress%20exposure. [accessed 03 September 2023].

Ayres, Drew (2008). Bodies, Bullets, and Bad Guys: Elements of the Hard Body Film. Film Criticism. 32 (3), 41-67.

Cornea, Christine (2007). Science Fiction Cinema: Between Fantasy and Reality. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Ellis, John (1994). Visible Fictions: Cinema, Television, Video. London: Routledge.

Glass, Fred (1990). Totally Recalling Arnold: Sex and Violence in the New Bad Future. Film Quarterly, 44 (1), pp. 2-13.

Jeffords, Susan (1993). Can Masculinity be Terminated?, in Cohan, S. & Hark, I.R. (eds.). Screening the Male: Exploring Masculinities in Hollywood Cinema. London: Routledge, pp. 245-262.

Jeffords, Susan (1994). Hard Bodies: Hollywood Masculinity in the Reagan Era. Rutgers University Press: New Jersey.

Kac-Vergne, Marianne (2018). Masculinity in Contemporary Science Fiction Cinema: Cyborgs, Troopers and other Men of the Future. London: I.B. Taurus.

Keesey, Douglas (2005). Paul Verhoeven. Cologne: Taschen.

LaBruce, Bruce (2003). Paul Verhoeven. In (ed) Barton-Fumo, M. (2016) Paul Verhoeven: Interviews. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Lebeau, Vicky (2019). Psychoanalysis and Cinema: The Play of Shadows. Columbia University Press: New York

O’Brien, Harvey (2012). Action Movies: The Cinema of Striking Back. Wallflower Press: New York.

Ryan, Michael & Kellner, Douglas (1990). Camera Politica: The Politics and Ideology of Contemporary Hollywood Film. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Shea, C. & Jennings, W. (1992) Paul Verhoeven: An Interview. In (ed) Barton-Fumo, M. (2016) Paul Verhoeven: Interviews. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Tasker, Yvonne (1993). Spectacular Bodies: Gender, Genre and the Action Cinema. London: Routledge.

Telotte, J.P. (2001). Verhoeven, and the Problem of the Real: “Starship Troopers”. Literature/Film Quarterly. 29 (3), pp. 196-202.

van Scheers, Rob (1998). Paul Verhoeven. London: Faber & Faber.

[i] Jeffords (1994) 8-9.

[ii] Jeffords (1994) 11.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Jeffords (1994) 16.

[v] Ibid 28.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Cornea (2007) 136.

[viii] Fuery (2000) 15.

[ix] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2907136/#:~:text=The%20prefrontal%20cortex%20(PFC)%E2%80%94,detrimental%20effects%20of%20stress%20exposure.

[x] Shea & Jennings (1992), in Barton-Fumo (ed) (2016), 75.

[xi] Cornea (2007) 172.

[xii] LaBruce (2003) 154.

[xiii] Wood (2018) 57.

[xiv] Jeffords (1994) 191.

I had the great pleasure of chatting all things Vigilante Thriller with Dr James Newton, a lecturer in Media Studies, and a filmmaker, at The University of Kent (and author of the very good The Mad Max Effect). Check it out here

Today sees the release of The Vigilante Thriller: Violence, Spectatorship and Identification in American Cinema, 1970-76 from Bloomsbury Academic.

This is a detailed examination of vigilantism in 1970s American film, from its humble niche beginnings as a response to relaxing censorship laws to its growth into a unique subgenre of its own. Cary Edwards explores the contextual factors leading to this new cycle of films ranging from Joe (1970) and The French Connection (1971) to Dirty Harry (1971)and Taxi Driver (1976), all of which have been challenged by contemporary critics for their gratuitous, copycat-inspiring violence. Yet close analysis of these films reveals a recurring focus on the emerging moral panic of the 1970s, a problematisation of Law and Order’s role in contemporary society, and an increasing awareness of the impossibility of American myths of identity.

There’s a book on the way… The Vigilante Thriller: Violence, Spectatorship and Identification in American Cinema, 1970-76 from Bloomsbury Academic is available for pre-order now for release on 21st April 2022.

Exploring the cycle of Vigilante films that occurred in the 1970s, The Vigilante Thriller explores the socio-political and cinematic backgrounds of the films (including Dirty Harry, Death Wish and Taxi Driver) before analysing the spectator’s relationship to these transgressive texts.

A few years ago I had the pleasure of speaking at the American New Wave: A Retrospective conference at Bangor University organised by Greg Frame and Nathan Abrams. After the conference finished a call went up for contributions developed from the papers and lo and behold the time is coming when this work will be released. Due to be published on 21st October 2021 by Bloomsbury Academic, New Wave, New Hollywood: Reassessment, Recovery and Legacy collects a series of essays that hope to re-evaluate some of the key ideas and theories that dominate our views on the period and includes my thoughts in Chapter 3 ‘Formal Radicalism vs. Radical Representation: Reassessing The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971) and Dirty Harry (Don Siegel, 1971)’. It’s a bit intimidating to be in such esteemed company, and not to mention rather exciting, but I’m sure I’ll keep my feet on the ground – as Harry Callahan reminds us, ‘A man’s got to know his limitations’.

NB: thanks to Simon Brew of Film Stories magazine for forwarding the link to watch a preview copy of this doc.

I first saw The Exorcist in a cinema during a Halloween showing in 1998 the same year Mark Kermode’s documentary first appeared. The film was still unavailable for home viewing back then, a status conferred during the 1980s when the Video Nasty moral panic was in full swing, and by 98 it had gained its full status as the ultimate horror film, one that had people running from cinemas back in 1973 when first released. It was with much excitement and trepidation that I approached the screening that night. I’d love to say that my experience mirrored those seen in 1973, but sadly the packed crowd in Theatr Gwynedd struggled to take the film seriously (myself included). When Regan vomited, we laughed.

For many years the appeal of the film eluded me until I started teaching a module on Shocking Cinema. I decided to revisit it, analysing it in detail and discussing with learners the original hysterical reactions the film provoked. This was, after all, a film condemned as evil by Billy Graham and one that pushed moral campaigners like Mary Whitehouse to fervent levels of apoplexy. There must have been something about it; when it was shown in Birmingham a Christian group went so far as to distribute leaflets to film-goers with a helpline for discussing the film’s issues.

Time has certainly withered it’s shock value but I have come to appreciate it, particularly as a drama about faith with Father Karras, played with great sensitivity by Jason Miller, at it’s centre. The more I see the film the more I admire its pacing, design, use of sound and imagery. It may not scare me, but I can enjoy it. I am, in my own odd way, a fan of The Exorcist.

Kermode, on the other hand, has long shared his love for the film, a love born from watching its trailer as a terrified 11 year old. The Fear of God is his tribute, a making of documentary that’s done the rounds since 1998 but has never been widely seen in its full form (except at film festivals) until now, released on the BBC iplayer this Halloween. It’s a thorough and entertaining look back at the film’s production and a shockingly young Kermode pops up now and then to link the various elements from writer William Peter Blatty’s inspiration to the scenes of audience emerging terrified from cinemas. Mostly the documentary lets the cast and crew speak for themselves, their talking heads intercut with behind the scenes footage and some alternate takes (some of which have been subsequently included in re-releases of The Exorcist on DVD).

There’s some great information included, although much has lost it’s novelty since 1998 as the internet has allowed such facts to be dispersed to hungry fans more easily. Some good fun can be had at the thought of alternative history versions threatened during production – imagine the film starring Jane Fonda and Paul Newman – and the sections on practical effects and sound mixing remind us of how ground-breaking the film was. Today we’re saturated with supernatural horror and exorcism films; it’s fun to step back to a time when such things were pushing the envelope, all on a major studio’s dime. The film was one hell of a risk for Warner Bros, but one that paid off handsomely.

All the principal cast appear and recount their experiences, including their views of the fabled “curse” that supposedly dogged the set. Most buy in, only the dry witted Max von Sydow dismissing such ideas (in part due to his Swedish Protestant upbringing, where the devil was a figure of fun). In some ways it’s quite surprising to see how deeply some of them accept the idea that evil is somehow present in the film – it’s certainly marked Friedkin who’s since gone on to make the documentary The Devil and Father Amorth about a real Vatican exorcist.

As these documentaries go The Fear of God is exemplary and to discuss in too much detail would render it moot – so go watch it. Before you do though I would like to discuss one aspect of Kermode’s film I found more disturbing than The Exorcist itself, and that’s director William Friedkin.

Friedkin’s star was on the rise in 1973, having brought multiple Oscar winner The French Connection to the screen in 1971. His background in documentary gives both The French Connection and The Exorcist a grounding in reality which was new to their genres and the latter film represents a high point in his career (some of his later films, such as Sorcerer and Cruising are important, although none would come close to the impact of The Exorcist) and he stands as a director of note during the New Hollywood period. But some disclosures during the documentary give me pause and ask questions not just of Friedkin but of the auteur led approach to cinema prevalent during the 70s. Although mostly recounted with smiles, stories of Friedkin firing guns on set to shock actors, slapping another in the face and having his star Ellen Burstyn yanked across a set for one effect (causing her injury) suggest a level of control and recklessness that borders on abuse. It reminds of Kubrick’s direction of Shelley Duvall on The Shining or Maria Schneider’s treatment on the set of Last Tango in Paris. The Exorcist is often read as a treatise on male power – the Catholic Church as a symbol of male authority fighting with the devil over a young girl’s body – but in it’s production we find a real example of this power in action. When Friedkin nods to his special effects guy to pull Burstyn at full force, against her wishes, her safety is ditched for the shot, her consent never asked for. She may laugh about it now, as she does here, but behind the smile there is clear anger. It’s little wonder she calls Friedkin a “maniac”. Some will argue that it was worth it for the film, that we’re too sensitive now, etc. Maybe. But if you hire a priest to be in a film don’t be surprised when he struggles to get into the emotionality of a scene. One answer would be to slap him. Another would be to hire an actor instead. These are little glimpses into a version of the film’s production that’s less glowingly recounted, more problematic and it’s a bit of a shame we don’t get to know more – but this is a documentary as act of love for a film, not an exploration of its director.

46 years after it’s first release, and 21 years since I first saw it, The Exorcist still doesn’t scare me, but I think working with William Friedkin would.

Full disclosure: Cobra is not a good or interesting film in any of the traditional ways. It lacks narrative coherence, the story is bare to non-existent, and the performances are largely one-note. It is, however, a film that allows us to explore how the audience can be employed in the creation of meaning. In fact I’d go as far to suggest that the audience really makes the film themselves due to it being thoroughly disjointed. In effect, the spectator becomes the main agent of meaning culling from their own understanding of genre, narrative and various intertexts in an act of creative spectatorship. In this Cobra emerges as a key action text of the 1980s, telling us just how tuned into the genre action fans were.

To say that Cobra was critically unloved on its release would be something of an understatement. Nina Darnton, in The New York Times, suggested that the film was “disturbing for the violence it portrays” and showed “contempt for the most basic American values embodied in the concept of fair trial”. Sheila Benson, in the Los Angeles Times, cited the films “pretentious emptiness, its dumbness, it’s two-faced morality”. David Denby went even further titling his New York Magazine review “Poison”, and comparing Cobra to Dirty Harry (Don Siegel, 1971), citing the former’s lack of “the peculiar sad gravity that Clint Eastwood gave him.” None of this seemed to harm Cobra’s box office, with it gaining $49 million in the US alone (ww.boxofficemojo.com), and totalling $160 million worldwide (Fisher, 2016), helping to continue Stallone’s profitable run at the box-office (although it did show a significant drop from the less explicitly violent Rocky and Rambo films).

Revisiting the film now, one wonders why the reviewers were so worried as it’s such a disjointed and unbelievable film that its clearly addresses its audience in a self-conscious post-modern and shallow manner, to the point where it becomes sort of sub-Brechtian in its emptiness (although politically it’s about as far from Brecht as you can get in its continual celebration, and destruction, of consumer products). The critical comparisons to Dirty Harry are revealing as it’s in this that Cobra starts to come alive as a film, drawing much of it’s meaning from the earlier film series (it’s also notable that Dirty Harry was decried in similar ways on release). The opening of the film directly imitates the second Dirty Harry film, Magnum Force (Ted Post, 1973), both culminating in the hero’s gun firing out of the screen at the audience (immediately breaking the fourth wall and puncturing any claims to an immersive experience). The conflict between Cobretti (Stallone) and his superiors is lifted almost directly from the Dirty Harry films, but is subverted somewhat by the casting of Andrew Robinson who played the Scorpio Killer in Dirty Harry.

Here, as Detective Monte, he continually challenges Cobretti – suggesting that the audience, upon recognition of Robinson’s distinctive face and voice should conclude that if that psycho thinks Cobretti is too violent, he must be heavier than Harry Callahan. Casting Reni Santini as Cobretti’s partner is a direct call-back to the almost identical role he played in Dirty Harry, both characters even being called Gonzales (the only discernible difference in the performances is a hat). The film sutures together the plots of the Dirty Harry films (excluding The Dead Pool, released in 1988) – the psychotic killer of Dirty Harry (now The Night Stalker), the fascist group from Magnum Force merges with the terrorist group of The Enforcer (James Fargo, 1976), with elements of the romantic relationship in Sudden Impact (the character of the turncoat cop Stalk in Cobra also looks very similar to unpleasant butch-lesbian stereotype Ray in Sudden Impact (Clint Eastwood, 1983)). At this point the film is directly drawing from these films in a very knowing manner, clearly assuming that the audience knows the other texts – this knowledge functions as a series of narrative and characterisation short cuts. Exposition is barely required as the audience is already aware of how this narrative will play out – the opening action scene, in a grocery store, imitates similar Dirty Harry scenes, without requiring any sense of location or time – it is enough that a crime has occurred. Ritualistically we expect Cobretti to arrive and solve the problem, which he duly does, so no suspense or tension is created or necessary. It becomes a scene entirely designed to showcase how much dirtier Cobretti is than Harry (Cobretti wears his mirrored shades all the way through the scene; he pauses to sip from a Coors; his killer also has a bomb; he has his own catchphrase “You’re the disease, I’m the cure.”) Thus, the film works on a ritualistic and generic level, playing out exactly as expected in some ways, despite some particularly curious directional choices we’ll come to.

On an intertextual level it’s also worth discussing how the films’ studio backing primes the audience for the content. As both a product of The Cannon Group and Warner Brothers (as distributor) the studio logos that start the film suggest an uneasy nexus point between one studio known for cheap exploitation/action pictures and another with a rich history but also, during the 1980s, a skewing towards action films (Warner’s would in 1988, after all, give the world the dubious gift of Steven Seagal). Of course, the Warner link pulls straight back to Dirty Harry, whereas the Cannon group evokes the world of Charles Bronson and Chuck Norris and ultra-violent fayre like The Exterminator II (Mark Buntzman, 1984). Given the strength of the growing home-video market Cannon had become well-known, if not infamous, to audiences but the Warner Bros. logo gives the film a sheen of quality (original trailers trade on the Warner logo more than the Cannon connection). It’s also one of the first 80s action films to be set at Christmas, beating Lethal Weapon and Die Hard to the punch. Not that the Christmas setting has much purpose, other than occasional pans over nativity scenes or Christmas trees incongruous to the sunny LA setting, perhaps left over from the previous years Cannon action ‘epic’ Invasion USA (Joseph Zito, 1985).

The opening narration sets the tone for the film, but also a premise from which the subsequent action is contextualised to make sense;

In America, there’s a burglary every 11 seconds, an armed robbery every 65 seconds, a violent crime every 25 seconds, a murder every 24 minutes and 250 rapes a day.

With this, delivered in Stallone’s familiar drawl, the justification of all the violence that subsequently occurs is drawn (ironically Cobretti kills way more people than The Night Stalker manages). It’s worth noting that during 1986 there was an upswing in homicide (Wilkerson, 1987) but also that Cobra draws no attention to causes – the film exists in a Manichean universe in which archetypes, far removed from reality, battle each other.

After the voice-over opening and before the grocery store action sequence the first of several montages plays out which are directed in an almost surreal manner, bearing more comparison to the work of Eisenstein in the juxtaposition of images than in a typical Stallone/Rocky training sequence. These contextless disconnected images of men clashing axes together, tattoos, graffiti and a motorbike are intercut rapidly giving the audience all the introduction to the films far-right group they’ll ever get or need (their politics almost subliminally suggested through their skull and axe logo). But of course, the audience needs no more introduction, it’s enough that these people exist to be opposed. A second montage, in which both Cobretti and The Night Stalker search for murder witness Ingrid (Brigitte Nielsen), set to Robert Tepper’s Angel of the City, cuts between protagonist and antagonist and Ingrid during a bizarre fashion shoot in which she drapes herself around various robotic creations – it introduces some almost avant-garde imagery into proceedings for no discernible purpose. Ingrid’s career, as a model, indicates her purpose in the film – beautiful object, nothing more.

From here the film proceeds much as one would expect, and yet lacks many of the elements of character and dialogue any competently made Hollywood movie would have. Much of this relates to the disputed direction of the film, with some claiming that Stallone directed the film himself (when he wasn’t busy off set consummating his recent marriage to Nielsen). He certainly wrote the film (as much as it has a script) ditching any part of the novel Fair Game by Paula Gosling on which it is nominally based. It also has a troubled post-production with numerous cuts being made to secure an R-rating and to increase showings, removing around 30 minutes of material. Although this editing creates numerous continuity errors it plays into the audience’s ownership of the narrative, making them work to film in the gaps and the cuts remove the superfluous elements that the audience knows anyway.

And then there’s the hero, Stallone’s Marion Cobretti first-named, one assumes, in tribute to John Wayne (at one-point Stallone spins his semi-automatic Colt, with cobra picture on the grip, round his finger despite the fact this would, in all likelihood, result in him shooting himself). Even by Stallone’s standards his performance is low key, a sleepy re-tread of previous performances marked only by his continued wearing of gloves and innovative way of eating pizza (watch it, it’s very odd).

Cobra exists purely as a series of attitudes, instead of a performance per se. The romance, between Cobra and key witness Ingrid), is particularly pallid but is part of where the film extends out from film and into Stallone’s real life – the fact that they were married in real life creates the sense that they’re a couple, so small details such as chemistry or interplay are moot. Similarly, the serial killing, far-right leaning, villain is played by Brian Thompson who bears a resemblance to Stallone’s great box-office rival Arnold Schwarzenegger (who himself was, for a time, dogged by rumours of far-right leanings and an admiration for Hitler (Left, 2003)). Again, the lack of characterisation is subverted through the casting, reaching into Stallone’s own life and rivalries as a short-cut.

Scratch away at Cobra and one finds various palimpsests – the Dirty Harry films, Stallone’s own life and career, the Cannon imprint – and these are essential for understanding the film’s popularity. On its own it’s an incoherent piece, but as an intertextual construction it starts to make a certain amount of sense. It is Stallone’s life and career up to that point culminating on screen, taking aim at one of his direct progenitors while jabbing at the current competition. It remains, in most respects, quite a bad film but it’s one that highlights how the audience can be engaged beyond the text itself to create narrative and meaning – it’s a film that operates in the audience’s understanding of narrative and archetypes, allowing such niceties as character and plot development to be dismissed.

Darnton, Nina (1986) Film: Sylvester Stallone as Policeman, in Cobra. The New York Times. May 24.

Benson, Sheila (1986) Move Review: The ‘Cobra’ That Saves L.a. Los Angeles Times. May 24.

Denby, David (1986) Poison. New York Magazine. June 9.

http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=cobra.htm [accessed 13/0618]

Fisher, Kieran (2016) Cobra at 30: saluting a Stallone action treat. [online] http://www.denofgeek.com/uk/moviescobra/40861/cobra-at-30-saluting-a-stallone-80s-action-treat [accessed 13/06/18]

Wilkerson, Isabel (1987) URBAN HOMICIDE RATES IN U.S. UP SHARPLY IN 1986. The New York Times [online] https://www.nytimes.com/1987/01/15/us/urban-homicide-rates-in-us-up-sharply-in-1986.html [accessed 15/06/18]

Left, Sarah (2003) Arnie Denies Admiring Hitler. The Guardian. 3 October. [online]. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2003/oct/03/usa.sarahleft [accessed 14/06/18]

There’s a bad old joke that goes somewhat as follows:

A Native American chief is tasked with buying toilet roll for his village – he goes to the local store and asks for the options.

“Well, there are three options,” says the clerk. “White Cloud, Cotton Mist and Economy.”

“How much is White Cloud”, asks the Chief, “That sounds like a good toilet paper”.

“2 dollars a roll”.

“That’s too much for the whole village, what about Cotton Mist?”

“1 dollar a roll.”

“Still too much! What about economy?”

“50 cents a roll.”

“Ok, but why does it not have a nice name, why is it just economy?”

“It just is, it’s too basic to have a name.”Several weeks pass until the Chief returns to the store to re-stock. He approaches the Clerk. “I have a name for your economy roll” he says.

“Ok” replies the Clerk, “What is it?”

“John Wayne.”

“John Wayne? Why?” “Because it’s tough strong and don’t take no shit off no Indian…”

Like I said, it’s not a good joke but it does point to the place of John Wayne in American cinematic mythology and, especially, in the representation of masculinity. For many years Wayne’s stoic image dominated the Western and the War Movie, progenitors of the modern action film. It’s an image I watched on a TV as a child, in the endless re-runs of old movies back when there were only four channels in the UK. We played Cowboys and Indians in the playground with no sense of the historical truth behind the images that played across the tube. The heroics seemed simple and accessible; moving up to the films of Schwarzenegger and Stallone wasn’t difficult. The settings had changed, but the simple morality seemed the same. There were good guys and bad guys and the good guys won because they were better in every sense.

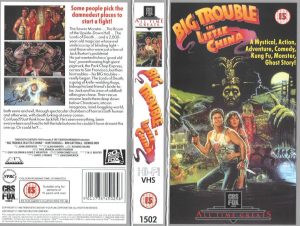

And then came Big Trouble in Little China. It sure looked from the VHS cover like a typical film. There was Kurt Russell, all muscles, gun held aloft as Kim Cattrall lay seductively at his feet. So, the Chinese theme seemed a little different but, like swapping Native Americans for Latin American drug dealers in so many other films, the ethnicity of the bad guys never really mattered (as long as they were thoroughly Othered from the hero). The black tape was pushed into the VHS player, the familiar click and whirr followed by the fuzzy lines on the TV. And then… something completely different unfolded. I loved it then and love it now, although at the age of 10 I barely understood how clever John Carpenter’s film is at undermining the typical conventions of the American hero.

On release Big Trouble was not a success, despite some strong reviews. Both Carpenter and Russell point to company politics undermining the film: the producers wanted something closer to Raiders of the Lost Ark (Steven Spielberg, 1981) and were unhappy with the jokey tone; the release was undermined by a last minute and poorly thought out marketing campaign which suggested a traditional heroic narrative, with a traditional hero (including lobby cards asking “Who is Jack Burton” above images of Russell who was yet to be confirmed as an above the title star).

Ironically the film had begun life as a Western, albeit one mixed with supernatural Kung-Fu elements, until Carpenter, and writer W.D. Richter, retooled it for the modern day. Ditching the Old West setting was designed to make the film more accessible, but only serves to play up its weirdness. The audience is asked to believe that within modern day San Francisco there is not only a Chinatown (reasonable), dominated by warring Kung-Fu gangs (a bit less credible), where Chinese mysticism is an everyday occurrence (now we’re getting odd) and below the street is a network of tunnels where the “black blood of the earth” flows (that’ll be bonkers, then). Stir in a near immortal villain (James Hong’s David Lo Pan) who needs to marry a girl with green-eyes to regain his flesh, so he can then conquer the universe, three Kung-Fu masters with powers based on the weather and a red-haired monster and it starts to become clear just how odd this is for a studio produced film. Also, did I mention the flying eyeball?

All of this spectacle was entrancing to my ten-year-old eyes – it was my first Kung-Fu movie and helped inculcate a delight in the genre that remains today. But as an adult what stands out is Russell’s performance as nominal hero Jack Burton. Through the movie Russell’s performance, and Carpenter’s direction, deconstruct the myth of the American hero, turning Burton into, what Carpenter later described in a DVD extra, as

“John Wayne without a clue.”

A prologue, filmed at the studio’s behest after they became nervous of Russell’s performance, only serves to build up his character, making the reality even funnier. Chinese mystic Egg Shen (Victor Wong) tells a lawyer that the world “owes a debt of gratitude to Jack Burton”, before we cut straight to Burton’s truck in which he, between mouthfuls of sandwich, speaks ridiculous platitudes to his CB radio:

A prologue, filmed at the studio’s behest after they became nervous of Russell’s performance, only serves to build up his character, making the reality even funnier. Chinese mystic Egg Shen (Victor Wong) tells a lawyer that the world “owes a debt of gratitude to Jack Burton”, before we cut straight to Burton’s truck in which he, between mouthfuls of sandwich, speaks ridiculous platitudes to his CB radio:

When some wild-eyed, eight-foot-tall maniac grabs your neck, taps the back of your favourite head up against the barroom wall, and he looks you crooked in the eye and he asks you if ya paid your dues, you just stare that big sucker right back in the eye, and you remember what ol’ Jack Burton always says at a time like that:“Have ya paid your dues, Jack?” “Yessir, the check is in the mail.”

Burton looks like the hero but the dark glasses he wears while driving at night and in the rain point to his lack of understanding; this is a man literally driving blind, which he remains throughout the story. His appearance is further undermined by the ridiculously high legged boots he wears throughout.

As the film progresses it becomes evident that the man who’s supposed to carry the film is actually the sidekick, with Dennis Dunn’s Wang Chi emerging as the film’s real hero (he even wears a hat that looks very similar to Indiana Jones’ fedora). Burton  is a bull-shitting protagonist with no idea what’s going on, blundering into an Asian culture and presuming that everyone there will simply bow down to him and his bluster (shades of Vietnam?). Wang is his friend and allows Burton to tag along in attempts to rescue Wang’s betrothed Miao Yin (Suzee Pai) but it’s extraordinary how useless Burton is, and how little he realises it. Indeed, it’s his posturing at the airport that creates the sequence of events that lead to Miao Yin’s kidnapping – if he hadn’t gone with Wang perhaps none of this would have occurred…

is a bull-shitting protagonist with no idea what’s going on, blundering into an Asian culture and presuming that everyone there will simply bow down to him and his bluster (shades of Vietnam?). Wang is his friend and allows Burton to tag along in attempts to rescue Wang’s betrothed Miao Yin (Suzee Pai) but it’s extraordinary how useless Burton is, and how little he realises it. Indeed, it’s his posturing at the airport that creates the sequence of events that lead to Miao Yin’s kidnapping – if he hadn’t gone with Wang perhaps none of this would have occurred…

As the film develops Burton’s ignorance and borderline racist attitudes are constantly undermined and exposed. He insists on calling people’s head-bands “Turbans” and his ignorance of Chinese culture and tradition expose him, as opposed to a more typical action film in which the hero would happily ride roughshod over the locals (who, a lá John Wayne’s The Green Berets (John Wayne, 1968), would be so happy for the American to help). Burton is captured, beaten up and, in one glorious comic moment, manages to miss most of the final battle-royale by knocking himself out following his own macho posturing. All he really has to offer is bluster while Wang and Egg Shen go about defeating the forces of evil. Despite the physical image that Russell casts in the marketing he can barely operate a gun and is visibly shaken when he first kills someone. When, disguised in plaid jacket and glasses, Burton attempts to gain information by visiting a brothel he’s shown to be fairly useless there too, undermining the heterosexual vitality that is a given of most movie heroes. Of course, he still gets the requisite romance, but even that doesn’t run to expectation.

Maybe the film’s real secret is that it’s not just an action film or a mystical Kung-Fu epic, it’s also a screwball comedy. It’s well-known that Carpenter is a fan of Howard Hawks (Assault on Precinct 13 (1976) riffs directly on Rio Bravo (1959)) but it’s Bringing Up Baby (1938) and His Girl Friday (1940) that are the more pertinent influences here as Burton and Cattrall’s Gracie Law snap at each other throughout, with Cattrall usually gaining the upper hand. Their romance further defuses Burton’s machismo, no more so than when he faces Lo Pan smeared in lip-stick from a recent kiss. His final rejection of her speaks to the risks of a relationship in which he would no longer be able to buy his own bull-shit; the strong woman must be avoided because she’ll keep bringing him back down to earth.

On release some claimed the film to a be an exercise in stereotypes, Roger Ebert making comparisons to Charlie Chan and Fu Manchu. Big Trouble in Little China certainly has its issues, but I think those comparisons are unfair. The film was made with a reverence for 1970s Kung-Fu movies, like Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain, and makes few concessions to the American relocation or present-day setting. Clichés are employed, but in a knowing way. Compare it to the Eddie Murphy vehicle The Golden Child released in the same year (also casting James Hong and Victor Wong in supporting roles) in which the Chinese characters are side-lined and the main love interest, of supposedly Tibetan descent, is played by an actress of English, Irish, Chilean and Iranian ethnicity.

Of course, Big Trouble’s big trick is the inversion of the usual Hollywood power relationships, with the white American male rendered impotent throughout, as opposed to, for example, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom which, two years earlier in 1984, reinforced all the old stereotypes about white heroes helping the locals who can’t help themselves. Watch the two back to back and you can notice how Carpenter and Russell undermine many of the clichés that Spielberg embraced (Ebert, by the way, gave Temple of Doom five stars and neglected to question its representations). One suspects that if Jack Burton had never turned up in Chinatown the narrative would resolve quite happily without him, as the Chinese characters are shown to be knowledgeable and capable throughout. That some people complained that Burton wasn’t much of a hero managed both to get the point and miss it completely.

The ending of the film imitates Wayne’s greatest Western The Searchers (John Ford, 1956). The hero leaves society behind knowing he’ll never fit in. But whereas Wayne departs a mythic figure held in silhouette against the never-ending backdrop of the Old West, Burton turns back and shows a brief flicker of recognition, a moment of self-reflection announcing that it’s because “sooner or later I rub everybody up the wrong way” that he can’t make common cause with Gracie. For a moment a human face replaces the smirking bravado, but it’s soon gone and then he’s back in the truck espousing bullshit.

Like so many of Carpenter’s films, a mainstream audience initially eschewed the film only for it to find a large cult following. But it deserves more than that, it deserves to be recognised as an innovative film splicing together disparate genres and having the courage to satirise its own, supposed, hero. From a decade of by the numbers action films Big Trouble in Little China stands out as something truly different. After 30 years the film still offers the same delight, but I now realise how smart the film always was. It takes direct aim at the idea of the white saviour taming the uncivilised savages and exposes him as an ignorant boor well out of his depth. Even more perhaps, it suggests that he might not even be needed.

Ebert, Roger (1984) Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. RogerEbert.com [online] Available from https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/indiana-jones-and-the-temple-of-doom-1984 [accessed 27 September 2018]

Ebert, Roger (1986) Big Trouble in Little China. RogerEbert.com [online] Available from https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/big-trouble-in-little-china-1986 [accessed 27 September 2018]